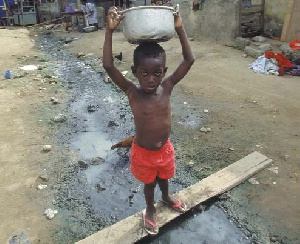

All over Ghana's capital city Accra you see people carrying water.

Children drag yellow plastic jerry cans. Young men shoulder old paint tins.

But above all the job falls to women, walking long distances, with huge metal bowls balanced deftly on their heads.

They are collecting water from roadside pumps and tanks because the pipes that should deliver it to their homes have dried up.

In a country which has plentiful natural water resources and on African terms is relatively well off, a large part of the population still doesn't have access to clean water and some of the poorest Ghanaians pay a quarter of their income on purchasing it from private sellers.

Fetching water

People are angry and frustrated over the lack of water. And many blame privatisation three years ago for their problems.

As Ghanaian's prepare for a closely contested presidential election on 7 December, the issue has become a hot topic among voters.

In one of Accra's poorest townships, Maamobi, 23-year-old Abiba and her sister, Wasila, who is only six, walk three miles every morning to fetch a gallon and a half of water.

It's not enough to meet the family's needs, but they don't have time or money to go more often.

"We usually go to the pipe at 6am. Because of the distance we only go once a day," says Aibiba. She pays the private seller ten US cents to fill up her container.

Yet mains water should be available in the courtyard of her house.

"It's very difficult here. There is a pipe but the water isn't flowing," she says.

'Water crisis'

Ten years ago, when the idea of privatising Ghana's water system was first proposed by the World Bank, local activists were alarmed

Fearing a profit-seeking company would raise the cost of water for ordinary Ghanaians, they formed the Campaign Against Water Privatisation.

For five years a fierce public debate raged. Then the World Bank and Ghana's government adopted a compromise.

A private company, Aqua Vitens Rand Limited (AVRL), was given a contract to manage the existing system, while the responsibility for improving and expanding the infrastructure remained with the government.

Still, Alhassan Adam, from the Campaign Against Water Privatisation, says since then the situation has only got worse.

"If you talk to any water consumer they will tell you the water crisis is getting worse and worse, especially in the big cities where Aqua Vitens Rand are managing the water system," he says.

"We are seeing the water system collapsing at a faster rate than when it was under public management."

Pragmatic solution

At the local medical clinic in Maamobi, midwife Dorothy agrees.

She's seen outbreaks of water related diseases like typhoid and cholera, which she blames on the lack of clean water in the community.

And if the taps run dry at the clinic, women in labour are expected to provide for themselves.

"At times we are short of water," she says. "So we normally ask them to bring water with them in a jerry can. If they don't have it, they can't bathe after the birth."

The privatisation of water utilities has proved hugely controversial elsewhere in the developing world, notably in Tanzania and South America.

But the World Bank says it is underinvestment - not privatisation - that is to blame for Ghana's poor water supply.

The World Bank's Country Director for Ghana, Ishac Diwan, says partial privatisation is a strategy for overcoming corruption and inefficiency in the state system.

"Its not about ideology. Its pragmatic," says Mr Diwan. "What we're trying here now is a middle-ground solution."

Illegal connections

The operating company which manages Ghana's water industry is a consortium of two state-owned companies, Vitens from the Netherlands and South Africa's Rand Water.

Its job is to reduce costs, maintain the existing pipe network and chase up the many thousands of illegal connections to the water supply.

That inevitably causes resentment.

AVRL's chief executive, Andrew Barber, feels his firm is unfairly blamed for the wider problems caused by a lack of investment.

Mr Barber says the actual operating remit of the company is quite narrow.

"What we're trying to do as the operator is just manage the day-to-day running of the water supply," he says.

"For us, it's really important we get out into these areas which haven't had water for many years and fix burst water mains and meters and keep the water flowing in pipes."

Aging system

The population of Ghana's cities is growing rapidly as people move from rural to urban areas in search of a living.

The World Bank estimates half a billion dollars would be needed to resolve water supply problems in Accra alone, with another half a billion at least for the rest of the country.

In Nima district, another of Accra's poorest townships, AVRL points to the recent reconnection of water supplies after several dry years.

Residents of the low-rise concrete houses and narrow alleys of Nima celebrated when they could leave their jerry cans and buckets at home.

But as if to illustrate the scale of the task ahead, within a few days the water was off again.

The increased pressure in the pipes had caused the aging mains system to disintegrate. Men are now busy digging up the roads to repair them.

And the jerry cans are in service once again.

General News of Wednesday, 3 December 2008

Source: BBC World Service