GhanaWeb Feature by Mawuli Ahorlumegah

Africa stands at the threshold of a defining energy transformation, and Ghana is poised to play a critical role in this agenda. Amid rising energy demand and climate imperatives, the nation must navigate a complex path by leveraging oil while accelerating renewable energy and nuclear power, supported by strengthened climate-change institutions.

Ghana’s energy mix – vital numbers and challenges

Ghana’s electricity access stands with more than 88% of households connected to the grid, but reliability remains uneven.

The power supply depends heavily on hydropower and thermal plants, which together contribute over 70% of generation. Oil and gas reserves, primarily from the Jubilee, TEN, and Sankofa fields, remain critical to both revenue and energy security.

Yet, Ghana’s reliance on fossil fuels poses vulnerabilities due to rising fuel import costs, growing greenhouse gas emissions, and exposure to global price shocks. Meanwhile, renewables account for only about 1% of installed capacity, far below the government’s target of 10% by 2030.

LEAF Project assesses renewable energy hotspots in Ghana

Renewables: Vast untapped potential

Ghana is endowed with abundant solar resources, averaging 5.5 kWh/m²/day in solar irradiation. Wind corridors along the coast and in the Volta Region also hold some promise. For instance, projects like the 50 MW Bui Solar Plant demonstrate progress, but scale remains limited.

Challenges include high upfront costs, limited grid integration, and regulatory bottlenecks. To accelerate deployment, Ghana must provide incentives for private investors, streamline permitting processes, and expand public-private collaboration.

Nuclear Energy: On the horizon

Ghana is preparing for its first nuclear power plant in the 2030s through the Ghana Nuclear Power Programme, in partnership with the International Atomic Energy Agency, which is an intergovernmental organisation that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy.

Nuclear energy offers a low-carbon, large-scale baseload option that could significantly reduce Ghana’s dependence on oil and gas. However, it requires strong regulatory oversight, investment in human capacity, and long-term solutions for waste management.

Climate minister proposes use of carbon credits to ease climate financing

New climate institutions and leadership

Under President John Dramani Mahama’s current term (since January 2025), Ghana has taken bold steps in climate and energy governance:

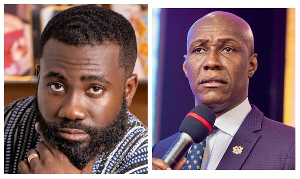

The government established the Ministry of Energy and Green Transition, tasked with steering Ghana’s shift towards cleaner energy sources while ensuring energy security. The ministry, headed by John Abdulai Jinapor, serves as a central coordinating hub for climate and energy initiatives across government, effectively “realigning government machinery” for stronger climate action.

President Mahama also created the Office of the Minister of State for Climate Change and Sustainability at the Presidency to work hand in hand with the new ministry in overseeing climate policy and cross-sectoral coordination.

Issifu Seidu was appointed as the inaugural Minister of State for Climate Change and Sustainability, signalling Ghana’s intent to institutionalise climate leadership at the highest level.

The administration is also developing a Climate Hub, which will serve as a one-stop innovation and technical support centre in collaboration with the University of Ghana, to drive research-based solutions to climate challenges.

In June 2025, President Mahama joined the Board of the Global Center on Adaptation (GCA), raising Ghana’s profile in Africa’s climate adaptation financing and policy space.

These institutional reforms represent a major shift in Ghana’s climate architecture, blending energy transition policies with global engagement and local innovation.

President John Dramani Mahama hosts Green Climate Fund leadership

Actionable solutions for Ghana

• Diversify the Energy Mix – Scale up renewables to meet the 10% target by 2030 while using oil and gas revenues to fund clean infrastructure.

• Leverage the Climate Office and Hub – Provide adequate funding and ensure cross-ministry collaboration for effective policy implementation.

• Mobilise Climate Finance – Use Ghana’s new institutional framework to attract international green funds, concessional lending, and carbon market opportunities.

• Build Human and Regulatory Capacity – Train personnel in renewables and nuclear technologies while strengthening oversight bodies.

• Boost Energy Efficiency and Decentralisation – Encourage rooftop solar adoption, set stricter appliance standards, and reduce grid losses.

• Expand Regional Integration – Maximise opportunities in the West African Power Pool through cross-border hydropower and hybrid projects.

Conclusion

At the moment, Ghana stands at a pivotal crossroads. With oil revenues still crucial, renewables underdeveloped yet promising, and nuclear power on the horizon, the establishment of new climate institutions offers a pathway toward a balanced, sustainable future.

By harnessing leadership, unlocking green finance, and driving innovation, Ghana can power Africa’s energy transition and secure a resilient, inclusive, low-carbon future.

Ghana pushes for stronger collaboration on climate action

Business News of Thursday, 21 August 2025

Source: www.ghanaweb.com