- Home - News

- TWI News | TV

- Polls

- Year In Review

- News Archive

- Crime & Punishment

- Politics

- Regional

- Editorial

- Health

- Ghanaians Abroad

- Tabloid

- Africa

- Religion

- Election 2020

- Coronavirus

- News Videos | TV

- Photo Archives

- News Headlines

- Press Release

General News of Thursday, 30 May 2002

Source: BBC

Ghanaian films grow despite tensions

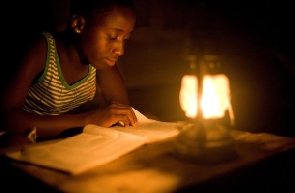

Whilst the majority of African filmgoers continue to enjoy Indian and American films, low budget, local films are becoming a growing art form in West Africa. In 2001 over 500 films were produced in Nigeria and around 100 were produced in Ghana.

As Franklin Kennedy, a researcher into the Ghanaian film industry, told the BBC World Service, their popular appeal owes much to the audience's need to identify with the characters.

"They are popular with young people as they can identify more with these movies. They see themselves reflected in these movies."

Talk

Locally produced films can attract tens of thousands of people to watch them in one of Accra's many cinemas.

Afterwards, discussion groups often gather to reflect on the film's significance.

"There are video shops, retail shops and video cafes where people come together and watch some of these tapes.

People just come and discuss these videos in groups," Mr Kennedy explained.

"It goes to show how popular and how important this sphere of popular culture is today."

Battle

Many of the films thrive on the conflict between "powers of light" and "powers of darkness".

Placed in the framework of the Christian dualism of God and the Devil, it is always the Christian God who wins, whilst the village witches are normally vanquished.

Religion plays an explicit part in these locally-made films explained the Reverend Dr Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu.

"These films affirm the traditional African world view of the existence of power encounters between the God of creation and the evil powers that Africans believe in.

"As Africans and Ghanaians we all know that these things happen."

Tension

According to Ghanaian film maker William Akuffo, this battle of good and evil comes as a direct response to "what the audiences demand."

But with many films apparently relishing the dramatisation of the occult, censorship of locally produced films is tightening.

"In one of my films you can actually see witches flying, but the censorship people came down to us and were like, 'no this is your last witch film'," Mr Akuffo explained.

But, he went on to insist, not all imported films go through the same stringent checks.

"If now we see a lot of Nigerian films coming into our market and they have very explicit scenes in them, I don't understand what the censorship people are trying to tell us as film producers. You can't do it, but others can and bring it into our market."

Dr Brian Larkin, of Columbia University, told the Omnibus programme, the confusion of what should be left in the film and what should be excluded, also extends across the border to Nigeria.

"There is a tension in Nigerian between northern, Hausa based produced films, and Lagos based videos.

"For many northern Nigerians, Muslims, who live in a society which is fairly strictly Islamic, what goes on in Lagos videos is often seen as culturally too avant-garde and too licentious."