- Home - News

- TWI News | TV

- Polls

- Year In Review

- News Archive

- Crime & Punishment

- Politics

- Regional

- Editorial

- Health

- Ghanaians Abroad

- Tabloid

- Africa

- Religion

- Election 2020

- Coronavirus

- News Videos | TV

- Photo Archives

- News Headlines

- Press Release

Opinions of Friday, 8 July 2016

Columnist: Badu, K

Gender equality: Why does class struggle matter for women's liberation

In our anfractuous society, most women are believed to be discriminated against in all walks of life, including jobs, pay, education and welfare.

Ironically, however, it used to be said that women must do twice as well as men-to be seen half as good. Yet young women are often encouraged to see marriage and the family as their only viable means in life, and are therefore routinely dissuaded from learning most skills or studying the same subjects as boys.

Apparently, in career options, women are mostly pointed in the direction of jobs such as selling petty goods, dressmaking, and hair dressing to pass off time till they get married and have babies. Then they get married with high hopes of a perfect family life—but it doesn't often work out like the ideal family of the millionaire’s dreams, especially when money is insufficient and a partner’s job somehow insecure.

It is also an acceptable fact that a sizeable number of women are financially dependent on a man, and without meaningful help, they Often cumbrously look after children and care for the sick and the aged.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, the feminists groups hold an arguable view that society's opinion formers’-- ranging from judges to journalists, politicians to technocrats, view women as second class citizens who often fail to utilise their perceptual powers of the mind to good effect.

It is also true that society gives oxygen to the damning assertion of women natural role to look after home and children and men role as bread winners.

Inevitably, in order to keep up with these domestic duties, women are often expected to give up everything else; education, work (or at least decent, well-paid work), and outside interests of all kinds, including political activity.

Paradoxically, however, a typical woman is expected to devote herself virtually to the care of a man, her children and parents in their old age.

In practice, the vast majority of women do what is expected of them and devote a great deal of love and care to their families, often in very difficult circumstances, thus, society somehow assumes that women are narrow-minded, or at least simple-minded,unable to comprehend what goes on outside the home.

It is also a common belief that most women are economically dependent on men because they cannot carry the burden of household tasks and hold on to a decently paid full-time job as well, and that makes society to assume that women are dependent on men because they are invariably feeble and helpless without them.

Even when women are engaging in other gainful activities alongside their domestic duties, society still cynically sees them as domestic servants. For however hard they try, the odds remain stacked against them in spite of their relentless strides to keep up with men.

There is also a school of thought that frets if women ‘swamp’ the labour force rather than look after their children, this will boost GDP but create negative social externalities such as a lower birth rate. Yet developed countries where more women work such as Sweden and America, their birth rates are higher than Japan and Italy, where women stay at home (the economist print edition, April 2006).

Some sceptics however fear that the influx of women in the paid labour force can come at the expense of children. Yet the evidence for this is diverged. For what is evidential is that in countries such as Japan, Germany and Italy, which are all harshly faced by the demographics of shrinking populations, far fewer women work than in America, let alone Sweden (Economist 2006).

In hindsight, if female labour-force participation in these countries rise to American levels, it would give a helpful boost to these countries' growth rates.

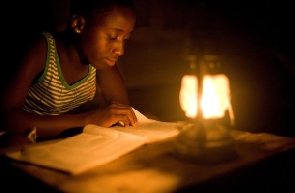

On the other hand, in developing countries where girls are less likely to go to school than boys, investing prudently in education would deliver huge economic and social returns. For not only will educated women be more productive, but they will also bring up better educated and healthier children.

The general believe is that more women in government could also boost economic growth, for studies show that women are more likely to spend money on improving health, education, and infrastructure and poverty and less likely to waste it on tanks and bombs (Economist 2006).

Nevertheless, most women are mostly held up in the family circles. For however much they love their husbands’ and children, they know they have little choice about it. For it is harder for a woman than for a man to get out of a marriage that has gone wrong, and most women whose marriages break down are often left to bring up children on their own with little or no support.

More worryingly, many women are ‘stuck’ in their homes by violence or the threat of it. For some men end up harming the woman they live with because they are ground down at work or don't have enough money to meet their family's needs-they make women escape goats for what isn't their fault, and most women have no way of fighting back and nowhere to turn to when this happens.

What kind of society is it that puts women in this position? It is only a society that insists that the family is 'private', and that women somehow belong to the men they marry as if they were pieces of personal property.

“In rape, women are exposed to a kind of violence which men don't face, perhaps the most humiliating of all. Women are encouraged to look sexy and attractive to men, and to feel as free as men to enjoy themselves-a freedom long overdue after centuries of a double standard for men and women-but when an attractive woman is raped most men think she must have been 'asking for it”. How can women feel free when this unfairness is going on under their noses?

For in our society, it appears that women don't have equality, they don't have freedom, and they don't even have respect and dignity in any meaningful sense. What can be done about it?

Well, women have to remain resolute and be prepared to fight back, for themselves and for the future of all women. This doesn't mean an out-and-out conflict with all men all of the time. For separatism-the view that women can battle for liberation only on their own and against men-is an admission of despair and a way of keeping apart women and men still further.

All the same, women have a right to organise with men to fight against the society that keeps women down, to make men see that the world has to be changed. This, however, doesn't mean that women can't organise their own meetings, demonstrations, pickets or whatever, when necessary-we have that right too—but we should be trying to reunite women and men in the struggle for peace and equality.

Apparently, the discrimination against women is a quagmire which requires the attention of the wider society. The big question though is: Why does class struggle matter for women's liberation?

K. BADU, UK.