Statistical data relating to election disputes instituted after Election 2008 indicates that 70 per cent of the cases were commenced by writ of summons instead of petitions and were accordingly struck out.

“In one region alone as high as 17 writs of summons were filed instead of a petition and were dismissed for wrong procedure as the situation which most often creates the erroneous impression that the Courts were out to frustrate electoral adjudication.

“It is incumbent on Lawyers and people seeking for redress to enter through the right procedure as wrong process would lead to the case being thrown out and potentially increasing tension,” Mr Justice John Bosco Nabarese, First Deputy Secretary of the Judicial Service, said at the weekend.

He said out of the remaining 30 per cent, only a negligible number are still pending at the Courts, stressing that in spite of the challenges the Judiciary is ready to deal with Election 2012 disputes swiftly.

Justice Nabarese said this at a workshop organized by the Legal Resources Centre (LRC), an NGO on Human Rights, which is aimed at strengthening the Judiciary to deal with human rights abuses during Election 2012 and also map-up strategies to build public consensus on electoral disputes.

The LRC also seeks to use the engagement to empower stakeholders to effectively resolve electoral disputes amicable.

Justice Nabarese said the Judiciary is currently in the process of reviewing an elections manual which would list the protocol for bringing a challenge against any election in Ghana.

He explained that the 1992 Constitution provides that the declaration of the Presidential Election might be challenged by a petition to the Supreme Court saying “based on the mandate given by the Constitution, the Rules of Court Committee has made rules of procedure as to what constitutes a petition so far as challenges to the Presidential elections by a petition are concerned.

“Pursuant to Article 64 (1 & 3) any citizen of Ghana who is registered as a voter may present a petition challenging the election of the president to the Supreme Court within 21 days of the declaration of the Presidential results”.

Justice Nabarese said in order to commence a challenge to a parliamentary election, a petitioner must satisfy the High Court that he or she has the necessary capacity to initiate the petition.

“If the Court is satisfied that the petitioner is clothed with the capacity to institute the petition, the court can hear its substance, but if not, the petition should be dismissed for lack of capacity on the part of the petitioner.

“To this end, section 17 of the Representation of the People law, 1992 (PNDCL 284) as amended, provides that an Election Petition may be presented within 21 days from the publication of the results in the Gazette,” he said.

Ms Daphne Lariba Nabila, LRC Acting Executive Director, said in view of legal challenges associated with election disputes, the Centre has embarked on advocating for a specialized legal mechanism to deal with election disputes with the objective of improving the process and eliminating the violence that surrounds potential election disputes.

“To this end we have developed a manual for the benefit of citizens and law enforcement bodies. The right of Ghanaians to peacefully challenge election results and elections offences through the court is a right that is rooted in the Ghanaian Constitution,” Ms Nabila stated.

The manual: “Summarized Manual and Statutes on Elections Adjudication in Ghana,” contains a wealth of information on the legislation and legal mechanisms for dealing with election disputes as they arise.

The manual discusses which courts are empowered to hear which kinds of disputes and which cases may be appealed, who is allowed to bring legal challenges of election results and how they must do so, and contains a summary of particular offences which might occur during an election and may be resolved through the Ghanaian legal system. The project is being sponsored by STAR-Ghana, a multi- donor pooled funding mechanism (Funded by DFID, DANIDA, EU and USAID) to increase the influence of civil society and Parliament in the governance of public goods and service delivery, with the ultimate goal of improving the accountability and responsiveness of government, traditional authorities and the private sector.

General News of Monday, 9 July 2012

Source: GNA

Election 2008 disputes wrongly filed

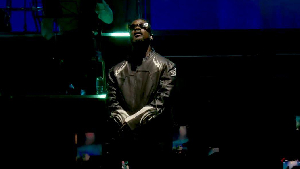

Entertainment