I can hear Bawku weeping, not only in silence but in loud, aching cries.

And I do not understand why a nation blessed with enlightened leaders, men and women equipped with wisdom and analytical skill, continues to allow this land to bleed.

Why has Ghana denied peace a chance in Bawku, one of its most underserved communities? Why has Bawku, a town where children no longer dream and mothers no longer sleep in peace, not been given the needed attention?

Bawku is a land forgotten by peace and forsaken by the very nation that once vowed to protect her.

Once, Bawku was a proud town, famous for its rich culture, vibrant trade, and the dignified resilience of its people.

Its markets thrived with the colours of cross-border commerce, attracting goods and buyers from Burkina Faso, Togo, and across northern Ghana.

Kusasis and Mamprusis shared space, not without differences, but with tolerance.

They intermarried, celebrated festivals, and built communities side by side.

But today, all that remains is ruin. People now whisper instead of speaking.

They run instead of walk. And they mourn more often than they smile.

What happened to this town? How did a place once filled with promise become a battlefield of pain?

How did Ghana’s own children come to fear their homeland more than they fear the unknown?

The guns did not begin yesterday. The roots of this violence stretch back nearly a century, when colonial administrators imposed foreign structures of authority on indigenous communities.

They divided what was once whole, deciding arbitrarily who should rule and who should obey. But instead of healing, the postcolonial state picked a side, and the wound deepened.

In 1958, the CPP government passed legislation naming the Kusasi chief as the rightful occupant of the Bawku skin, reversing years of colonial favouritism toward the Mamprusis.

That decision, though legally grounded, ignited a cycle of contestation and grief that has erupted violently time and again, in 1983, 2001, 2007, 2013 and now again, relentlessly, since 2021.

The result? Blood in the streets. Fear in the homes. Silence in the statehouse.

Between late 2021 and 2023 alone, dozens have died, some shot in broad daylight, others caught in the crossfire of reprisal attacks.

Innocent civilians, including women and children, have been hunted not by enemies from outside, but by neighbours and histories left unresolved.

The military has been deployed, but peace has not followed.

Instead, questions multiply.

Accusations of bias, indiscipline, and even brutality haunt the security forces, further eroding public trust.

Today, curfews confine people to their homes like prisoners.

Motorbikes, once vital for trade and transport, are banned.

Schools are closed. Hospitals stand overwhelmed or abandoned.

In 2023, even final-year junior high school students had to be relocated under armed escort just to sit their exams.

This is not peace, it is a slow death.

And through it all, Bawku weeps in silence, because no one is listening.

How many more children must grow up counting corpses instead of candles on a birthday cake? How many more women must bury their sons and husbands before Ghana finally calls this what it is, a war?

How many times must the people of Bawku cry, “We are Ghanaians too,” before someone truly hears?

Where is Parliament?

Where are the ministers, the regional councils, the peace architects this nation claims to honour?

Where is the President’s bold initiative, the legal clarity, the fair but firm enforcement of peace?

Ghana cannot claim to be a beacon of African democracy while its own children are dying unnamed in the north.

It cannot raise flags at peace summits abroad while allowing entire communities like Bawku to disintegrate at home.

The people of Bawku are not asking for favours.

They are demanding justice, safety, dignity, and peace.

They want the chieftaincy dispute settled—finally, transparently, and permanently.

They want security forces that protect, not provoke. They want their schools reopened, their markets restored, their nights quiet.

They want to sleep without fear. They want their children to dream again.

And we must ask ourselves: How did we allow our own citizens to be silenced by the sound of gunfire?

Is peace in Ghana only reserved for the south? If Bawku were part of Accra or Kumasi, would the response have been this slow?

Because silence is killing Bawku—silence from government, silence from the south, silence from those who still see this as a distant, ethnic matter, not a national crisis.

But Bawku is not just a northern town. Bawku is Ghana.

Its people are Ghanaians. And every bullet fired in Bawku is a crack in the foundation of our peace. Every child buried is a blow to the future we all claim to build.

Bawku is weeping.

The question is: Will Ghana finally hear her cry?

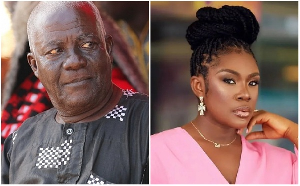

Joseph Odoom

A student at the Legon Centre for International Affairs and Diplomacy (LECIAD), University of Ghana.

Opinions of Monday, 11 August 2025

Columnist: Odoom Joseph