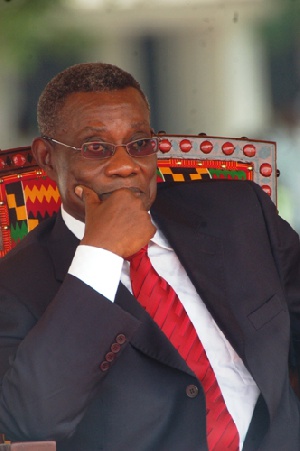

Ahead of elections, President Mills has promised stability, growth and jobs in his 2012 budget, but ending a bizarre cycle of fiscal maladministration as the poll approaches could be his biggest test yet.

Presenting next year’s budget to Parliament on Wednesday, Finance Minister Dr. Kwabena Duffuor projected strong growth of 9.4 percent, average annual inflation of 8.7 percent and said the gains of stabilisation will be preserved.

“Notwithstanding the fact that 2012 is an election year, the NDC government will maintain the fiscal consolidation achieved so far,” he assured.

Vice president, John Mahama, has also said the government will tighten its grip on the public purse during the election season to avoid a repeat of past mistakes. But despite the assurances, there is still concern -- both within and outside Ghana -- about whether the government can avoid a fiscal slippage in the upcoming election year.

History suggests this concern is well-founded. In the past (particularly 2000 and 2008), governments, including the previous NDC administration, have let the economy slip their grasp as they came under pressure to spend to placate voters.

And before the damage was done, there had been plenty assurances. Here’s what Kwame Peprah, finance minister under ex-president Rawlings, said in 2000 in his budget speech: “This is an election year, but the charge from the president is that we should not allow the elections to distract us from the work which lies ahead during the year.

Indeed, we must resist the temptation to play political football with the economy in this election year. Populist demands, populist rhetoric, blackmail threats (and) wildcat strikes all combined to wreak havoc on the progress of our economic forward march during the two previous elections in 1992 and 1996.

Let us all take note, however, that when the economy goes off course in an election year, it takes years of belt-tightening and further harsh fiscal measures to bring it back on course. We must all undertake to put Ghana first even though it is an election year.

Let us all accept that whatever damage may be done in this election year, the party that wins will find it difficult to repair it. Since each of our parties believes that it will win the elections, we owe it a collective responsibility to the people of Ghana to exercise discipline in our discussion and in our handling of the economy.”

In the end, however, his worst fears came to pass, and the economy wound up in grim circumstances: inflation run at 40.5 percent, the government was borrowing short-term at 38 percent and banks were lending at 47.5 percent.

To be fair, all of it was not the government’s doing. By some accident, the global economy had not been in favourable shape in each of the 2000 and 2008 election years, and had been partly responsible for the problems at home.

In 2000, a fall in cocoa prices, a key foreign-exchange earner, to a thirty-year low of US$506 per tonne hurt export earnings and taxes. Meanwhile, oil prices surged from an average of US$18 per barrel in 1999 to US$31 in 2000, raising the oil-import bill by 56%.

The combined effect of these external shocks, amid an underlying debt overhang, triggered runaway inflation and brought down the currency.

Similarly, in 2008, no one had expected the price of a barrel of crude to touch US$147 by July; in fact, the authorities had forecast an average price of US$80 before the year began. And by the time the oil price peaked, import tariffs had had to be slashed to mitigate the impact of a surge in global food prices.

In the absence of the necessary fiscal restraint, the year ended with a budget hole that cost 8.5% of GDP (using recently revised output figures) and a current account deficit at 10.8% of GDP.

Each of these episodes threw up serious macroeconomic difficulties for the new government that was elected -- and the real sector suffered, too. Businesses borrowed expensively, and the belt-tightening caused pain to many households.

In February 2001, two months after the former administration, the New Patriotic Party (NPP), had been sworn into office, Ghana declared itself a heavily-indebted poor country (HIPC) and signed on to a debt-forgiveness programme with external creditors.

The public debt was a whopping 124% of GDP. Everywhere in government circles could be heard righteous rhetoric about the ills of fiscal imprudence -- and the importance of macroeconomic stability for sound economic growth.

When the NPP left its own legacy of large domestic and external deficits in January 2009, President Mills and his new administration sought succour in the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, which provided loans to sustain poverty-reduction programmes, and foreign exchange to build up the Central Bank’s depleted reserves.

In both 2000 and 2008, the magnanimity of Western creditors helped to ease the pain and restore confidence in the economy. That is one reason why there is anxiety among officials of the World Bank, the IMF and other Western donors over how macro-economic policy will be conducted when voters gain the initiative during next year’s elections.

At a recent meeting between government officials and representatives of Western donors, the latter cautioned thus: “There are high risks of fiscal slippages in the period ahead... relating to the upcoming elections which will increase the political pressures for spending.

“[Our] call on the government is to avoid the easy temptations of deficit-led growth in the coming period -- the costs of stabilisation that the country had to bear in the past three years attest to the destructive nature of these short-term and myopic temptations.”

So, will Mills break the jinx? That is uncertain, according to analysts. What is clear is that he must prepare for the worst -- both at home and abroad.

Given the ambush of the global economy by the Arab Spring and persisting debt problems in rich countries, every prognosis on the world economy is given to uncertainty; and it is hard to imagine trade unions, whose total wage entitlements under the new pay policy have only been partially paid, not taking to the streets in an election year. Mills’ “Better Ghana” agenda may just be up for its biggest test yet.

General News of Friday, 18 November 2011

Source: BFT