Opinions of Friday, 6 July 2007

Columnist: Asare, Kwaku S.

Can Judicial Inefficiency lead to Mob Justice, Vigilantism and Spiritual Justice?

Disputes are inevitable in any social entity and the mode by which societies resolves these disputes is an important determinant of their rate of growth and development. Who owns a piece of property? Who is the rightful occupant of a particular stool? Under what circumstances can the Republic detain a suspect? Does a candidate hail from or reside in a particular constituency? These are examples of common and recurring disputes in a society. Unless a society designs a timely, reliable and a fair mechanism for addressing these disputes, the disputants are likely to fashion their own private solutions, which often take the form of mob justice, vigilantism, and spiritual justice. Whatever the initial form of these private solutions, they ultimately lead to chaos and anarchy, sapping society of the peace needed to engage in progressive activities.

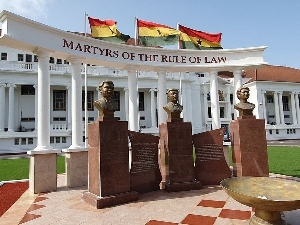

Realizing this potential for anarchy, the framers of the 1992 Constitution created a Judiciary and invested in it the sole and exclusive powers of resolving many of these disputes using rules announced in advance and known or presumed to be known by potential disputants. To be a relevant dispute resolving mechanism, the Judiciary should be independent of the disputants, must make decisions that are justifiable in light of the laws governing the disputants, and must make timely decisions that preserve the value of the disputants’ claims. The latter criterion, which is the subject of this article, is a measure of judicial efficiency.

I define judicial efficiency in terms of the speed with which judicial decisions are made. The operational measure of judicial efficiency is the number of days between the filing of a case and its ultimate disposition by the court system. The importance of efficiency in the delivery of justice is captured by the maxim “justice delayed is justice denied.” Needless to say, delays are inevitable in any system of justice that values and must follow due process. The maxim “justice rushed is justice crushed” underscores the importance of adhering to a speed limit on the highway of justice. Thus, the efficiency question is not about whether there are delays but whether the delays are excessive and unreasonable.

There are many reasons why efficiency is important. First, many, if not all, claims have time dependent values. Consider a farmer who contracts on January 1, 2009 to export yams to an overseas importer on December 31st 2010. In anticipation of that contract, the farmer acquires land on the contract signing date. However, on February 1, 2009, a builder commences construction on the farmer’s land, which compels the farmer to initiate litigation in the high court on that same day. The farmer is here not merely asking the court to declare the true owner of the land but to do so timeously for him to fulfill his overseas contract. Declaring him the true landowner on December 31st 2015 is entirely useless to him, especially if the recalcitrant builder is not made to bear the damages arising out of the farmer’s likely breach of the overseas contract.

Second, judicial inefficiency emboldens potential law breakers. The recalcitrant builder’s conviction that the judiciary would not timely resolve any ensuing dispute and his hope that the resulting unreasonable delay would overwhelm the aging farmer’s patience may have played an important part in his decision to trespass. Third, judicial inefficiency leads to forced investments and choices. For instance, in anticipation of the land encroachment, the farmer will erect a structure whose sole purpose is to keep the encroacher at bay. Of course, there is little guarantee that such a structure will fulfill its sentinel role.

Fourth, unreasonable and excessive delays reduce the probability that the courts will get to a correct resolution, which undermines the integrity of the process. Cases that are delayed are associated with loss of witnesses, judges, and other parties (either through death or other reasons) and the fading of memories of available witnesses.

Fifth, in criminal cases, such delays undermine article 19(1) of the constitution, which is in the form of “[A] person charged with a criminal offence shall be given a fair hearing within a reasonable time by a court.” Sixth, delays increase the direct and indirect cost of litigation to the parties. Direct cost includes additional, probably unnecessary, payments to lawyers. Indirect costs include opportunity costs of being involved in an endless litigation.

Finally, judicial inefficiency leads to a black market for justice. Litigants, who lose confidence in the judiciary, simply veer off the “go-slow” justice highway and enter the black market of justice where they can have more efficient, even if unorthodox, adjudication.

Are the delays by the Judiciary excessive and unreasonable or necessary to safeguard the procedural rights of the litigants? Four illustrative cases affirm tell the story.

The first case involved the resolution of an electoral dispute. The importance of a timely resolution of such disputes is without doubt as winners have a limited tenure of four years. Further, because election outcome affects the distribution of power in society, needless delays in resolving them can easily escalate into larger conflicts as has happened in various parts of the world. Rebecca Addotey was improperly declared the winner of the Ayawaso West constituency in the elections of 1996. Although the trial court declared George Amoo the true winner, Addotey used the interlocutory appeals system to frustrate Amoo until the case was mooted in 2000. Similar delays were encountered in 2000 when it took over 28 months to resolve the electoral dispute in Wulensi. Currently various electoral disputes are still being litigated even though the elections were held in 2004 and new elections are slated for November 2008.

The second case involves the resolution of a dispute over the true owner of a property located in Kumasi. The litigants are Okyere Buor and National investment Bank. According to the Daily Graphic (3/17/2006), the case was filed when the plaintiff was 63. In 2006, an 80 year old Okyere Buor made a passionate appeal to the presiding judge to resolve the case before his death. As far as I know the case is still making its way on the judicial highway.

More recently the appellate case of Abodakpi v. Republic, addressing the simple but important question of whether Abodakpi can remain on bail pending the hearing of his substantive appeal, has been caught in the traffic jam on the justice highway. As is known, a resolution of this appeal also affects the right of the Keta people to be represented.

The final, perhaps the most poignant, example of judicial inefficiency is the ongoing case of Republic v. Tsikata. The case itself is a very mundane one. Tsikata is charged with three counts of willfully causing financial loss of about 2.3 billion cedis (about $5M based on the exchange rate at the time of the transaction) to the State through a loan he guaranteed for Valley Farms, a private concern, on behalf of the GNPC. The accused is also charged with misapplying public property. In effect, the State’s burden is to prove beyond reasonable doubt that a willful act by Tsatsu caused a financial loss to the State. This very simple case was initiated in 2002 and has been tried under the direction of 4 Attorney Generals (Nana Akuffo Addo, Paapa Owusu Ankomah, Ayikoi Otoo, and Joe Ghartey) and reviewed at the Supreme Court under the leadership of 4 Chief Justices (Abban, Wiredu, Acquah, and Woode). Over the life of the case, the trial court heard from a mere 12 witnesses. Even though closing arguments have been made and the trial court promised a verdict in October 2006 (postponed to December 2006, then to February, May, June 2007).

What can or should be done going forward? There is an immediate need for the Judiciary to emplace and announce an intelligent case management system that is sensitive to the life-expectancy of a disputed claim. Top on the agenda must be timely settlement of election disputes because of their potential for degenerating into uncontrollable conflicts. Mere exhortations by the new Chief Justice will not do! Rather, it is time to establish a firm publicized deadline, whose violation will exact stiff penalties. A comprehensive timeline for resolving election disputes must have a deadline for the courts to settle all disputes, including appeals. This calendar requires that pre-voting day disputes be resolved before the elections or they become “res judicata.” Morever, post-voting day disputes should also be resolved before inauguration. While the deadlines appear tough, they are sensible and necessary. Perhaps, a dedicated cadre of judges can be named during the election season to focus exclusively on the timely resolution of the disputes. Needless to say, such deadlines will not countenance adjournments and delay tactics by the Bar. Similar case management schedules should be established for all categories of cases. Judges must take charge of their court rooms and be loathe to granting adjournments, once the trial has commenced. The courts should not grant an adjournment because a party refuses to show up or to allow the Prosecution to investigate a case, for which there is an on-going trial. Parties who fail to show up should be sanctioned, including dismissing the case when appropriate. The Tsikata trial shows that the system is ripe for a variant of the “final judgment” rule. This rule will limit, with few exceptions, aappellate issues to "final judgments." The exceptions would include questions of subject-matter jurisdiction of the trial court, or constitutional questions of the gravest importance. Any such appeals, to the extent that it is hindering the trial court from proceeding with the trial, must be resolved in less than a month. The court registrar must keep track of the age of all cases and initiate communications with any judge whose trial exceeds a statutory maximum (e.g., 6 months). This “aged trial balance” must be accessible online and available for media scrutiny. Disciplinary actions must be brought against judges who consistently delay their cases. The fear that such deadlines will rush judges to make hasty decisions can be contained if judges are required to publish their opinions online. Further, the normal appellate procedures, after the final judgment in a case, will be available and the usual sanctions for judges who are frequently overruled will be applied. The Court should abandon the practice of going on summer vacations. The justification for going on a vacation when there is a huge backlog of cases is not readily apparent. The illustrative cases used here show that the judicial system is so completely, totally, and profoundly broken down that it is doubtful if it can fulfill the role and responsibilities assigned to it by the constitution. Further, unless dramatic reforms are initiated as soon as possible, the nation should brace itself for growing mob justice and vigilantism both of which will retard growth and development. So called land guards used to secure property rights or macho men used to demolish illegal structures on property are but manifestations of this black market. In civil litigation, people are resorting to settling scores on the streets rather than turning to the inefficient judicial system. Thus, a suspected pickpocket is likely to be lynched than civilly prosecuted for battery. Even the State occasionally plays in this black market as evidenced by the razing down of an airport hotel under the NDC regime.

The water level in the judicial dam is dropping precipitously. We can take steps now to address the problem or wait to be plunged into judicial darkness and a new form of “justice load shedding!”