Diasporia News of Monday, 4 June 2007

Source: NJ

No Visa, No Kidney, No Life

Kate Ocansey shouldn't have to die because of section 214 (b) of the federal Immigration and Nationality Act.

That's the law invoked by American consular officials throughout the world to deny entry visas to foreigners who want to come here temporarily for reasons usually no more nefarious than to attend a relative's wedding or see a dying parent.

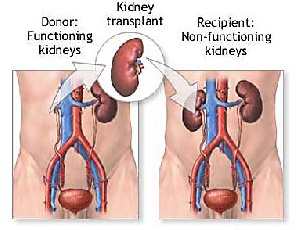

Or, in the case of Ocansey's nephew, Charles Amanfu, to save a life. Hers. By donating a kidney to her.

Asks Ocansey: "So, do I have to die just because my nephew cannot prove he won't return?"

Well, yes. Or, at least, maybe.

She says her doctors have intimated she could be dead in two years, but might live long enough -- say, five years -- to get a kidney transplant from a dead person; Ocansey is on a list for that. But, then again, she might not live that long. She is, after all, 62, suffering from what her doctors call "end-stage renal disease," and undergoing dialysis three days a week, four hours a day.

She could have one of her nephew's kidneys in a matter of weeks, if he could come here from Ghana to give it to her.

But he can't.

He can't because of section 214 (b) of the federal Immigration and Nationality Act.

It states, in part, that every foreigner who wants to come to this country temporarily "shall be presumed to be an immigrant until he establishes to the satisfaction of the consular officer, at the time of application for a visa, and the immigration officers, at the time of application admission, that he is entitled to a nonimmigrant status."

Amanfu is not eligible for immigrant status. He can't prove he is eligible for nonimmigrant status. And his aunt's life hangs in the balance.

They won't let him come because they don't believe he will return and he is not eligible to be an immigrant -- and he doesn't want to be an immigrant," says Kate, an American citizen. "So, I will die because he cannot prove that. Is that some sort of joke? If it is, it's not funny."

It also is distinctly unfunny to contemplate that someone else -- a stranger unaware of all this -- might die, too, because Charles Amanfu can't get a visa to come here to donate one of his kidneys to the woman he calls his "Auntie Kate."

It's all in the numbers. Far more people need a kidney than there are kidneys available. Or, as the National Kidney Foundation puts it:

"Many Americans who need transplants cannot get them because of these shortages. The result: some of these people die while waiting for that 'Gift of Life.'"

If Kate Ocansey could get her nephew's kidney, then there would be one more kidney available for someone else. She would be off the list. No one would have to die to get a kidney to her, and she would not get a kidney that could go to someone else.

That's what families are for.

She was born in Ghana, but came here 30 years ago. Until three years ago, when she became too sick to work, Ocansey worked as a financial analyst on Wall Street. Now she doesn't do much of anything but undergo dialysis and sit in her apartment overlooking Weequahic Park, wondering whether she will die before she can get a transplant. From her nephew or from anyone else.

"I feel very weak all the time," she says. "And I used to be very active. Now, sometimes after dialysis, I just sleep all day."

She has family here -- a daughter Michelle, who recently graduated from Temple, a brother Wilfred, and nieces and nephews. None is a match for a transplant. Among all her family members, only Charles, who has undergone tests in Ghana, is a match.

"He is a match and is willing to come here," Ocansey says. "He is willing to give one of his kidneys to his Auntie Kate."

Her brother Wilfred, who lives in Burlington, is an auditor for the New York State Department of Taxation. He has formally invited Charles here and has pledged to pay all his expenses. He says he will be financially responsible for his nephew.

Charles, 46, is married and has four children. He owns a cocoa farm in Somanya, a town some 50 miles east of Accra, the capital of Ghana.

"He is not going to leave his family and a prosperous farm to try to stay here," says Ocansey. "He doesn't want to live here, he only wants to save my life."

Her doctor, Raluca Coyle of Millburn, has written to consular officials asking for Charles Amanfu to be brought here for the transplant. So has Sadanand Palekar, the director of the renal transplant division at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center, and Jennifer Hinkis-Siegel, the renal/pancreas transplant coordinator at the same hospital. They wrote more than a year ago.

U.S. Rep. Donald Payne (D-10th Dist.) also has intervened on her behalf, but so far, Charles has been unable to obtain a visa.

Payne is not optimistic.

He says he and staff members have tried for more than a year to persuade consular officials in Ghana to change their minds, but they just won't budge.

"Maybe she'll just die and then they'll go on to the next case, as if nothing ever happened. Sounds crazy to me," says Payne.