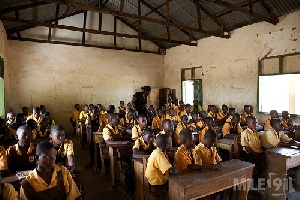

Classrooms in the over twelve thousand public basic schools (P1-P6) in Ghana re-opened the 2019/20 academic year in September without a single suitable or approved textbook in all subject areas.

The Ghana Education Service (GES) had announced a few months prior the roll-out of a new standard based curriculum for kindergarten to primary six pupils in Ghana in September 2019.

Concerned parents and the general public were left bemused and puzzled but powerless to do anything about the situation. Public school heads and teachers sounded confused but careful not to appear to “rock the boat” for fear of being victimized.

The Ministry of Education and the GES appeared strident and assured about the roll-out, countering the public criticisms from the governments political opponents whilst trying hard to allay the fears of a concerned public and parents alike.

• According to the MoE/GES, the implementation of a new curriculum (syllabus) has never coincided with the introduction of new textbooks in classroom. The latter always follows the former.

• To compensate for the anticipated lack of textbooks in the classrooms, NaCCA produced Teacher Resource Packs and had distributed over 150,000 plus copies to all basic school teachers in the country.

• The MoE/GES also intimated that the impact and importance of textbooks in the classroom was being overrated, because textbooks are only “reference” materials and not “used to teach”.

Many people have in the light of this rationalization sought to point out why these arguments form the MoE/GES are not tenable.

In the first place, it is well accepted that textbooks written for the outcome-based curriculum are fundamentally different from standard based curriculum textbooks and the expectation was that the old textbooks were not going to be used in the transitional period because they were simply unsuitable. This is more reason why every effort should have been made to synchronize the implementation with the development of the new textbooks.

So, although it was factual that the implementation of a new curriculum in the past did not take place with new textbooks, the situation we are faced with is radically different and the implementation could have been planned to make sure there were corresponding textbooks in classrooms.

There have been many questions raised about the training of the teachers for the new curriculum and the quality of the Teacher Resources Packs that were supplied to the teachers. That will require its own article and it is important that this is looked into as we examine critically the implementation challenges of the roll-out of the new curriculum.

Of greater importance though is the attempts that were made to downplay the importance of textbooks in the education delivery system at the basic level. The 2016 Global Education Monitoring Report, Policy Paper 23, makes a strong case why “Every Child Should Have a Textbook” and why the amount a country spends on learning materials is a good indicator of its commitment to providing a quality education for all. There is a growing body of evidence confirming the critical role of textbooks in improving student learning achievements.

Though there is no single “magic bullet” that will solve a countries educational problems, there is clear evidence that access to textbooks is an important part of the solution. Textbooks do matter. They play a crucial part in overcoming some of the broader structural deficits to teaching and learning. This is why the comments emanating from the GES/MoE about the importance of textbooks have been baffling.

Textbooks do matter. This is what informed the development of the comprehensive policy of the ministry of Education, The Textbook Development and Distribution Policy (TDDP) even before the country had a definitive National Book Policy.

The (TDDP) sought to “to ensure the development, selection and provision of good quality textbooks, teachers’ guides, and supplementary reading books that will promote effective teaching and learning in schools.

It provided a glimmer of hope as far as having a blueprint to regulate the textbook production process in Ghana is concerned and outlined the need for the MoE to effectively collaborate with book industry players to ensure that quality textbooks get to schools in sufficient quantities at the right time.

The initial implementation in 2004, yielded some very significant positive outcomes.

• The timely development and supply of a great variety quality textbooks by local publishers to aid the teaching and learning process

• Eradication of government’s monopoly over textbook production thereby promoting the production of quality books through competition.

• The creation of a vibrant book industry that contributes to the GDP of our economy.

Like all policies, there were some challenges, unfortunately however, the MoE never resolved to confront them to the point that the current status of this important document in the making of key decisions relating to textbook delivery and procurement is not really certain.

The current situation where the status of the TDDP is dependent or subject to importance each new leadership ascribe to it creates a great deal of confusion and may have been the main contributory factor in the lack textbooks in the classroom.

As long as the TDDP is regarded as a “mere policy”, the leadership of the MoE can choose to disregards its lofty objectives and any government may choose to either ignore its implementation or subjectively apply only certain portions.

Without an Act to back the Policy there will continue to be a lack of clarity how the education sector hopes to deliver one of its core levers in the education of especially basic schools in Ghana. In other words, the availability of a TDDP backed by law would have anticipated the major lapse we are currently grappling with and provided guidelines to avoid it.

It must be noted that through the support of the BUSAC Fund there have been series of advocacy actions on the need for the full implementation of the TDDP into law.

Though government has shown some commitment towards acceding to the demands of industry players, without codifying these positive overtures into law, any successive government could single-handedly reverse this process without any legally enforceable undertaking that the industry can take against such a move.

From a survey carried out by the Ghana Book Publishers Association in 2017, it is estimated that over $1billion has been spent on textbook procurement by government since 2004. The sheer volume of amount involved makes a strong case for legal framework to regulate textbook production and procurement in Ghana.

The book industry proposes a review and enactment of the Ghana Textbook Development and Distribution policy into an act of Parliament with clear legally enforceable under-takings for the industry to invoke in the event of a unilateral abrogation or breach.

This is the only way to ensure that quality textbooks are made available in sufficient quantities at the right time to promote effective education in Ghana.

Opinions of Tuesday, 10 December 2019

Columnist: Joseph Baffour Gyamfi