By Kofi Addo

Flags coloured with the red, black and green of Ghana's ruling party flutter feebly in the still, hot air that barely stirs above Independence Avenue as it bends down towards the sea. There it ends abruptly before the sweeping curves of grey Italian marble meant to resemble, depending on whom one asks, the stump of a tree or the buried hilt of a sword. Beneath it lies the body of Kwame Nkrumah, the country's first president and, for many millions of people, a man synonymous with Africa's liberation from colonialism.

Ghana, in 1957, was the first sub-Saharan African country to win its independence.

Yet here, at the birthplace of democracy in Africa, are portents of its fragility. On what was once the whites-only polo ground where Nkrumah declared the new state, his headless statue stands as a reminder of how a once-promising flame guttered. After declaring a one-party state and mismanaging the economy, Nkrumah was overthrown in a violent coup in 1966.

It took more than a quarter of a century before the restoration of multiparty democracy in 1992 ushered in the start of what many now call Africa's second liberation, and put an end to a cycle of military coups in Ghana interspersed only by brief periods of civilian government.

Nkrumah's heirs

More worrying than reminders of democracy's past corruption are the whiffs of its current decay. A presidential election is to be held on December 7th. But apart from a few billboards, most of them hailing the accomplishments of the incumbent, John Mahama, there are few visible signs that either the ruling National Democratic Congress (NDC) or the opposition New Patriotic Party (NPP) are campaigning vigorously for the support of voters.

The NPP's muted campaign is easily explained: it last formed a government eight years ago and its coffers are almost empty. Without a victory this year it will struggle to finance another serious bid for the presidency in four years' time.

The NDC's lackadaisical drive for votes, by contrast, reflects the insouciance of Mr Mahama. Instead of trying to win over voters through a battle of ideas, his party relies on patronage, and on spending money it does not have. Since the NDC came to power eight years ago, spending on civil servants has exploded (see chart), pushing Ghana precipitously close to a debt crisis so severe that it was forced to turn to the IMF for a bail-out last year.

Under strict supervision the government has grudgingly brought its spending under control. However, with public debt hovering at about 70% of GDP (and debt repayments accounting for a third of government revenue), its finances are precarious. Worse, it has already squandered the windfalls it expects from the development of large offshore oilfields. The roads are full of potholes, there are regular power cuts and big companies talk openly about moving across the border into Ivory Coast.

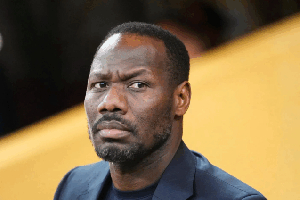

The opposition, led by Nana Akufo-Addo, a genteel lawyer and economist, would probably make a better fist of running the country with a mix of market- and investment-friendly policies. But it seems unlikely to be given the chance. "We have one party that is good at winning elections but can't run the country and another that is good in government but not at winning elections," laments one businessman.

Although the NPP's instincts are relatively liberal, it has tacked in a populist direction, with slogans such as "one district, one factory" and "one village, one dam", in a bid to broaden its appeal.

Polling data are scarce but few reckon the NPP stands much of a chance. It seems to be preparing for defeat by complaining that the election will be rigged. Charlotte Osei, the head of the electoral commission, insists that this will be the cleanest vote in Ghana's history, but she will face a tough task convincing voters of that. Many complain that the electoral roll has been stuffed with supporters of the ruling party who are ineligible to vote, because they are too young or are not citizens.

And politics in Ghana can be a grubby business at the best of times. "The 2012 election was won because of me," boasted one government minister to your correspondent. "I'm the one who did the gerrymandering." More recently a video has circulated showing Mr Mahama's motorcade driving through a market with him leaning out of the sunroof of his car handing out wads of cash.

At first his spokesman said he was handing out pamphlets, though he was at a loss to explain why they were palm-sized and tightly rolled. He later said the money was compensation for damage to some of the market stalls.

Such antics might be brushed off as theatre, but elections in Ghana are usually closely fought affairs. The winning margin will probably not be more than a few percentage points, increasing the incentive to cheat or disrupt the vote. If the result is indeed that close it will probably be contested in the courts, making it harder for Ms Osei to convince the losing side that the vote and count were fair. Many in Ghana fret that violence could break out.

Whichever party wins will have its work cut out, not only in trying to stabilise the economy, but also in tackling some of Ghana's deeper problems. Foremost among these will be to unpick a highly centralised state in which the president wields almost untrammeled power to make appointments to thousands of important posts.

These include municipal and district chief executives (the equivalent of mayors and governors) and heads of supposedly independent institutions, such as the electoral commission and the anti-corruption agency. If Ghana is to live up to its reputation as a beacon of democracy in Africa, it needs to clean itself up.

This article was amended on November 18th to note that Ghana was the first sub-Saharan African country to achieve independence.

Thanks

Kofi

Opinions of Friday, 2 December 2016

Columnist: Addo, Kofi