too slow to get there

On the global health systems landscape, the term “universal health coverage - UHC” has gained prominence in the last 3-5 years – and rightly so; in every nation, everyone (citizen or resident) should have access to health care regardless of one’s ability to pay.

The Executive Board of the WHO, reporting to the 66th World Health Assembly held recently in Geneva, noted that UHC is “…increasingly seen as being critical to delivering better health…” and proposed that member nations “…modify their health financing systems in the search for universal health coverage…”.

The need for the expansion of access to health care, particularly for the world’s poorest people, was acknowledged by all 189 UN member countries in September 2000 with the declaration of eight Millennium Development Goals to improve economic and social conditions by 2015.

In fact, three of these goals relate directly to health (maternal health; child health; HIV, TB and Malaria) and two others have components that relate to health (environmental sustainability and poverty). In a response, African leaders meeting in Abuja, Nigeria a year after the declaration of the MGDs, moved their commitments further by pledging to set aside at least 15% of their annual national budgets for the health sector.

Twelve years on, only seven African countries have been reported to have achieved the 15% target of the Abuja Declaration: Botswana, Burkina Faso, Malawi, Niger, Rwanda, South Africa and Zambia. Further, with respect to meeting the 2015 MDG targets, only eight countries are on track: Algeria, Cape Verde, Egypt, Eritrea, Madagascar, Rwanda, Seychelles, and Tunisia.

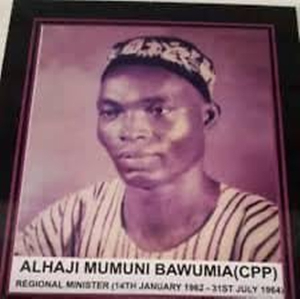

Ghana has used various mechanisms of financing health care since independence in 1957. During the period immediately post-independence, health care was financed through tax – the state providing the resources.

With time, as the burden on the state grew, user fees were introduced – where individuals and households had to finance their health care out-of-pocket. The period of the Structural Adjustment Programmes saw significant increases in user fees (commonly known as “cash and carry”) as the state’s role in social programme was reduced. The often harsh terms of the era and the attending negative impact it had on especially poor people led to the emergence of community-based health financing schemes.

These schemes evolved as communities sought to mobilize themselves to help reduce the financial risk that illness brought on people. To a large extent, it is the success of the community initiatives that laid the foundation for the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), which was introduced in 2003 through the National Health Insurance Act, 2003 (Act 650) of the Parliament of Ghana and became fully operational in 2005.

The WHO Executive Board report to the 66th World Health Assembly noted that Ghana is one of the countries that have taken important steps to move closer to attaining UHC. Indeed, having about a third of the population being active members of the NHIS stands out as a success story of the scheme.

However, there are important issues to address: studies have shown that the rich actually benefit more from the scheme than the poor - the very people the scheme was targeted to help most; there are also challenges with the claims reimbursement process (the way by which providers are paid by the NHIA for the services they render to NHIS members) - (delays and reduced amounts due to errors in processing claims – leading some providers withdrawing their services temporarily. Many experts have further questioned the long-term financial sustainability of the NHIS.

Civil Society campaigns such as MamaYe (focused on maternal and newborn health) and the Universal Access to Healthcare (focused on identifying loopholes in achieving UHC) are helping to ensure that government is efficient in its spending so as to allocate more resources for the sector.

With all the efforts being made to improve the health sector, estimates show that Ghana’s per capita health spending (spending per person) equals about US$29 and total spending on health equals about 2.6% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP – total income accruing to the nation). Health spending also accounts for about 12.6% of total government spending – falling short of the Abuja target of 15% set some twelve years ago.

The global financial crisis that hit many developed nations – our development partners – have taken a toll on how much we can expect to receive from them to support our health sector. Indeed, we need not be told that funding from these partners, however tempting the promises they continue to make to us are, will likely never reach the levels before the crisis, as they themselves need more resources to solve domestic issues.

What is the way forward for us? How can we accelerate progress towards universal coverage of essential health care services? We need to take bold steps by applying “radical” approaches like the introduction of the free maternal health care announced in 2008 by then President John Agyekum Kufuor.

We need to expand such approach to cover vulnerable groups in society – children below five years of age, people with (severe) forms of mental illnesses, irrespective of the costs. We need to take practical steps to properly identify the poor and indigent to benefit from the NHIS. Government must take advantage of the NHIS to actualize its commitments to financing health; increase tax revenue that goes to health.

At various fora, high profile government officials – including President John D. Mahama when he was Vice President - have welcomed the idea of using novel approaches (such as a percentage of revenues accruing from the oil and gas industry) to increase funding to the health sector. It is time to actualize these ideas, Mr. President.

People have recently challenged the idea of devoting 15% of budget to health and proposed that it should, instead, be 15% of actual expenses, as budget may or may not represent actual spending. However, let our government really commit at least 15% of annual budget to health – it will be a bold step! It will be important for various organs to regularly track government spending on health as a way of reminding government of its commitment; indeed, each year, it will be laudable to have our Minister of Finance report our progress toward the Abuja and other health targets.

Where is the “star” in us that sets a clear example for others to follow; that black star, rising above all else? But, it is not just the desire to be among the best nations in terms of spending on health that should motivate us; our desire to see the health of our people improve should urge us to radically raise our spending on health and ensure that the large part of the spending goes directly into provision of health services. The onus lies on our leaders and, ultimately, our President – to show leadership and commitment.

The NHIA must also ensure that the NHIS works. In fact, all stakeholders – religious, political and traditional leaders must put our hands to work. At a recent meeting in Sydney, Australia, I learned that the Aborigines of Australia usually welcome their guests with a message stick, which has several arrows pointing to one direction.

The symbol represents people working together and moving forward in one direction. We have to work together, each person bringing their ideas on board to ensure that initiatives such as the NHIS work. Together, we must do this to better the lot of our people. It is often said that “health is wealth”, but I dare say that “health is everything”.

Justice Nonvignon, PhD

MamaYe Campaign

Lecturer & Health Economist

School of Public Health

College of Health Sciences

University of Ghana- Legon

Opinions of Thursday, 18 July 2013

Columnist: Nonvignon, Justice