The recent ruling by the Court of Appeal in Kumasi, quashing a directive that required a senior lecturer at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) to apologise to two colleagues, raises uncomfortable but necessary questions about leadership and governance at one of Ghana’s most respected institutions.

KNUST has, for decades, stood as the country’s second premier university and a pillar of Ghana’s scientific, technological, and industrial advancement. Its alumni populate the nation’s engineering firms, architectural practices, laboratories, and policy corridors. With such a legacy comes a higher expectation — not only of academic excellence but also of institutional integrity and procedural fairness.

The court’s decision was clear: while the Vice-Chancellor had the authority to constitute a fact-finding committee, enforcing its recommendations in a manner that amounted to disciplinary action without adhering to due process breached the rules of natural justice.

At the centre of the dispute was a directive requiring a senior lecturer to apologise to two colleagues after a committee concluded that allegations he had made against them were untrue. The Court of Appeal held that ordering such an apology was not a trivial administrative step but one that implied wrongdoing and carried reputational consequences. As such, it required a disciplinary framework consistent with the university’s statutes and principles of fair hearing.

This is where leadership style becomes critical.

Universities are not corporations run on executive fiat. They are communities of scholars governed by statutes, collegial norms, and layered checks and balances. Leadership in such spaces must be consultative, transparent, and scrupulously compliant with established procedures. Anything less risks eroding trust — the most valuable currency in academia.

The case suggests a blurring of lines between fact-finding and discipline. While administrative efficiency is important, procedural shortcuts — even if well-intentioned — can undermine legitimacy. When a “fact-finding” process results in directives that carry disciplinary weight, it creates the perception of executive overreach.

For an institution of KNUST’s stature, perception matters almost as much as policy.

Leadership in higher education requires more than decisiveness; it requires restraint. It demands recognition that academic freedom and due process are not bureaucratic obstacles but foundational principles. When those principles are seen to be compromised, morale suffers, and internal disputes risk escalating into protracted legal battles — as this case demonstrates.

There is also a broader institutional lesson. The Court of Appeal criticised the university for failing to assist the court with full copies of its statutes. That lapse, whether administrative or strategic, points to a worrying lack of institutional preparedness in defending its own governance framework.

KNUST’s reputation as the backbone of Ghana’s industrialisation was built on rigour — rigour in science, engineering, and research. The same rigour must apply to governance.

To be fair, university leadership often operates under complex pressures: staff conflicts, student unrest, political expectations, and public scrutiny. Decisive action may sometimes seem necessary to maintain order. But the test of strong leadership is not how swiftly decisions are made, but how firmly they rest on lawful and transparent processes.

This episode should not be read as an indictment of individuals alone, but as an opportunity for institutional introspection. It is a moment for KNUST to reaffirm its commitment to procedural fairness, strengthen its internal grievance mechanisms, and clarify the boundaries between investigative and disciplinary bodies.

As Ghana’s higher education sector expands and faces increasing scrutiny, governance standards at flagship institutions must set the tone. If KNUST — with its proud history and national importance — cannot model best practices in due process, smaller institutions may feel even less compelled to do so.

Leadership at a university is ultimately about stewardship. It is about protecting the institution’s legacy while ensuring its systems are resilient, lawful, and fair. The Court of Appeal’s ruling is a reminder that even venerable institutions are not immune from scrutiny — and that credibility, once strained, must be carefully rebuilt.

For KNUST, the path forward lies not in defensiveness, but in reform and recommitment to the principles that made it great.

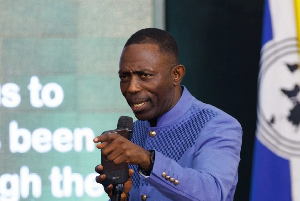

Isaac Justice Bediako, Broadcast Journalist, EIB Network – Kumasi

Opinions of Friday, 20 February 2026

Columnist: Isaac Justice Bediako