Reparations discourse within Pan-African movements has too often centered on race while marginalizing gender, thereby reproducing the very hierarchies colonialism imposed.

This omission is not merely theoretical; it has material consequences that leave African women to bear the burden of history without receiving redress. A reparations movement that fails to center African women risks becoming another project in which women’s labor is mobilized while their needs are sidelined. Justice that is not woman-centered is structurally incomplete.

As Margaret Mbira, a women’s rights advocate from Kenya, asserts: “Reparations must be structural, not symbolic. They must address both past and ongoing extractions.”

Colonialism did not invent patriarchy, but it hardened and weaponized it by restructuring African societies in ways that privileged men as intermediaries of colonial power while dispossessing women of political authority, land rights, and economic independence.

Precolonial systems that recognized women’s leadership and economic autonomy were dismantled and replaced with rigid gender hierarchies enforced through colonial law. These hierarchies persist in both contemporary governance and reparations movements.

“We need to hold our colonizers accountable. We need to be able to force on them the responsibility of what they did us all. This is where the demand for reparations come in.”

In a conversation with activist Mbira, it became clear that African women have long practiced reparative economics through mutual aid, cooperative trading, rotating savings systems, and community‑based care networks.

These systems represent living traditions of resistance and survival—rooted in collective well‑being rather than extraction. Rather than imposing external economic models, reparations should strengthen and scale these women‑led systems, recognizing them as legitimate foundations for economic sovereignty.

“In essence, women must secure land ownership and rights. There should be initiatives that put women’s need on a scale of priority.”

In her powerful reflections on ‘The Matriarchal Debt from the Capture of Female Labor,’ Margaret Mbira confronts one of the most systematically erased foundations of global wealth: the unpaid, coerced, and exploited labor of African women.

From slavery and colonialism to modern capitalist economies, African women have carried the material and social burden of production, reproduction, and community survival, while receiving little recognition, protection, or compensation.

“As part of reparations, both men and women should come together to acknowledge the efforts made buy the woman. The woman must be given all that she deserves.”

When asked about urgent steps to take regarding the demand for addressing matriarchal debt in connection with reparations, she responded:

“We must begin by recognizing the extraction of women’s labor during the Maafa. In the context of reparations, we must address not only the stolen resources, but also the forced removal of African women from the continent. African women’s labor was systemic, it was captured and exploited during slavery.”

The interview confirmed that urgent reparative steps must therefore include targeted redress that accounts for gendered violence, reproductive exploitation, and the inter generational consequences borne disproportionately by African women and their descendants.

This means investing in African and diasporic women’s economic sovereignty, health, education, land access, and political power as a corrective to centuries of enforced extraction.

It also requires honoring African women as foundational architects of survival and resistance, both during and after slavery, rather than treating them as peripheral victims.

“As women, we need to learn more about both past and present history. This will help us understand the realities of our past that still confront us today. We need to unite as a team and ensure our voices are heard—especially on issues of reparations. Our voices must be heard from the continent and beyond,” the activist emphasized, outlining key pathways necessary to win the fight for reparative justice.

Therefore, PPF and Pan-African organizations can play a vital role by organizing and mobilizing communities to deepen understanding of our history and the roots of our ongoing struggle.

“The Pan‑African Progressive Front (PPF) has intensified its engagement with the discourse on reparations and matriarchal debt,” advocate Mbira said. Central to this work is the PPF’s conviction that reparations and women’s liberation are politically and historically intertwined.

Since concluding its conference for Progressive Forces, PPF has advanced the agenda through two key departments: the Women and Youth Department and the Reparations Department. Together, these teams work to elevate issues within public debate, policy discussions, and grassroots organizing across the continent and beyond.

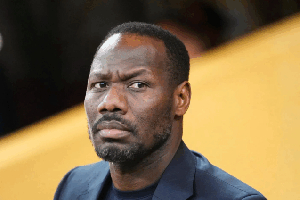

The Women and Youth Department, under the leadership of Richmond Amponsah, focuses on confronting gendered and generational injustices while building political consciousness among Africa’s largest and most marginalized demographics.

“Women have always been important to the growth, development and sustainability of any continent. Africa’s case was not different; which is why the west saw what we had and decided to destroy it by extracting the female labor force from its rightful descent. But today, we know the truth, and we will not rest until we have fought for it.”

Meanwhile, the Reparations Department, headed by Sumaila Mohammed, PPF’s blogger, anchors the organization’s work on historical redress. This department emphasizes that reparations must account for the specific exploitation and inhumane treatment suffered by the African people.

“The reality is clear: Africa owes far less than what is owed to her. Which is why this department holds in very high regards, the mantle placed upon us, to help in this fight, in our own little way. And we know, that Africa shall surely win this fight, together.”

For Mbira, African women have always resisted exploitation through survival, sabotage, care, and cultural preservation. Reparations should not be about awakening resistance but about honoring and resourcing it.

There can be no African liberation without African women’s liberation and without confronting the matriarchal debt at the heart of the Maafa. Justice must be woman-centered, or it will remain unfinished.

Reparations are far more than a backward-looking attempt to reconcile historical grievances; they are a strategic instrument for dismantling a modern global architecture that still treats human beings as disposable fuel for extraction.

True justice requires more than a mere acknowledgement of past crimes; it demands the total deconstruction of the current systems that view the global majority as tools of production rather than as sovereign economic actors.

By demanding reparations, we are not asking for a seat at a broken table; we are demanding the resources to build our own.

Opinions of Thursday, 29 January 2026

Columnist: Princess Yanney