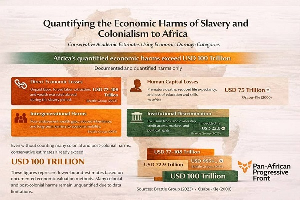

The number is as staggering as it is undeniable. A minute fraction of the harms of the trans-Atlantic slave crimes is quantified at over $100 trillion, according to a study commissioned by The American Society of International Law (ASIL), in partnership with The University of the West Indies.

According to recent econometric assessments gathered by the Pan-African Progressive Front (PPF), such estimates are the conservative economic estimate placed on the monetary value of unpaid African labor during the transatlantic slave trade alone. These numbers are not rhetorical devices; they are historical facts that demand political reckoning.

For the Pan-African Progressive Front (PPF), the conclusion of its landmark conference did not signal an end but a sharpening of purpose. What became clearer than ever was that reparations must move beyond moral appeal into structured, evidence-based economic claims. Justice, when denied for centuries, must be quantified to be enforced.

It is empirical to say, the resolutions of the Ambassadors of Pan-Africanism at the International Conference of Progressive Forces in Accra, guided by both the new political and economic roadmaps for the African continent, did not remain mere words on paper; it awakened the spirit of fighters and revolutionaries.

Central to the economic roadmap is the work of PPF’s lead economist and blogger, Sumaila Mohammed. Sumaila’s economic model for Africa does not just look at history through the lens of memory, but through the lens of mathematical loss. The recent study done by the Front categorizes the damage of Reparations into four critical categories. These damages fall under: direct economic losses such as unpaid labor and extracted wealth. Experts such as Thomas Craemer estimate the cost of this to be about USD 5.9–14.2 trillion; human capital losses resulting from premature deaths also amount to USD 75 trillion, according to Daniel Tetteh Osabu-Kle. As well as costs from stolen education, and lost skills; intergenerational harms that entrenched poverty and wealth gaps; and institutional discrimination that continued long after formal abolition, denying Africans access to land, credit, and political power, all adding up to the estimated harm cost of about $100-$131 trillion.

“I honestly believe that the task undertaken by the PPF will one day become a part of a broader framework used by the continent as a reference to gaining our Reparative justice,” said Sumaila.

Drawing from the study published on the Pan-African Progressive Front and other scholarly sources, the Front is advancing a reparations framework rooted in economic reality, not symbolism. This work insists that Africa’s underdevelopment is not accidental, but engineered through extraction and exclusion.

Speaking on the legitimacy of economic calculation in Reparations claims is Ambassador of Venezuela to Benin, Togo, and Ghana, His Excellency Jesús Alberto GARCÍA. In a discussion with the Ambassador, he expressed his thoughts on the topic and highlighted the inherent complexity of the monetary calculations of Reparations. “My initial research on the slave trade was conducted in the 1980s, and I later participated in the Slave Route Project in Benin (1994). My conclusion is that the $100 billion figure is not the only significant amount; it should also include the African knowledge that contributed to the industrial development of the West and the economies of the Americas, Asia, and Europe.”

While it is necessary to account for the economic costs of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade in the context of Reparations, it is even more important to emphasize that Reparations extend far beyond monetary compensation. The wealth, power, and global dominance of the Western world would not exist without the historical exploitation of Africa and its people. Much of what is owned, accumulated, and controlled today can be directly traced to centuries of unpaid African labor, the systematic extraction of mineral and natural resources, and the looting of priceless cultural and spiritual artifacts created by the African people.

“The reality is clear: Africa owes far less than what is owed to it,” said Sumaila as the conversation progressed. To him, the so-called debts imposed on African nations pale in comparison to centuries of stolen labor, extracted resources, and suppressed development. Cancelling these debts is not charity but a partial correction of a historical injustice.

Reparations, in this sense, are about restoring balance, freeing African economies from artificial constraints, and enabling genuine sovereignty and development on Africa’s own terms. “Africa will reclaim its right to Reparations. Although full compensation may not come in a single monetary sum, given that the value owed is threatening to the wealth of the Western world, Reparations can and must take multiple forms. One such crucial avenue is ‘Debt Cancellation’.

The Ambassador, in his concluding insights, stated, “I insist, a calculation can be made; for example, Jamaica calculated that it owed the British government approximately 21 billion pounds sterling… But Jamaica's level of self-sustaining development is three times that amount. At the Durban conference in 2001, we developed a multi-faceted reparations plan, and that plan must be reaffirmed. Next year marks the 25th anniversary of its launch. It is time to relaunch it, adding the debts incurred during the wars in Congo and other African countries. I believe the PPF can help significantly in actualizing this.”

As PPF advances this agenda, its role is becoming unmistakably clear: it is positioning itself as a continental hub for reparations research, coordination, and political strategy. With clarity sharper than daylight, the Front is aligning numbers with memory, economics with justice, and history with action.

Opinions of Friday, 26 December 2025

Columnist: Princess Yanney