Opinions of Friday, 7 November 2025

Columnist: Princess Yanney

Why natural and spiritual heritage belong in their homelands!

Heritage is both natural and cultural. The removal of Tanzania’s great Brachiosaurus skeleton and the extraction of ritual masks and reliquaries from Mali, Gabon and Cameroon reveal a pattern: scientific prestige and market value were built from colonial extraction.

Today, the British Museum houses over 73,000 African artifacts, forming an extensive collection that spans the centuries-old history and culture of Africa. There needs to be change.

Change that begins with giving back. When museums and collectors recognize the human and ecological costs behind their displays, they open a path toward meaningful repair. Restitution is a practical act of justice that rebuilds knowledge, dignity and sovereignty for source communities and nations. Restitution also reconnects people to the sources of their knowledge, spirituality and identity.

These urgent questions of justice, memory, and restitution will take center stage at the International Conference of Pan-African Progressive Forces, to be held in Accra, Ghana, from 18–19 November 2025.

The conference will also feature a special exhibition, presenting a selection that tells a story of enduring resilience as well as creativity of the African continent. While serving as a reminder to all, what has been lost and what must be reclaimed. Through this exhibition, participants will not only view historical pieces; they will engage with Africa’s true historical journey.

Objects, origin, contexts and current reality

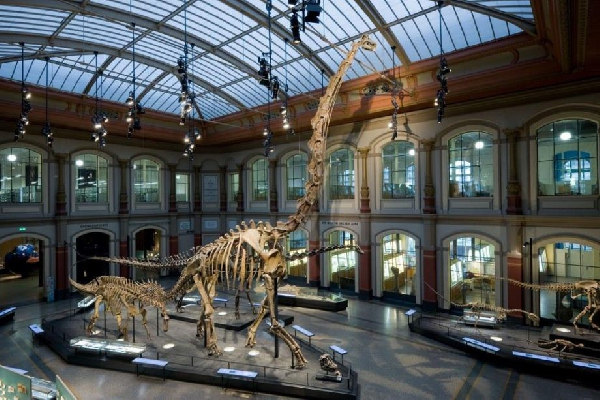

• Brachiosaurus brancai skeleton

The Brachiosaurus skeleton is one of the most spectacular and complete dinosaur specimens ever discovered. As the largest mounted dinosaur skeleton in the world, it represents the pinnacle of paleontological achievement and provides invaluable scientific data on sauropod biology and Jurassic ecosystems. For Tanzania, it constitutes an irreplaceable part of its natural heritage.

This object of immense cultural and scientific significance rightfully belongs to the land where it was unearthed. An irreplaceable piece of Tanzanian natural heritage, it was stolen to become a centerpiece of a Berlin museum, where it has remained since 1937 after its theft in 1909. Yet its grandeur cannot be separated from its origins: it remains a defining example of colonial-era extraction, when cultural and natural wealth was systematically appropriated to build prestige in the Global North. Shamefully, it is currently located at the Museum für Naturkunde (Museum of Natural History), in Berlin.

Fig.1.0 (Source; https://boasblogs.org/dcntr/the-brachiosaurus-brancai-in-the-natural-history-museum-berlin/)

• Kanaga Mask (Dogon)

Fig 2.0(Source; https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/315061)

This Kanaga mask is not just a sculpture but a vital instrument of Dogon cosmology, traditionally used in Dama ceremonies to guide the souls of the departed to the afterlife and to maintain cosmic balance. Its theft in Mali during the colonial era severed it from the sacred rituals it was created to serve. The profound injustice is that while institutions like The Metropolitan Museum accession such masks as art, the Dogon people are denied access to objects essential for their spiritual well-being. This is part of a devastating pattern where Western museums hold tens of thousands of African ritual objects hostage, disconnecting entire communities from their spiritual practices and reducing living, breathing religious artifacts to silent, decontextualized exhibits in a foreign land.

• Ngil Mask (Fang)

This 19th-century Ngil mask, a sacred instrument of justice for Gabon's Fang people, became the centerpiece of a legal drama exposing the deep injustices of the colonial art market. Stolen by French colonial governor, the mask was sold by an elderly couple for €150 at a garage sale, only to be resold at auction months later for €4.2 million.

Fig 3.0(Source; https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20220327-rare-fang-mask-sold-for-%E2%82%AC4-2-million-in-france-despite-protest-gabon)

While the couple and the dealer battle over the profits in French courts, the fundamental crime remains unaddressed: the mask's original theft during colonial rule. The Gabonese government has rightfully intervened, demanding the mask's return to its homeland and highlighting how Western legal systems continue to prioritize ownership disputes between Europeans over the restitution of looted cultural property. This case embodies the ongoing exploitation of Africa's heritage, where a sacred object of immense spiritual importance is reduced to a multi-million-euro asset, its true meaning erased by the very market that profits from its displacement. While the current location of this mask is hidden, it is, however, not forgotten. Constantly remembered by the Gabon people, as a lost heritage, yet to be recovered.

• Fang Mabea Reliquary Statue

This red wood Fang Mabea statue exemplifies the pinnacle of African sculptural artistry. Created as a guardian of ancestral relics specifically in the lands of Cameroon, it served as a spiritual vessel connecting the living with their forebears through its abstract yet powerful form.

Likely stolen during the colonial era, its transformation from sacred object to commercial commodity exemplifies how colonial extraction evolved into a lucrative global art market. Sold at Sotheby's Paris for EUR 4.35 million, it embodies the painful paradox where African heritage is valued as "art" in the West while being severed from its spiritual context in Cameroon.

This journey from sacred guardian to auction commodity underscores the urgent need for restitution, not just to reclaim objects, but to restore broken spiritual lineages and repair historical injustice.

Fig 4.0(Source; https://www.lot-art.com/auction-lots/Masterful-reliquary-Hardwood-brass-eyema-o-byeri-Fang-Mabea-Southern-Cameroon/33232765-masterful_reliquary-19.1.20-catawiki)

Conclusion

Natural heritage such as fossil skeletons are vital scientific resources for the nations that host them. Likewise, ritual objects are integral to ongoing cultural practice.

Reparations should therefore include scientific collaboration to facilitate restoring masks and reliquaries to their original communities, where they can be used and studied in their true context.

Entertainment