By Muntaka Chasant

As a backpacker and avid traveler, my adventures have included a climb to the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro and an expedition to the Mount Everest Base Camp. I have a passion not only for travel, but the chance to bring all of Ghana with me through my writing and photography. I have just returned from a few weeks enlightening journey through East-Southern Africa; my intent was to explore and familiarize myself with the human conditions on that part of the continent.

Over the course of my travels, I have seen perhaps more than my fair share of atrocities, but none compared to what I saw inside the Nyamata church in Rwanda. I have a long-held interest in the history and implications of the Rwandan genocide, and I feel deeply for the victims. So when I came to Rwanda on February 24, this year, through the northern border with Uganda, the first thing that came to mind was to pay a visit to the Nyamata memorial located in the Bugesera district, about 30km south of Kigali, the capital city. This is so I can have a far better understanding of what transpired in the 1994 genocide. Some 10,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed between April 14 and 19, 1994 in this small church.

I left Kampala, Uganda on February 23, and barely slept during the 13-hour journey, arriving in Kigali around 8:30 in the morning. After checking into a hotel, I hired a taxi to drive me to the Nyamata town, which sits on one of the thousand hills of Rwanda. Exhausted from a sleepless night, I fell asleep in the taxi and woke up in front of the Nyamata Memorial, a church that resembles a bungalow-style house, with a large garden in the front. The church interior was brightly lit by sunlight, due to thousands of bullet holes in the ceiling and doors.

The church features some relics, but primarily a harrowing insight into the genocide that transpired there in April of 1994. Similar events had occurred in the past and churches had served as refuge for the Tutsis and the moderate Hutus, but this time, things took a very different turn at this little church. Thousands of Tutsis fleeing from their homes were hiding in this church, believing they were safe. Yet the Interahamwe gained Hutu government support to massacre nearly 10,000 people at and around the Church, and used grenades to gain entry into the locked church.

Thousands of bloodstained clothes of the victims slaughtered in the church are laid on the pew. Carved in the clothing are their agonies, which stand to signify the way they were pulled to the afterlife, leaving behind painful and unbearable memories. The altar cloth still remains bloodstained. Also inside the church are displays of some of the elements used by the Hutu militia during the genocide. They include machetes, clubs, nails and all sorts of weapons. There were also government-required ID cards that tribally profiled Rwandans, specifying the ethnic group the holders belonged to. This was one of the means they used to find Tutsis.

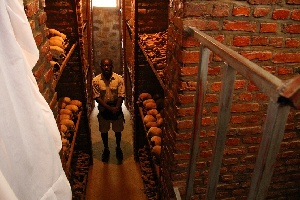

Behind the church lie crypts and mass graves, which further display the enormity of the tragedy. Filled in the crypts are skulls bludgeoned by machetes and remains of over 40,000 victims slaughtered inside the church and the surrounding area. Slowly descending into one of the crypt's claustrophobic narrow hallway, my strength started to fail me. The confronting crypt has incandescent light bulb that makes the hallway gloomy and sizzling. My eyes filled with tears as I shuddered with the haunting and depressing sight before me.

Staggering in a visceral response to what I have seen, I felt faint and my legs shook uncontrollably. My throat was dry and my heart started to beat slowly. Afraid of falling over the remains, I calmly leaned over a red brick, but not without the skulls staring right at me. We all have capacity for evil, but the atrocities inside and outside the church were beyond my understanding. I have never seen or felt anything like that in my life before.

After this short experience, I had the opportunity to interact briefly with the memorial keeper and I asked him, "What tribe do you belong to, and how did it feel at that time if you don't mind me asking?" "It's such questions that led to what you just experienced, " he responded, "we are all Rwandans now. We are not defined into tribes anymore."

There is more profundity in this short interaction than most books I have read about ethnic groups and politics in Africa. Rwandans are in the process of abandoning tribalism, but this occurred only after a million people were brutally slaughtered to this plight.

Photos are not allowed in the crypt without a permit from the government, but the keeper permitted me a rare two minutes photo opportunity after he learned I'm a Ghanaian and purposely came through Rwanda for the experience. "Go back inside quickly," he instructed, "you have two minutes - take photos and show it to your country."

This was a rare photo opportunity that many travelers did not have, but going back inside the crypt alone in over 20,000 human remains was probably the most courageous thing I have ever done in my life. The room was not well lit, so my fingers shook as I struggled with the creative mode of my SLR to find suitable settings under the low light condition.

My experience in the church was profoundly moving and gut wrenching. It brought me face to face with the evil and cruelty of mankind; savage acts conducted by my own kind. It left me sad, gloomy. I felt like a knife was stuck in my soul. It also reminded me of the importance of every human life, and why we should all challenge abuses of all kinds as soon as they come into sight.

Rwandans have suffered a great deal in life, and yet they remain strong and united. The country on one hand represents hope and the progress than can occur if there is responsible leadership. Post-genocide, the country has seen so much development and growth than most African countries I know. On another hand, it stands as a stark reminder to us all on the consequences of ethnic divisions and hatred that still permeate through most part of the continent.

It's still the Kikuyu versus the Luos in Kenya, the Lugbara versus Basoga in Uganda, the Bantu versus the non-Bantu in Angola, the Yoruba and the Igbo in Nigeria, and so on. From East, South, West and North, the entire continent is submerged in extreme tribalism. It seems that the African is forever condemned to ethnic isolation, abhorring so much hatred for other ethnic groups for no reason at all, and struggles for division over integration.

The genocide in Rwanda occurred because of deep-rooted hatred that has existed between the Hutus and Tutsis for centuries. The institutionalized division and hatred incited by this enmity eventually culminated into the genocide. Ethnic divisions and inter ethnic conflicts have become the way of life in Sub-Sahara Africa. Sadly this phenomenon has managed to glide itself into our midst. The ethnic divisions and hatred that exist in Ghana today is not any less extreme than that which existed in Rwanda prior to these atrocities. Often, we even refuse to acknowledge that it exists. But whiles we do this, we should at all time keep in mind what such level of division and hatred has caused elsewhere, like Rwanda.

Opinions of Thursday, 28 March 2013

Columnist: Chasant, Muntaka