A stronger democracy towards a better Ghana

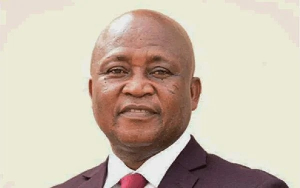

Does Ghana, in John Dramani Mahama, have a President with whom it can go places? The answer, of course, depends on where Ghanaians want to perch themselves on today’s realities. Some, it seems, cannot get their heads around the fact that Ghana does not operate in an abstract vacuum. This, often, means the failure to factor in the effects of the global economic slow-down. Having said this, much of what Ghana can hope to achieve as a nation lies in a strong democracy to complement its huge potential and resources capabilities.

Some of those ‘peppering’ Mahama seem to have forgotten that he is now a ‘president of all’ and not the flag bearer of a party. Yet the National Democratic Congress (NDC) cannot ignore the great strides made under his watch. Mahama’s handling of John Mills’ death, the open displeasure of the party’s founder, formation of a ‘sister party’ and so forth are testimony of this without drooling over the election victory of 2012. More important, he has furnished Ghana with a clear vision of how to transform its ailing system of politics into something meaningful and substantial.

From the viewpoint of democracy, the civility, humility and maturity that have engendered the peace, security and stability that Ghanaians enjoy under the Mahama administration looking over the past year or so are significant gains. Even ‘under fire’, the government has maintained this outlook as evidence that the ‘Better Ghana’ agenda is still on track. The push to narrow the ‘political gap’ and blur-out partisanship ticks the right boxes of democracy. As the administration has stated repeatedly, it is open to dialogue and collaboration on taking the country to the next level.

On the back of the humiliation and treatment meted to NDC functionaries, officials and operatives under the ‘Kuffour regime’, Mahama has naturally realised reconciliation without wasting the nation’s resources. Today, reports of the ‘political thuggery’ where politicians with the help of macho men, play ‘judge and jury’ with helpless citizens who dared to cross them, are rare. Mahama’s presidency has been resolute in its reassurance to Ghanaians that the State is not to be feared. The political process, of course, will take some time to adjust to this framework of working.

Having mounted the world stage to describe Ghana as a ‘beautiful democracy’, Mahama has challenged himself to deliver the ‘walk’ and make it a reality. Accordingly, he trusted the judiciary to do its work on the Petition amidst undertakings to accept their verdict. Although the Petitioner’s boasted of ‘guagantum’ evidence in relation to electoral malpractices, the administration took the decision to televise the proceedings in its stride. Moreover, it assured everyone that Ghana’s democracy will be strengthened by the experience which has come to past.

Instead of the politics of ‘blinding the citizenry with science’, the state’s workings are increasingly being rolled out to hone accountability. Naturally, Ghanaians have to rise above the media sensationalism and ‘fault-finding’ mentality to capitalise on this in its redefinition and refinement of political discourse. Elsewhere, Mahama has not forgotten that a president is a human being. As seen with the visit to the residence of Theodosia Okoh accompanied by Alfred Vanderpuiye owing to the National Hockey Stadium affair, his vision of democracy underlines the ‘African way of doing things’ in a marked shift from borrowed ideas.

Every country has to ‘take-stock’ of its finances in today’s economic climate. In this sense, Ghana cannot sit back as if the presidency owes it a miracle. To counter this, Mahama’s administration has been forthwith in its wisdom that ‘brilliant talk’ has to be turned into concrete actions for obvious reasons. This underpins the spirited invitation to even its staunchest critics to balance out criticism by having the solutions at hand. For Ghana, it heralds a committed drive towards a democracy that can concretise the belief that its problems are solvable, thus, giving more impetus to self-determination.

Whether Ghanaians know it or not, the ‘benevolence of the butcher’ is not driven by the interests of the dependants. Mahama, rightly so, recognises the need for Ghana to wean itself from this modus of thinking and existence. Africa, as Kwame Nkrumah advocated, must not fall for the belief that it has ‘no capital, no industrial skill, no communications, no internal markets and so forth’. A president who can crystallise the practicalities of this in today’s world remains Ghana’s only hope. One way or the other, Ghanaians cannot defy the fact that the days of wanting ‘something for nothing’ are no more.

In truth, the answer to the question under discussion comes down to a straight choice. Does Ghanaians want to run behind charlatans or true democrats with a solid grasp of what is needed to transform their nation’s fortunes? It would not harm them to look back at some of the feats of the Peoples National Defence Council (PNDC) in the 1980s to appreciate what they can do when the chips are down. Mahama, in seeking the building blocks of a stronger democracy is spot-on which with understanding, support and sacrifice is the surest route to a better Ghana.

Richmond Quarshie

Opinions of Saturday, 30 November 2013

Columnist: Quarshie, Richmond

The Mahama Touch!

Entertainment