ON 24 May 2016, I was privileged to take part in an Event held in Accra to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the passing, in 2006, of Professor Albert Kwadwo Adu Boahen, the most eminent historian Ghana has ever produced.

Now, anyone who has imbibed Ghanaian – and African – history at a deep level, would have to acknowledge that he or she is indebted to Prof Adu Boahen. What is not fully appreciated is that Prof Adu Boahen undertook, in February 1988, a task that many Ghanaians would have regarded as an act of utter “folly”.

He took on a remark made by no less a person than the Chairman of the ruling Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), Flight-Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings, in a speech at Sunyani (in April 1987) that a “Culture of Silence” had descended on the Ghanaian people.

Prof Adu Boahen, in a series of lectures given at the British Council Hall in Accra in February 1988 (known as “The Danquah Memorial” Lectures), challenged the reasons given by Rawlings for the existence of the “Culture of Silence”. He substituted those reasons with his own, which stated in strident tones that Ghana could not progress under the type of policies Rawlings and his Government were pursuing.

The “Culture of Silence”, he said, would only vanish if Ghana became a democratic society in which all national issues could be freely discussed in public without fear of reprisals against individuals who gave voice to their opinions. He was particularly scathing about the enforced disappearance of the Catholic Standard and Free Press newspapers.

Now, in my presentation at the Event held in Accra on 24 May 2016, I noted that a lot of people thought Prof Adu Boahen would be arrested as a result of the fearless critique he had made of the policies of the PNDC, during his Danquah Memorial Lectures. Prof Boahen himself must have been aware that he could have been picked up and subjected to harassment for being so frank about the failings of the PNDC.

Yet the Prof did not baulk at what he considered to be his duty to the people of Ghana, and had clearly outlined the sort of policies which he said were the only way of killing the “Culture of Silence.”

Having done that, Adu Boahen then did something even more astounding: he decided to contest against Rawlings in the presidential election that was held in 1992 (subsequent to the adoption of a constitution that was to bring democracy back to Ghana.) Adu Boahen stood against Rawlings, knowing fully well that it was possible for Rawlings to use violent methods to disrupt his election campaign, or put other obstacles in his way. How (I asked in my presentation) was Adu Boahen able to muster the courage to stand against Rawlings when he must have been aware of such possibilities?

The answer I gave to my own question was that Prof Adu Boahen must have been inspired by some of the characters he had studied and written about in history. One character who came readily to mind was Nana Yaa Asantewaa, Queen Mother of Edweso, who led the Asante army against a British expedition that was armed with cannon guns, which invaded Kumasi in March 1900.

The men of Asante stood by, timidly, as the British Governor of the God Coast, Sir Frederick Hodgson, asked the Asante nation to produce to him, its most sacred artefact – the famous Golden Stool!

This was a great insult to the Asantes because they fervently believed that the “soul” of the Asante nation had been implanted into the Golden Stool by Okomfo Anokye, “who had commanded it to descend to the earth – from the sky – by magical means! If it left Asante, the Asante nation would become defunct.

Yaa Asantewaa asked the Asante men: “Are you going to sit down and allow these white men to take the Golden Stool away too after they have arrested and deported our King, Nana Prempeh (The First) to the Seychelles Islands? If you men won't fight, me and my fellow women will fight the British!” Thus began the “Yaa Asantewaa War,” which constitutes one of the most glorious chapters not only in Ghanaian history but African and – indeed – world history.

If Boadicea (of Great Britain) is well known in world history, why hasn't Yaa Asantewaa too become a major figure in world history? Prof Adu Boahen tried to correct that in his contribution to the prestigious UNESCO History of Africa.

In studying this episode (and Prof Adu Boahen went to the Seychelles personally to carry out research on Nana Yaa Asantewaa and the other Asante royals who were deported there) the Prof must have asked himself, “What at all impelled this woman, Yaa Asantewaa, to do what she did?”

And in answer to that, he must have told himself, “If Yaa Asantewaa could summon the courage to fight Sir Frederick Hodgson and his cannon guns, come what may, then I too must summon the courage to fight the 1992 presidential election against Flight-Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings, come what may!”

And he did precisely that – with the result that even though he lost against Rawlings, his New Patriotic Party eventually gained power under President J A Kufuor, and ushered Ghana into what is now a free and democratic country, with – if anything – a “Culture of Loudness”, not a “Culture of Silence!” In my presentation, I noted that it wasn't Prof Boahen alone who had been inspired by Yaa Asantewaa, but that when I was growing up at Asiakwa, I had heard the women of the town sing, during mmommome cultural rites they performed to summon the spirits of their ancestors to protect their sons who were fighting for the British (sic) in far-away Burma and East Africa, during the Second World War – sing a song about Yaa Asantewaa.

The song went like this: Konkrohinkoo, Yaa Asantewaa eei, ?baaa basia a ?ko apr?m ano eei, Yaa Asantewaa.

And to the amusement of the gathering, I foolishly began to sing the song, in my croaky “frog's voice”! My attempt, though not very successful, nevertheless spurred a lady in the audience to take up the song and sing it properly: it became, probably, the most bizarre duet ever sung at a public gathering in the annals of musical history!

In resisting the fear of making a fool of myself and singing the song, I had thus inadvertently provided proof that indeed, there was such a song. What made it even more remarkable was that the women of Asiakwa who had sung it to my hearing were Akyem women, who were not won't – normally – to sing anything in praise of an Asante woman! Because, of course, the history of relationships between Akyem and Asante had been marked by a great deal of internecine blood-letting.

Now, I thought I had heard the Asiakwa women say “konkrohinkoo!” – a word I did not understand but passed off as an anachronism that had vanished from the language.

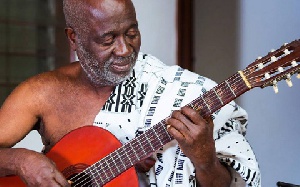

But one day, I came across, on Youtube, a song Agya Koo Nimo had composed about Nana Yaa Asantewaa. The song is called Efie ne fie. And in it, Agya Koo Nimo (who, by the way, was brought up at the court of the King of Asante, Manhyia Palace, and who used, as a child, to listen to the songs sung by the women of the court) rendered the authentic lyrics as:

?koo 'Hen ko eei! Yaa Asantewaa eei, ?baa basia a ?ko apr?m ano eei Woay? bi agya y?n ooo!

Now, this makes perfect sense, for ?koo 'Hen ko literally means: “She fought a King's War” (i.e.: Yaa Asantewaa, a “mere woman”, fought like a King!) I am in the irredeemable debt of Agya Koo Nimo for putting me right about this word which my child's ears had heard and not been able to properly grasp – konkrohiikoo!

Left to me alone, Koo Nimo (now a good 83 years old) would be granted a life pension by the Asanteman Council for enshrining the great deeds of Asante history and Asante cultural practices in beautiful songs – not because he needs the money, but because it is a good thing per se to reward talent, in order to encourage others to use their talent in the service of their nation.

For if Agya Koo Nimo has set me right, he will set others, too, right with his music. He's done it in a permanent, ineradicable form, out of love for his cultural roots. The whole nation ought to be proud of someone who has taken the trouble to learn – and teach others – about how great Africa is.

Opinions of Tuesday, 28 June 2016

Columnist: Cameron Duodu