By Kwarteng, Francis

We need to celebrate our cultural ambassador and heroes of highlife and palm win music

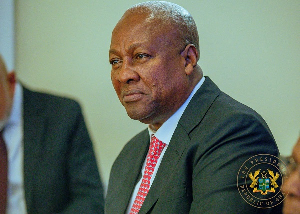

Yet, after all is said and done, we cannot but commend President Mahama highly for extending material and financial assistance to veterans of the entertainment industry, men and women who promoted Ghanaian culture across Africa and the rest of the world.

We do not care if the president is doing this for political expedience.

These men and women did so much for Ghanaian, African and world music without making money in the process—except a few like Osibisa’s Kiki Gyan who made millions.

These men and women would have been millionaires if they lived in the West. We are not saying music should be exclusively about monetary expectations. Yet they deserve (d) every single dollar the world owes them.

Just listen to Alex Konadu (“One Man Thousand”)’s polyrhythmic guitar screaming, whining and crying on such powerful classics as “Asem Bi Adi Bone,” “Agyatu Wuoye,” “Asianawa,” “Asaase Asa,” “Owuo Mpe Sika,” “Yare Ama Masei,” “Owuo Na Esee Edee,” “Nsadwaase,” “Odo Ani Nisuo Waa,” “Good One”…

Of course, one cannot listen to Konadu’s “Asaase Asa” and “Agyatu Wuoye” and not feel the intellectual weight of a serious philosopher dig into the depths of eschatology and not feel the gripping pangs of critical emotionalism on the human heart and a heightened sense of intellectual, philosophical and cultural clarity as well as of emotional forthrightness, both the latter two position views on the part of Konadu.

On “Agyatu Wuoye,” for instance, he made a direct reference to what Samuel Owusu had referred to as “Abusua Kyiri Ka,” perhaps one of the latter’s most popular titular tracks, while also lamenting the Abusua’s unbridled love for the dead rather than for or at the expense of the living, an unresolved conundrum in our culture.

Perhaps one of Konadu’s most insightful rhetoric or philosophical lyrical best was when, on “”Agyata Wuoye,” he drew a striking imagery comparison between the eschatological finiteness of man and that of the flora world, plants (statements which we loosely translate into English here):

“Man is nothing…put cocoyam in the soil and it is cocoyam that germinates…put plantain in the soil and it is plantain that germinates…put cassava in the soil and it is cassava that germinates…but when man is buried or put in the ground that is the end…it is as though the entire earth is used up…the earth is really having fun, enjoying itself to the fullest…the inside of a coffin is hot.”

Yes, the earth is indeed God-king. It decides who lives by virtue of the intrinsic character of regenerative or resurrectional potentiation—that is, who enjoys a continuity of life or existence.

Yes, we pollute the earth, we abuse the earth, we harm the earth, we spit and urinate on the earth, we curse the earth—yet it is also the final arbiter of the tensions between life and death.

Or to that of George Darko’s guitar on “Ako Te Brofo” and on all the tracks on “Hilife Time” and “Moni/Money Palava” albums…Or to Dr. Paa Bobo talking- and whistling-guitar on “Nsem Keka” and “Enye M’ani A” and “Asobro Kyee” and “Abaa Saa”…

Or to the sinusoidal guitar riffs on Atakora Manu’s “Otete Mpomamu”…

Or to Guy Warren’s polyrhythmic syncopated drumming…

Or to Kiki Gyan on keyboards…

What happened to the lyrical subtlety and rhythmic richness of A.B. Crentsil’s “Adam & Eve”?

And, one will certainly come to terms with the fact that he or she is dealing with some of the world’s most influential geniuses in the history of music.

We remember Dr. Paa Bobo, a profound lyrical raconteur, learning how to play guitar from one of the nation’s guitar virtuosos, Smart Nkansah, and consequently turning out to be guitar virtuoso and a prolific musician himself.

What is more, another guitar virtuoso who goes by the name Koo Nimo even served as a Professor of Ethnomusicology in some American universities where he taught how to play guitar to his American students and some professional American musicians.

One Andrew Laurence Kaye, a Columbia University student, was awarded a doctorate (Ph.D) for his dissertation, titled “Koo Nimo and His Circles: A Ghanaian Musician in Ethnomusicological Perspective (1992).”

Prof. Kaye then provides the following insights into Koo Nimo and his social world of music as part of his dissertation abstract (go to the end of this essay for additional information on the abstract):

“This dissertation offers a social biography and ethnomusicological assessment of Daniel Kwabena Boah Amponsah, known as "Koo Nimo," a contemporary Ghanaian musician, ensemble leader, educator, and union activist…”

For instance, Scottish-born New Zealand author, arts educator, journalist, and broadcaster wrote the following about Kiki Gyan in the article “Kiki Gyan (1957-2004): From Dance Floor To Death’s Door”:

“Apparently Kiki Gyan was once voted the eighth best keyboard player in the world —during his Osibisa stint I guess—and he’s certainly got plenty of music ripe for sampling.”

These highly gifted musicians and their music evoke strong emotions in some of us even to the point of sobbing.

Why these men and women will or should die is beyond our comprehension!

Even more interestingly, many of the older generation of musicians, singers, songwriters, and performers were/are better lyrical poets than those of the hiplife generation.

The hiplife generation forgets that the technique of rhyming lyrics, for instance, is not unique to hip hop music (rap music) and hiplife.

Andrew L. Kaye's dissertation abstract on koo nimo

“This dissertation offers a social biography and ethnomusicological assessment of Daniel Kwabena Boah Amponsah, known as "Koo Nimo," a contemporary Ghanaian musician, ensemble leader, educator, and union activist.

“Chapter 1 discusses the ethnomusicological structure into which Koo Nimo enters, with emphasis on the indigenous musical heritage of the Akan region of Ghana, and the evolving musical heritage arising from Ghana's contact with Anglo-European mercantile, political, and cultural influence in the early 20th century.

“Chapters 2 through 5 focus on Koo Nimo and discuss, in diachronic sequence, his familial and ethnoeconomic background, the development of his interests in music, his decision to make a career as a technician in science and a "part-time" career as a musician, and the development of his musical style and reputation as a performing artist, within the context of Ghana's larger musical and socioeconomic development.

“Chapter 6 continues this chronology, but with an emphasis on Koo Nimo's participation as musicians' union president, and as a musical activist within Ghana's tumultuous economic and political readjustments in its most recent history.

“Chapter 7 isolates Koo Nimo's musical style for an extended, and essentially synchronic treatment. Koo Nimo's musical repertory is analyzed according to a six-part plan, treating first his preferred instrumental and sonic choices, then the characteristic rhythmic, harmonic, and melodic constructions he employs, and finally lyrics and the act of performance itself, as critical elements in Koo Nimo's musical-performative world.

“The concluding chapter summarizes the overall nature of Koo Nimo's complex circle of social and musical interaction, patronage, and public support, as it exists in Ghana and a widening international context, summarizes the place of Koo Nimo's musical style within the evolving context of Ghana's changing musical world, and isolates some of the original contributions Koo Nimo has made as an individual musical craftsmen.

“It is also suggested that, with historical distance, we will be able to more clearly see Koo Nimo, as a musician, creative stylist, and activist concerned with tradition, change, and the proprieties of Ghana's musical structure, within the greater comparative perspective of contemporary musicians in a changing black Africa, and more generally, in the modernizing third world.”

Special note

Prof. Kaye has formerly taught at Lehigh University. And he is currently an ethnomusicology professor/music educator at Montclair State University (New Jersey) and Columbia University (New York)

Document URL: http://search.proquest.com/docview/303959485 (Note: We believe readers can purchase a copy of this dissertation from this link).

For more information, please visit the website http://music.columbia.edu/contact-us

Reminder

We shall return with Part 7.

References

Ghanaweb. “Pastor Larbi Is A Liar Dark Suburb.” August 27, 2016.

Ameyaw Debrah. “Ghana Gets A Rock Band, Faint Medal.” May 27, 2012. Retrieved from http://ameyawdebrah.com/ghana-gets-a-rock-band-feint-medal/

Ghanaweb. “Compose good songs—Agya Koo Nimo.” May 31, 2016.

Modernghana. “Rex Omar—Ghana’s Most Exciting Musical Export.” June 3, 2007. “The Spectator (Jonathan Gmanyami).

Graham Reid. “Kiki Gyan (1957-2004): From Dance Floor To Death’s Door.” May 30, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.elsewhere.co.nz/absoluteelsewhere/5682/kiki-gyan-1957-2004from-dancefloor-to-deaths-door/

Opinions of Sunday, 11 September 2016

Columnist: Kwarteng, Francis