Introduction

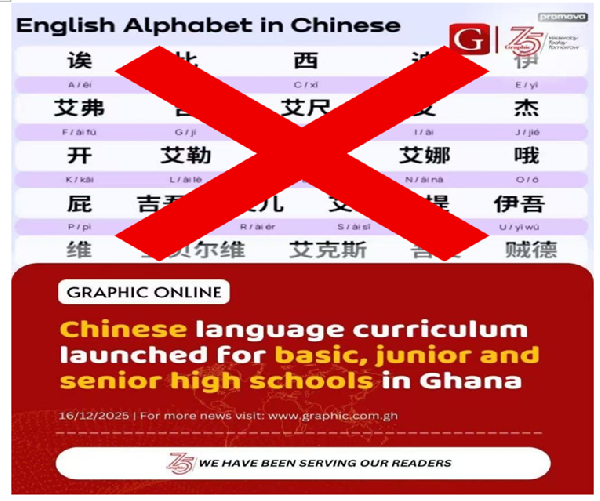

Daily Graphic Online’s recent publication on the launch of Ghana’s new Mandarin Chinese curriculum has drawn attention after a flyer accompanying the report inaccurately presented “English alphabets in Chinese.”

The flyer, designed and circulated by Graphic Online, appeared alongside coverage of the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment’s (NaCCA) introduction of a Mandarin Chinese language curriculum for primary, junior high, and senior high schools in Ghana.

The curriculum was officially launched by Prof. Vincent Assanful, Chairman of the NaCCA Board, who represented the Director-General, Prof. Samuel Ofori Bekoe.

The launch formed part of activities marking the 10th Anniversary of the Confucius Institute at the University of Cape Coast (CI‑UCC) and the 2025 Chinese Ambassador’s Awards ceremony, held on December 16, 2025.

The event brought together education stakeholders, traditional authorities, diplomats, and academics.

Following the publication, the attached flyer was widely shared across social media platforms. However, a review by the Sino‑Ghana Research Center for West Africa (SGRC-WA) and School of Foreign Studies and Trade (SFST) at Hubei University of Automotive Technology (HUAT) in Shiyan City, China, has identified major inaccuracies in the depiction of what was described as “English alphabets in Chinese.”

The SGRC-WA has therefore issued a clarification and intends to correct the errors to ensure accurate public understanding of the Chinese language and its writing system.

Figure 1: The incorrect image pairing English letters with supposed Chinese characters.

Source: Daily Graphic Online (2025).

Phonetics and phonology of Mandarin Chinese

For English speakers, language learning usually begins with the alphabet. Letters carry sound, and once you know the alphabet, you can roughly predict how English words are pronounced.

So, when a viral image pairs English letters with Chinese pronunciations—诶 (A)、比 (B)、西 (C)—and suggests this is “how to learn Chinese,” it feels intuitive. It is completely wrong. It only fits the English way of thinking.

To understand why, we need to start with simple questions: How does Chinese actually work as a language? If Chinese does not use letters to represent sound, how do people learn to pronounce it?

Mandarin Chinese is built on two distinct yet interconnected systems: the writing system (characters) and the sound system (syllables) developed in a system called Pinyin.

Pinyin is the phonetic notation system that writes sound using Latin alphabets. It is not the alphabet of Chinese. To improve literacy, promote Mandarin and support language teaching, Chinese and foreign scholars proposed various phonetic systems from 19th Century to 1940s including special symbols (e.g.ㄅㄆㄇㄈ) to mark pronunciation and Latin letters (e.g. uo→我 ) to write Chinese. These early attempts paved the way for the creation of Pinyin.

In the 1950s, China formed a language reform committee and began working on a new, scientific, unified, and easy-to-learn phonetic system. In 1958, the official Pinyin Scheme was released.

Figure 2: Pinyin Schemes development and adoption.

Source: Fen (1958).

In 1982, the Pinyin Scheme was adopted by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO 7098). After undergoing two major revisions, ISO, in December 2015 officially published ISO 7098:2015 as the current official romanization system for Chinese.

It has become an essential tool for learning Chinese worldwide and it is recognized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). It is the bridge between Mandarin Chinese Characters and pronunciation.

Let’s take some practical examples to relate the Pinyin system to the information in the image presented by Daily Graphic Online. 西 in the mentioned image means west, In oracle bone script, the character xi (西) is a pictograph whose original meaning refers to birds resting. 开 means open. The original meaning of kai (开) is ‘to open a door’. The Chinese character 明means bright.

The original meaning of the character ming (明) is ‘illumination,’ while ‘brightness’ is an extended meaning, which is formed by combining two meaningful components: 日 (sun) and 月 (moon). Characters carry meaning through structure, not through phonetic spelling.

Mandarin Chinese pronunciation is based on syllables, not letters. Each syllable consists of initial (the starting consonant), final (the main vowel), and tone (the pitch pattern that changes meaning). The character 西 corresponds to one Mandarin syllable—initial: x, final: i, and tone: ¯ (first tone). So, the syllable is xī.

It follows the notation system used in Huang–Liao (2017:64), or alternatively one may use the five‑degree marking system or mark tone values directly. X is closer to the sh in she. The pronunciation of x doesn’t change anytime. i always sounds like the ee in see. The tone is ¯, the first tone, a steady, high pitch. A syllable represents the actual sound of the character.

If there’s one feature of Mandarin that reliably surprises learners, it’s tone. In English, tone is emotion; in Mandarin Chinese, tone is meaning. The same pinyin spelling xi can split into four entirely different words simply by changing the tone. With a high, steady tone, xī (西) means west.

Tilt it upward into xí (习), and it becomes to practice or to study. Dip low and rise with xǐ (洗), and it means to wash. Drop sharply to xì (细), and now it means thin or detailed.

Linguistically, they share the same syllable structure: x + i. Visually, they share the same pinyin spelling: xi. But shift the tone, and the meaning flips entirely.

In Mandarin Chinese, tone isn’t decoration — it’s part of the word. Same letters, different tones, completely different meanings. The syllable xī is the sound.

The pinyin xī is the written form of that sound. Characters carry meaning, syllables carry sound, and pinyin is the written guide to that sound. Together, they form the full structure of the Mandarin Chinese language.

That image pairing English letters with supposed Chinese characters offers a useful reminder: in language learning, misinformation is far more damaging than difficulty itself.

English speakers never learn their alphabet through Chinese sounds, and by the same token, Mandarin Chinese language should not be introduced through playful but fundamentally inaccurate pairings of English letters and Chinese characters.

A national policy that encourages people to learn Mandarin is unquestionably valuable. It opens doors to cultural understanding and global communication. Yet oversimplifying Mandarin Chinese into a quirky alphabet chart does not make the language more accessible.

The image strings together a jumble of incorrect Chinese characters to “voice” English letters, creating something that looks less like language learning and more like a bizarre novelty item. It distorts how languages actually work. Languages are not decorative accessories; they carry cultural memories, historical depth, and distinct ways of understanding the world.

Inviting the world to learn Mandarin is a cultural opportunity. However, misleading the public with shallow, inaccurate shortcuts is a cultural setback. In an age where misinformation spreads faster than facts, the media has a responsibility not just to entertain, but to uphold clarity, accuracy, and respect for the languages and cultures it portrays.

The SGRC-WA at HUAT in Shiyan City, China, remains committed to deepening cultural and educational collaboration between Ghana and China. We are dedicated to supporting high‑quality Chinese language teaching and learning through research, capacity building, and sustained institutional partnerships.

In line with this mission, we operate an open‑door policy and welcome engagement from stakeholders, news editors, educators, and all interested individuals or organizations seeking guidance or assistance on Chinese language education in Ghana.

Contacts:

Website: www.sgrcwa.huat.edu.cn

Email: infosgrcwa@huat.edu.cn

Office line: +86 719 851 2306

Mobile number: +86 135 9785 0330

Address: Room 3505, Hubei University of Automotive Technology, 167 Checheng West Road, Shiyan City, Hubei, China

References

Daily Graphic Online (2025). Chinese language curriculum launched for basic, junior and senior high schools in Ghana. Daily Graphic Facebook Page

Fen W. (1958). Chinese Pinyin Program. Beijing, China: Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China.

Huang, B., & Liao, X. (2017). Modern Chinese. Beijing, China: Higher Education Press.

International Organization for Standardization (2015.) Information and documentation— Romanization of Chinese (ISO 7098:2015)

Zhou W. (2022). Elementary Chinese I. Michigan: Michigan State University Library.

Contributors:

Prof Rongguang Yang, Provost, SFST, HUAT

Prof Sun Yuan, Associate Professor, English Department, SFST, HUAT

Prof Min Zuchuan, English Department, SFST, HUAT

Dr Lemuel Gbologah, Director, SGRC-WA, HUAT

Dr Gabriel Asante, Research Fellow, SGRC-WA, HUAT

Opinions of Saturday, 3 January 2026

Columnist: Sino-Ghana Research Center for West Africa (SGRC-WA)