Opinions of Friday, 18 April 2025

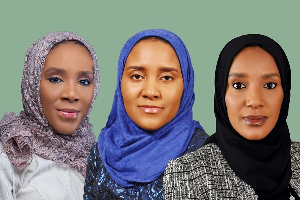

Columnist: Naziha Gombilla Amin and Martin Waana-Ang, Esq.

An Appraisal of Ghana's Environmental Protection Act, 2025: Bridging law and climate action

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent times, the world has grown increasingly concerned about the negative impact of greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) on our planet’s delicate ecosystem. Carbon dioxide emissions driven by energy consumption, deforestation, pollution, and biodiversity loss have garnered critical attention, particularly in light of the persistence of climate change, which has occasioned a number of attempts to see to the reduction of such emissions. Ghana grapples with the challenges posed by rising GHG.

To address these concerns, Ghana enacted a comprehensive legal framework, the Environmental Protection Act, 2025 (Act 1124) to replace the Environmental Protection Act 1994 (Act 490) with its objective of advancing climate action and promoting sustainable development.

The aim of this article is to explore how the EPA ACT advances Ghana’s efforts at mitigating climate change and her participation in the Carbon Market, Challenges in the implementation and the way forward. Act 1124 represents a significant step forward in Ghana's efforts to address climate change, introducing several innovative provisions for mitigation, adaptation, and participation in carbon markets.

2. OVERVIEW OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION ACT, 2025 (ACT 1124)

Ghana has gone through several phases of climate response development since ratifying the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1995. The Ghana National Climate Change Policy 2013 is Ghana’s integrated response to Climate Change and outlines its vision as ensuring a climate-resilient and climate-compatible economy while achieving equitable low-carbon economic growth.

Under the Paris Agreement, which Ghana ratified in September 2016, Ghana committed to the reduction of GHG emissions and building resilience against the negative impacts of climate change. The EPA Act thus serves as a legislative framework to institutionalise and streamline Ghana’s climate efforts, aligning national policies with international efforts to limit global warming to 1.5℃ by 2050.

The new Environmental Protection Act 2025 (Act 1124), enacted on 6th January 2025, replaced the Environmental Protection Act 1994 (Act 490). The aim of Act 1124 is to amend and consolidate laws relating to environmental protection, and to establish an Environmental Protection Authority.

The Act makes provision for pesticide control and regulation, the control, management and disposal of hazardous waste and electrical and electronic waste and also provides for the co-ordination of climate change responses and for related matters.

Additional enforcement powers have been conferred on what used to be the Environmental Protection Agency to the Environmental Protection Authority beyond the mere issuance of environmental permits. Innovative mechanisms geared towards emission reductions, strict compliance measures have also been incorporated into Act 1124.

Act 1124 further provides a legal foundation for carbon trading through the Establishment of the Carbon Registry and a carbon market committee. By strengthening regulatory oversight, bolstering Ghana’s climate financing framework, the Act aims to ensure that Ghana is on track to meet its climate commitments as provisions in Act 1124 aligns with global best practices.

3. CLIMATE CHANGE MITIGATION AND THE EPA ACT

To position Ghana as an innovative leader in the global fight against climate change, The EPA ACT, provides a robust legal framework by implementing policies and strategies geared towards mitigation and adaptation aspects of climate change. PART 5 of the Act centers on strengthening Ghana’s climate change governance.

One way is through renewable energy promotion. The Environmental Protection Authority have been empowered to lead efforts to promote low carbon development. This is through the reduction of GHG emissions in primary sectors such as Oil and Gas (Energy), Agriculture and Refrigeration. This is discernible in Section 146.

The EPA has been mandated to explore meaningful collaborations with local, national including the Ministry of Energy and international institution to scale up renewable energy and energy efficiency programs. By the prioritising low-emission development, Ghana aims to transition to a greener economy while maintaining economic growth.

To curb emissions generated from waste, the Act introduces sustainable solutions to assist in the disposal of hazardous and electronic waste. Act 1124 imposes strict regulations on importing and exporting hazardous waste, including electric and electronic equipment and waste. These measures adopted by the Act supports climate mitigation through the reduction of GHG emissions such as Methane and Carbon dioxide.

By strictly regulating importation and exportation of hazardous waste and further extending this to electrical and electronic waste, the Act prevents Ghana from becoming a dumping ground for emission wastes from developed countries and supports Ghana’s commitments under the Paris agreement to contribute to a low carbon economy.

The Act recognises that issues pertaining to climate change affects all sectors of the economy and not an isolated environmental issue. Accordingly, Section 144 mandates the mainstreaming of climate change responses into national, sectorial and district levels. This ensures that issues related to climate action are embedded in governance and decision making processes.

Further, Section 145 of the Act enhances adaptive capacity by supporting adaptation plans that would enhance the resilience of our eco systems, coordinating efforts amongst the government agencies, private sector organisations and civil society to strengthen the country’s ability to cope with climate impacts like floods and droughts.

The Act further provides for the proper implementation of Climate Change measures namely, the facilitation of stakeholder engagement, public awareness campaigns, the fostering of national dialogues on climate action and capacity building across all sectors.

4. THE CARBON REGISTRY AND CARBON MARKET UNDER ACT 1124

A significant step in Act 1124 is the creation of the Carbon Markets and Climate Finance Mechanisms, the Carbon Registry, the Carbon Market Committee and the Mitigation Fund all of which are geared towards supporting carbon pricing.

The Act establishes a regulatory framework for Carbon Markets in Ghana. The Carbon Market Committee has been tasked with the function of setting the standards and approving methodologies for mitigation projects that qualify for International carbon Trading and that Ghana’s Carbon Market aligns with global best practices particularly under the Paris Agreement. The Carbon Market Committee has then been assigned the mandate to make recommendations on how funds are to be allocated to achieve the country’s mitigation goals.

The Carbon registry is meant to play the imperative role of tracking the transfer of internationally transferred and Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOS) and the provision of public access to information on mitigation activities.

To support efforts towards Mitigation, the Mitigation Fund has been established by the Act geared towards funding climate change mitigated initiatives. The object of the fund is to provide support for bilateral cooperative mitigation projects, drive investments geared towards emission reductions and the scaling up of low carbon activities.

As a party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Ghana is committed to transparent reporting on Climate Action and the EPA is meant to coordinate and prepare submissions of Ghana’s Climate Change Reports, geared towards ensuring that Ghana meets its obligations under Global Climate Agreements.

Additionally, powers have been granted to the EPA to enact regulations that would ensure climate resilience, carbon trading, adaptation and green technologies.

5. CHALLENGES IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF GHANA’S CLIMATE ACTION STRATEGIES

Ghana, as a nation highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change due to its reliance on climate-sensitive sectors like agriculture, energy, health and water resources has demonstrated a commitment to addressing this global challenge through the ratification of international agreements such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement.

While the enactment of the Environmental Protection Act, 2025 (Act 1124) signifies a crucial step towards institutionalising and streamlining the country’s climate efforts, several challenges exist that may significantly hamper its effective implementation. Thus, Ghana continues to face a multitude of interconnected challenges in the effective implementation of its climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies.

One of the most significant and frequently cited difficulties is the inadequacy of funding for climate change programmes and projects. Research reveals that Ghana’s initial Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) targets were conditional on receiving international support, including financial resources, technology transfer, and capacity building. While some progress has been made, financial constraints have slowed down the anticipated outcomes in key areas like renewable energy development and the Ghana Cocoa Forest REDD+ Programme.

The sheer scale of investment required to implement Ghana’s climate action measures, estimated at US$22.6 billion for the period 2020-2030, stands in stark contrast to the limited national budget contribution and the country’s high public debt levels. This financing gap severely hinders the implementation of both mitigation and adaptation measures across various sectors.

While Act 112A has created a Fund from which climate action related activities would be funded, this is not novel in Ghana as there are so many Acts of parliament that established similar dedicated Funds in theory, but in practice, these funds, are never populated.

To address this challenge, the regulatory framework needs to prioritise mechanisms for enhanced climate finance mobilisation. This could involve:

(a) Establishing clear legal mandates and incentives for public-private partnerships (PPPs) in climate-resilient infrastructure and sustainable projects. The government could leverage on the Public Private Partnership Act, 2020 Act 1039 to enact specific regulations outlining the roles, responsibilities, and risk-sharing mechanisms for PPPs in renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, and waste management.

(b) Developing a robust legal and regulatory framework for green bonds and other innovative financial instruments to attract both domestic and international private sector investment.While the Securities and Exchanges Commission (SEC) has issued some directives regarding green bonds and conditionalities for investment in same, we believe that legislation defining the criteria for green projects, reporting requirements, and investor protections would be essential to provide a clear regulatory pathway.

(c) Strengthening the capacity of national institutions to access international climate finance through dedicated legal provisions that support the development of bankable project proposals and compliance with international funding requirements.

Beyond financial limitations, Ghana grapples with challenges in policy implementation and weak enforcement of existing environmental regulations. Despite the formulation of numerous climate change policies, strategies and plans, including the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (NCCAS) of 2012 and the National Climate Change Policy (NCCP) of 2013, their effective implementation has been hampered by a lack of political will and inadequate resources for enforcement.

The predominantly policy-based climate legal regime, prior to the new EPA Act, lacked the legally binding force necessary for consistent and comprehensive action. To overcome this, the regulatory framework should focus on strengthening the legal basis for climate action and enhancing enforcement mechanisms:

(a) The new Environmental Protection Act, 2025 (Act 1124), which provides a more robust legal framework, needs to be fully operationalised with clear regulations and guidelines for its implementation across all relevant sectors. This includes defining specific duties and responsibilities of various government agencies and stakeholders in climate action.

(b) Establishing clear legal sanctions and penalties for non-compliance with climate-related regulations, ensuring that these are consistent. This might require amendments to sectoral laws or the development of specific environmental offences and enforcement procedures under the EPA Act. It is also suggested that a specialised environmental court be dedicated to the trial and adjudication of climate and environmental related offences to expite the process.

(c) Legally mandating regular monitoring and evaluation of climate policy implementation at national and sub-national levels, with transparent reporting mechanisms to ensure accountability. This could involve incorporating specific monitoring and evaluation requirements within the regulations accompanying the EPA Act.

Another critical difficulty lies in the limited technical capacity and expertise within Ghana to effectively address climate change mitigation and adaptation. This constraint affects various aspects, including the development and deployment of renewable energy technologies, participation in complex carbon markets, the formulation of innovative financial solutions, and the integration of climate considerations into sectoral planning.

The mining sector, for instance, highlights a need for more trained workers to handle low-carbon technologies. To address this, the regulatory framework needs to prioritise capacity building and knowledge transfer:

(a) Enacting legislation that mandates and funds national climate change capacity-building programmes targeting government agencies, the private sector and local communities.This could involve establishing dedicated training institutions or incorporating climate change education into existing curricula.

(b) Creating legal frameworks that facilitate technology transfer and the adoption of climate-friendly technologies through incentives, research and development support, and partnerships with international institutions. This could involve specific provisions within the EPA Act or related regulations that promote the import and local development of clean technologies.

(c) Formalising the Ghana Climate Ambitious Reporting Programme (G-CARP) through legal means to ensure consistent data collection and reporting by line ministries, thereby supporting informed decision-making and capacity development needs assessment. This could be achieved by incorporating the G-CARP framework into regulations under the EPA Act.

Weak institutional coordination among various government ministries, agencies and departments also represents a significant impediment to a coherent and effective climate response. The cross-sectoral nature of climate change necessitates seamless collaboration; however, existing structures often suffer from a lack of clear mandates, overlapping responsibilities, and inadequate communication. The establishment of the National Climate Change Committee (NCCC) and Climate Change Units within key ministries are positive steps, but their effectiveness needs to be underpinned by a strong regulatory framework that clarifies institutional roles and fosters inter-agency collaboration

(d) Developing a comprehensive legal framework that explicitly defines the roles and responsibilities of different government entities in climate change mitigation and adaptation, including mechanisms for inter-ministerial coordination and information sharing.

While Act 1124 has designated the Environmental Protection Authority as the body in charge of overseeing climate action activities in Ghana, the Act is curiously silent on the role other regulatory bodies play in this regard. The Act merely provides that the Authority should colloborate with other government institutions.

The extent of collaboration is not defined and the extent of the mandate of the other regulatory bodies particularly, the Securities and Exchanges Commission and the Bank of Ghana are not clearly delineated. This collaborative gap is particularly worrying considering the potential for conflationary regulations. It is therefore suggested that the law make clear prescriptions of the roles of the various regulatory bodies of government to ensure efficient regulation. This could be a key component of the operational regulations under the EPA Act.

(e) Establishing legal mandates for joint planning and implementation of climate actions across relevant sectors, ensuring that climate change considerations are integrated into sectoral development plans. This might require amendments to sectoral planning laws to explicitly include climate change integration requirements.

The lack of comprehensive and reliable data on climate change impacts, GHG emissions, and the effectiveness of mitigation and adaptation measures poses another substantial challenge. This deficiency hinders informed policy formulation, effective monitoring and evaluation, and transparent reporting under international agreements.

While Ghana has made efforts to fulfill its reporting obligations to the UNFCCC, the national monitoring and reporting system needs strengthening to cover a broader range of data and ensure accuracy and consistency. The regulatory framework needs to mandate and support robust data collection and management systems:

(a) Enacting legislation that requires relevant entities in key sectors to regularly collect and report sector-specific climate-related data in a standardised format. This could be mandated through regulations under the EPA Act, specifying the types of data to be collected, reporting frequencies, and responsible entities.

(b) Establishing a national climate change data management platform with clear legal provisions for data accessibility, quality control, and utilisation for policy and research purposes.

(c) Strengthening the legal mandate and resources of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to coordinate national GHG inventories and other climate change reports, ensuring compliance with international reporting requirements.

Prior to the enactment of the EPA Act 2025, Ghana’s climate legal regime was characterised by a patchwork of policies rather than a dedicated climate change law. While these policies provided guidance, they lacked the legal force necessary for consistent implementation and long-term certainty.

The new EPA Act represents a significant step towards addressing this gap by providing a more comprehensive legal framework. However, the regulatory framework still needs to ensure that climate change considerations are effectively integrated into all relevant sectoral laws and regulations:

(a) Reviewing and amending existing sectoral legislation (e.g., in agriculture, energy, forestry, water, and transport) to explicitly incorporate climate change mitigation and adaptation objectives and measure.

(b) Developing sector-specific climate change regulations under the overarching framework of the EPA Act to address the unique challenges and opportunities within each sector.

(c) Ensuring coherence and avoiding conflicts between different sectoral policies and regulations related to climate change through a strong coordinating mechanism mandated by law.

The limited awareness and participation of local communities and other stakeholders in climate change decision-making processes can hinder the effectiveness and sustainability of mitigation and adaptation efforts.

A top-down approach may not adequately address the specific vulnerabilities and needs of local communities, nor leverage their valuable indigenous knowledge. The regulatory framework should promote inclusive and participatory approaches to climate action:

(a) Developing legal frameworks that support community-based adaptation initiatives and empower local communities to implement climate-resilient practices. This could involve providing legal recognition and support for community-led environmental management and resource governance.

Ghana’s ambition to participate effectively in international carbon markets is hampered by the current lack of a structured legal and regulatory framework governing such participation.

Key issues like the legal definition and ownership of carbon assets remain unaddressed in Ghanaian law. While At 1124 establishes the Carbon registry as well as the carbon market committee, the Act does not define what constitutes carbon assets. A comprehensive regulatory framework is needed to provide clarity and attract investment. The regulatory framework should establish the legal foundations for carbon markets:

(a) Enacting primary legislation that clearly defines carbon assets, establishes ownership rights, and outlines the legal framework for carbon. This could be a key component of future amendments to the EPA Act or a separate piece of legislation.

Furthermore, Ghana faces barriers to the widespread adoption of renewable energy technologies. These include not only financial constraints but also policy and regulatory gaps, as well as infrastructure limitations. While the government has articulated ambitions for renewable energy development, a supportive regulatory framework is crucial for accelerating this transition. This should involve:

(a) Implementing clear and stable legal frameworks and incentives (e.g., feed-in tariffs, tax exemptions) to attract investment in renewable energy projects.

(b) Streamlining permitting and licensing processes for renewable energy installations to reduce bureaucratic hurdle.

The prevalence of illegal activities such as illegal mining ("Galamsey") and logging significantly exacerbates environmental degradation and undermines climate change mitigation efforts, particularly in the forestry sector. These activities lead to deforestation, loss of carbon sinks, and pollution of water resources, directly hindering Ghana's ability to meet its climate commitments. A stronger regulatory framework with enhanced enforcement capacity and stricter penalties is essential to combat these illegal activities:

(a) Strengthening and strictly enforcing existing laws and regulations related to forestry and mining, with increased monitoring and surveillance to deter illegal activities.

(b) Reviewing and increasing penalties for illegal mining and logging offences to ensure they serve as effective deterrents.

(c) Developing legal frameworks that promote sustainable forest management and provide alternative livelihoods for communities dependent on forest resources, reducing the incentives for illegal logging.

Finally, resistance to adopting low-carbon practices, particularly in economically significant sectors like mining, presents a challenge. Mining companies may perceive the implementation of low-carbon policies as costly and uncertain. The regulatory framework needs to create incentives and provide clear pathways for low-carbon transitions in key industries:

Developing sector-specific regulations and guidelines for low-carbon practices, outlining clear emission reduction targets and pathways for compliance.

Providing financial and technical support to industries transitioning to low-carbon technologies, potentially through targeted tax breaks or subsidies.

Facilitating dialogue and collaboration between the government, industry stakeholders, and technology providers to identify and overcome barriers to low-carbon adoption.

The challenges outlined above are not isolated but rather interconnected and mutually reinforcing. The lack of adequate funding, for instance, limits the capacity for effective policy implementation, technology adoption, and enforcement.

Weak institutional coordination can lead to fragmented approaches, duplication of efforts, and inefficient resource allocation, further hindering progress. Data gaps undermine the ability to track progress, assess the effectiveness of interventions, and attract climate finance.

The absence of a strong legal mandate, until the recent EPA Act, created uncertainty and made it difficult to hold actors accountable for climate action. Addressing these multifaceted difficulties requires a holistic and integrated approach that strengthens the entire climate governance ecosystem in Ghana.

A robust and well-enforced regulatory framework is paramount for overcoming these challenges and achieving Ghana’s climate change mitigation and adaptation goals. The Environmental Protection Act, 2025 (Act 1124), provides a crucial foundation, but its effectiveness will depend on the development of clear and comprehensive regulations, their consistent enforcement, and their integration with other relevant sectoral laws. A strong regulatory framework can:

(a) Provide legal certainty and predictability for businesses and investors, encouraging investment in climate-friendly solutions.

(b) Establish clear mandates and responsibilities for government agencies and other stakeholders, fostering better coordination and accountability.

(c) Set standards and targets for emission reductions and adaptation measures, driving concrete action across sectors.

(d) Create incentives and disincentives to promote sustainable practices and discourage environmentally harmful activities.

(e) Facilitate access to climate finance by providing a credible and transparent framework for climate action.

(f) Empower local communities and other stakeholders to participate meaningfully in climate governance.

6. CONCLUSION

Ghana faces significant and complex challenges in its climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies, primarily stemming from inadequate funding, policy implementation gaps, limited technical capacity, weak institutional coordination, data deficiencies, and the historical reliance on a policy-based legal regime. The enactment of the Environmental Protection Act, 2025, offers a renewed opportunity to strengthen the legal framework for climate action.

However, sustained political will, the development of comprehensive and effectively enforced regulations, and a concerted effort to address the interconnected nature of these challenges will be crucial for Ghana to effectively navigate the pathways to mitigation and build resilience against the adverse impacts of climate change, while also capitalising on the opportunities presented by the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Continued focus on strengthening the regulatory framework in key areas such as climate finance, renewable energy, carbon markets, and enforcement will be essential for Ghana to achieve its national climate goals and contribute effectively to global climate action.