Despite the recent controversy surrounding the award of Ghana’s first lithium mining license to Atlantic Lithium, a company incorporated in Australia and listed on a submarket of the London Stock Exchange, the civil society movement (CSOs) in Ghana has been very restrained and constructive in their criticism of the deal.

In this author’s recent comment on the matter, for instance, very specific, reasonable, recommendations to Ghana’s Parliament were made to assist in the improvement of the agreement before it considered for ratification.

Some CSO demands as the lithium deal moves to Parliament

These recommendations include:

Changing the flat royalties provision in the agreement to a flat + variable royalty, whereby the 10% floor rate in the agreement is buffered by an extra, incremental, royalty layer once the operational margin crosses a certain threshold. In short, the more profitable the operation becomes, the more Ghana must earn.

Add “creative options” to the equity provision for the State such that once the economics of the project attain a certain trajectory, the State would have the right to exercise convertible securities and increase its ownership. In short, after the investors recoup their investment and make a good return, Ghana deserves additional say in the local company producing the lithium, Barari DV, plus higher dividends.

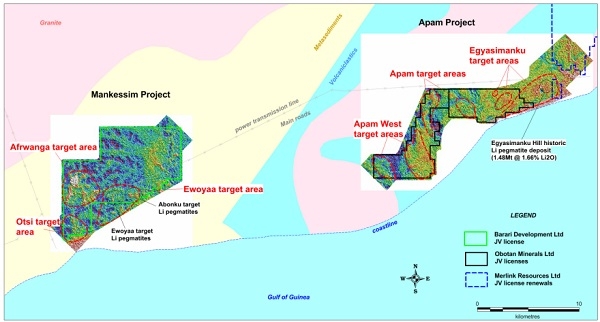

Addressing the state equity participation issue comprehensively is critical because the current project – Ewoyaa – is only a small fraction, just a little above 7%, of the total acreage licensed to the company directly or through affiliates to search for more lithium and other minerals, even as at least 50% of the lithium to be produced at Ewoyaa has already been committed to an American off-taker.

Instructively, 7 other deposits, besides the main Ewoyaa formation, are being primed for development and re-licensing by Ghana (and in some cases for further exploration work). Furthermore, the global horizon for lithium is highly complex and volatile, requiring clever positioning by the State to benefit from any upside and to minimise risks on the downside.

To ensure that the chemical refinery shall be prioritised, the provision in the agreement for a scoping study to be conducted to determine whether Atlantic Lithium shall indeed proceed to do so must be tightened to specify what exactly would be the yardstick of satisfaction Atlantic Lithium shall use to decide whether or not the refinery can be built. Doing this will allow easy and transparent monitoring of the process.

Since the interplay between economics and chemistry is much more complex for lithium than for, say, gold or bauxite, it has been suggested that the types of refining acceptable to the State should be specified in order to set clear expectations about the actual degree of value addition.

Ghana’s sovereign wealth fund (MIIF) is co-investing alongside the central government through various commercial transactions. Shareholding protections necessary to secure the public interest have not been disclosed. Instead, the public has been treated to a stream of self-congratulatory praise about phantom quantum gains. We have called for this perversion to be corrected.

The fiscal streams expected from the lithium license are not as the country has been told. Further disclosures of extra-contractual engagements between various state entities and the investor is required to determine the full facts. Likewise, planned equity participation must be designed to manage various risks.

The Government’s chief advisor is undermining trust

One would have thought that suggestions such as the above would have set the stage for a robust national conversation on what must happen between now and March 2024, when the government has promised to lay the lithium contract before Ghana’s Parliament. Unfortunately, the conduct of the chief advisor to the government on these matters, the Chief Executive of the Minerals Commission (CEO-MC), is undermining the atmosphere of trust for further constructive engagement.

His constant accusations of untruthfulness targeted at CSOs appear to be a deflecting tactic to prevent scrutiny of his own claims, and hint at the use of reverse psychology techniques to stop the exposure of untruths that have been infused through the press to obscure the urgent task of safeguarding Ghana’s lithium wealth.

In a recent series of exchanges between this author and the CEO-MC on a primetime television show on Ghana’s Joy TV, consistent attempts were made to turn every effort at shining light on the deal into a ping-pong of truth and lies.

Setting the records straight

This essay will attempt to straighten the records as conclusively as possible. Further essays may follow depending on the substance and tone of responses it receives.

Was there no data about lithium resources in Ghana until Atlantic Lithium?

Over and over again, Ghanaians have been told that the reason why no competitive process (such as auctions or tenders) was used to attract more interest in Ghana’s lithium was that there was a complete or serious unavailability of data.

Even when the point was made that the Ghanaian authorities have long been aware, since at least 1916, that the Cape Coast Birimian stratum (which extends west from Ghana into Ivory Coast and Guinea, and north into Burkina Faso and Mali) is rich in lithium, pro-government analysts insisted that this was merely “occurrence data” that could not have been relied upon for any enhanced marketing to support an auction of the blocks.

A picture has been painted that Ghana was this hapless place wholly bereft of knowledge of its own treasures, and that Atlantic Lithium was this flush-with-cash entity that came in, invested tens of millions of dollars, made discoveries, and is now, out of sheer mercy, handing over to Ghana some undue largesse.

Without mincing words, both claims are plain untruthful.

Atlantic Lithium has never hidden the fact that, in its previous incarnation as Ironridge Resources, it bought a concession that was well established as a lithium find, except that work was still outstanding to fully prove the reserves and certify them to an international standard (such as JORC).

Source: Atlantic Lithium (2017)

On page 11 of its 2017 annual report, it mentions clearly that the asset it bought was a “historical” find demonstrating resources of 1.48 million tonnes of 1.66% lithium oxide bearing ores (the same high grade as Manono, the world’s largest rock lithium find). What exactly was this “historical” find?

The Egyasimanku Hill discovery was made in the Yenku Forest Reserve in 1962 and set the tone for the prospectivity of lithium in the whole Apam – Mankessim area. Thus, in 1973, the “Ghana in Focus” segment of World Development, a journal (specifically volume 1, Issue 8), had this to say:

“The main lithium mineral in Ghana is spodumene (LiAISi2 06) which occurs in many pegmatite bodies, often in association with beryl (Be3 Al2Si6O18).”

The decision to make lithium one of Ghana’s main investment highlights in 1973 owes to the seminal work, “Geochemical aspects of spodumene pegmatites of the Saltpond area,” by Dr. Alexandra Amoako-Mensah, after whom the geology prize for females at the University of Ghana, Legon, is named. This is the same work that inspired Atlantic Lithium’s CEO, Vincent Mascolo and his sidekick, Len Kolff, to set off from Australia to strike their fortune on these shores.

Given that the suspicion of high-grade lithium in the Central Region of Ghana has always been very high, and that the country’s own geological service had already confirmed a find and estimated the resource extent as far back as 1962, it cannot be accurate to say that there was no data that could have served as a basis to run auctions for the prospecting leases. The real reason is simply that officialdom has decided for a long time that auctions are not how they will do business for whatever reason.

India’s decision to auction 20 blocks for exploration was not as a result of complete bankable data on proven reserves, based on international JORC certification. Many of those blocks only have suspected occurrences of lithium and similar minerals. India’s decision was strategic, based as it is on an intent to market widely, draw greater interest, boost massive investment, and therefore enhance the competitive negotiating position of the government.

The importance of broad marketing to attract as many investors as possible and boost the injection of resources, whilst enhancing competition, is vindicated by the history of Atlantic Lithium in Ghana, which shall be recounted shortly in this essay.

It also bears mentioning that in the September 2022 technical study conducted by Atlantic Lithium, and on which its initial mining lease application in October 2022 was based, a large proportion of inferred resources were included in the tally, compelling its strategic partner, Piedmont, to consider the effort as merely a scoping, rather than technical, study. This was well after the company had declared commerciality. There is therefore no basis in assuming the sort of data standards that pro-government analysts are propounding as a requirement for auctioning prospecting leases.

Did Atlantic Lithium spend vast amounts of money in Ghana?

In 2016, when Atlantic Lithium (Atlantic) started the process of acquiring the pre-mining leases held by local companies, Merlink and Obotan, which process eventually led them to the issued mining lease, it had been something of a resource-speculator for three years during which period it had attracted very little money.

In that year, Atlantic (then known as “IronRidge Resources”) made no income and declared a loss of $2.3 million, standard for an early-stage quasi-speculator. It had accumulated losses of $10.3 million and had net equity of just $15.6 million, down from $17.8 million in 2014. Virtually all the $10.7 million it still had in the bank had come from the ~$15 million it got from its 2015 listing on the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) of the London Stock Exchange (a kind of sub-division of the LSE where startups go to cut their teeth).

In fact, the year before listing, it had a grand total of $27,600 (TWENTY-SEVEN THOUSAND DOLLARS AND SIX HUNDRED DOLLARS) in the bank. The primary funders of the business at this stage were Assore, a company mostly associated with South African billionaires, Desmond Sacco and Patrice Motsepe; and Sumitomo, the Japanese chemical giant.

None of the information in the preceding paragraph is meant to diminish the entrepreneurial prowess of the founders of Atlantic. It is merely to dispel the myth that the financial capacity to acquire commercial data was so massive that Ghana had no choice than to grovel at Atlantic’s feet for crumbs.

On that same score, it is worth mentioning that Atlantic secured the money it used to develop the vaunted “data” being argued about by simply selling forward a portion of the lithium to be mined to Piedmont Lithium of Tennessee for $17 million. This transaction effectively valued the Ewoyaa project at roughly $175 million (the valuation is a moving target as development costs escalate and milestones are attained).

With roughly $87 million in funding commitments (and assurances to share cost overruns), Piedmont has secured 50% of the Eyowaa project. Meanwhile, MIIF, Ghana’s sovereign fund, is still haggling over an investment of $27.9 million for a comparatively puny 6% of the asset after missing the opportunity to invest early despite the historical data backing a very high suspicion of commercial lithium resources in the area. The question here is: what kind of strategic interactions go on among the Minerals Commission, the Geological Service, and Ghana’s money managers?

All the sums mentioned in this section pale in significance besides the fantastic amounts we have been hearing government agencies like the Bank of Ghana commit regularly to spending on swanky head-office buildings. The problem is cleanly and squarely a massive failure of imagination.

Did Ghana secure the most generous terms from Atlantic?

In the previous essay, we explored the issue of Ghana’s fiscal gains from the Atlantic deal at some length, but mostly in relation to the royalty and state equity aspects. In the interest of clarity, it is important to present a more succinct and, yet, rounded view.

Speaking to the country’s newspaper of record, the sector Minister was, as has been his style since he signed the lease in October 2023, fulsome in praise of his own handiwork. Not surprising as his tune is from the hymn sheet of his chief advisor, the CEO of the Minerals Commission, whose talking points have saturated the mainstream press with lavish doses of feel-goodness about a grand stream of benefits in the form of high royalties, juicy taxes, and the thrilling eventual participation of Ghana in 30% of the project’s equity.

Unfortunately, most observers who have fallen for this sugarcoating have been had. The government has not been sufficiently candid about the overall fiscal effects of the full deal it has engineered.

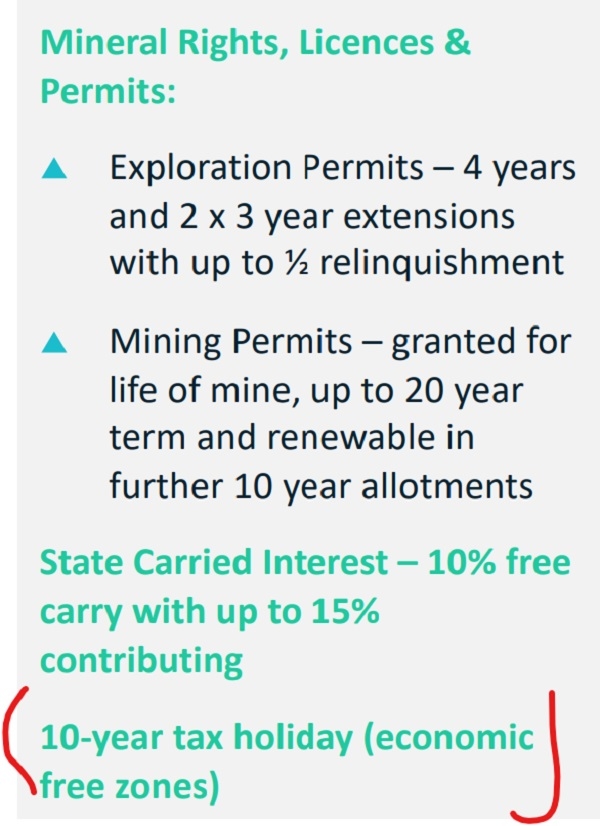

It has not, for instance, publicised the fact that Atlantic is getting a 10-year tax holiday due to a curious decision to have it benefit from the Ghana Free Zones regime, despite the tradition in this country of excluding primary economic actors, like mining companies, from this regime. This lack of transparency is shocking since Atlantic has been using this win as a major prop in all its engagements with investors (such as its investor presentation in November 2022, and at the Mining Indaba).

It has not educated the public about the bulk-electricity tariff that has been promised to Atlantic, which the company claims will save it between 30% to 50% of electricity costs, even though many industrial concerns in Ghana have been on waiting lists for years just to secure basic high-capacity meters.

The effects of such concessions, and any others not expressly spelt out in the agreement, but which may have been given through side arrangements, greatly affect the true size of the deal’s fiscal package. No doubt if analysts were more broadly aware of these tax and utility concessions, they would have been more restrained in their enthusiasm. Some analysts have even claimed that the state can expect to make between 50% and 60% of the project’s total returns. The truth, however, is that even after the expiration of the ten-year Free Zones concession, beneficiary companies continue to enjoy a low income tax regime of less than 10% (usually 8%).

Hence, if Atlantic’s claims of the free zones status are what they seem, then the State will likely find that its total take from the project will likely be far lower than is being widely advertised by pro-government analysts. More importantly, it completely discredits the attempts to paint the lithium deal as the best in the country since even companies like Newmont, whose stability agreements have been widely criticised for denying the State equity participation, do not enjoy such concessions.

Is Ghana on course to acquire 30% of the equity value?

The claim that the country is poised to secure 30% of the ownership of its lithium is wholly incompetent. It mixes up the freed carried interest, the paid interest in the Ewoyaa project alone, the ongoing discussions about extending the ownership in Ewoyaa to cover the consolidated holding structure in Ghana that will encompass all the different leases with prospective lithium and other mineral rights, and the potential ownership in the Australia-incorporated parent entity (which is actually IronRidge Resources, following the seeming disbandment of DGR Global). None of these rights and potential rights are additive by simple arithmetic. The only sure equity the state has negotiated is the 13% equity in Barari DV, the local leaseholder for Ewoyaa.

The ongoing effort by MIIF to close the transaction to acquire 6% equity in Barari, and 3% equity in the parent company, besides referring to two different equity structures, and therefore clearly non-additive, is further confronted by one other problem that MIIF has so far refused to clearly discuss: dilution.

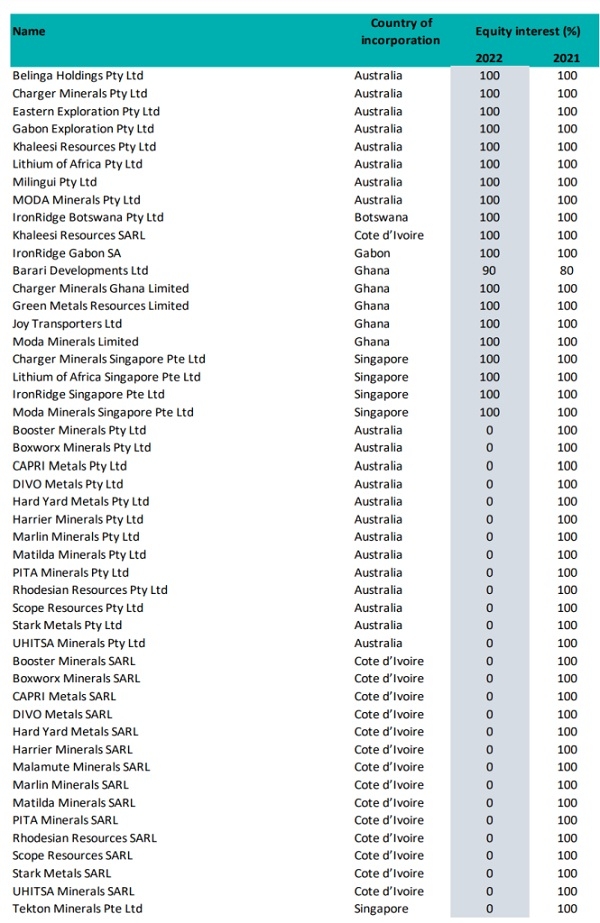

Because the various Atlantic Lithium affiliates, subsidiaries and parent are all early stage entities that have raised very little money so far, and are in the very early stages of projects across different mineral classes in many countries (from Chad and Gabon to Ivory Coast and Australia), it can be taken for granted that the bulk of fund-raising is ahead. The somewhat speculative intent behind some of the company’s pursuits can be discerned by just perusing the sheer list of affiliates.

Ghana is thus an early-stage investor in a company with its fingers in many unbaked pies. When some of those pies start to sizzle in the oven, large size issue offerings and placements are expected. Whilst the founders and senior insiders are protected by a fat suite of options, Ghana’s additional interest portions are exposed to heavy dilution.

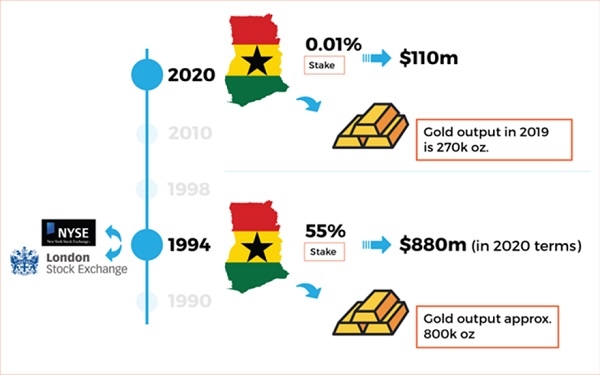

This is the same thing that happened to Ghana in the fabled story of Anglogold Ashanti, where the country’s equity went from 55% to 35% and then from 16.8% to 0.04% today. Dilution in the public markets is a brutal affair.

In short, it is disingenuous to talk about an assured 30% equity stake at this moment without disclosing the precise strategy to utilise the necessary convertible preference securities to prevent Ghana from being diluted to insignificance, and without explaining clearly to the public that the different Atlantic affiliate structures are not to be summed up linearly. There is no prospect of a 30% holding, simples.

Parliament must do its duty

In the wisdom of our much criticised constitution framers, the executive branch alone cannot award a fully functional mining lease. Parliament has a role to play. It would seem that Atlantic expects a breeze through Parliament from the project milestones roadmap below.

The parliamentary Opposition (minority party) has promised that the agreement shall not be rubber-stamped. So far, the government side has made no such commitment to the people of Ghana that they can expect diligence and rigour.

One can only hope that, for once, the entire Parliament will be united in rejecting the hallelujah chorus that many pro-government analysts are demanding we all join, open public hearings across the country, and eventually demand that the government incorporates all the valid inputs they receive into a final, significantly improved, agreement, whilst taking care to extract information about all extra-contractual concessions granted to Atlantic Lithium.

Perhaps, above all, Parliament should scrutinise any testimony or information given by the mercurial Chief Executive of the Minerals Commission with heightened vigilance.

Opinions of Wednesday, 31 January 2024

Columnist: Bright Simons

Abusing truth in Ghana's lithium deal

Entertainment