A National Unity Government For Ghana – Is It Time To Try Something Different?

Introduction

At a function to commence the official celebration of Ghana’s independence golden jubilee anniversary in January this year, the President, Mr. John Agyekum Kuffuor, reflected that as a young man in 1957, he had high hopes and aspirations for Ghana’s future. He implored Ghana’s youth to ensure that the next 50 years deliver progress and development that they can all be proud of (Ghanaweb, January 2007). Very few fellow Ghanaians will disagree that the last 50 years have indeed been a huge disappointment, as far the socio-economic development of our dear country is concerned.We will all do Ghana a great service, if as part of the golden jubilee anniversary celebrations, we reflected seriously on policies and measures that have worked, and those that have not served the country well. It is expected that through such honest and impassioned introspection, as a nation, we can collectively begin to put in place the foundation stone necessary for Ghana’s future prosperity.

I have written this article purely to start a genuine conversation, and I trust that my fellow compatriots will accept the arguments I made in the same spirit, and make their contributions accordingly.

Systems of government

Throughout our political history, we have experimented with two main systems of government: one party and multi-party parliamentary systems, excluding military dictatorships, which are not systems of government in terms of classical political science theory. Without doubt, one of the major benefits of the political party system of government is the discipline it imposes on its members, either in office or in opposition, to follow the official party line on policies and ideology.Some of the main disadvantages include the mentality of “winner takes all”, whereby the party in government seeks to maximize political advantage by giving out jobs and other political largesse to either members of the party, or individuals who are sympathetic to the government.

Another feature of the party political system is its over-reliance on loyalty to the exclusion of individual conscience. This can be both an advantage and a disadvantage. For example, in Australia, political parties, particularly the major ones i.e. Labor and Liberal, demand absolute loyalty to the policies of each party. Any member expressing a dissenting view on a party’s policy can expect to pay a heavy political and personal price. This can range from being discredited publicly by party colleagues through the media, or being passed over for promotion, or not being considered for frontbench positions. Indeed, members of parliament cannot exercise a personal conscience vote on an issue on the floor of the Parliament unless special permission has been granted for this to occur by the party leaders.

In general, multi-party systems of government work well in mature democracies, which have well-developed and established free market economies. In these systems, the differences in ideology between the major parties, which invariably alternate as the governments, can be very subtle indeed, to the extent that the general population hardly notices any dramatic changes in their socio-economic circumstances, irrespective of which party is in government. For example, in mature democracies such as the USA, the United Kingdom and Australia, any changes in policies resulting from a change of government is hardly earth-shattering. Any differences in policies tend to be on the margins. In general, the socially progressive governments (usually Labor governments) tend to focus on policies aimed at improving the socio-economic circumstances of the less privileged classes in society i.e. workers, the poor etc. On the other hand, conservative governments generally implement policies that are seen to favour the so called private sector.

Another important characteristic of mature democracies is that governments, irrespective of their ideological persuasion, tend to build on the legacies of their predecessors. In Ghana, since the overthrow of Kwame Nkrumah, successive governments have generally and actively dismantled any achievements of their predecessor. The result has been that, instead of moving forward and building on the progress made by the previous government, governments have tended to reinvent the wheel on many fronts. This has not only been wasteful in terms of resources, but has generally retarded progress.

Ghana’s current constitution

Ghana’s current constitution can be described as a hybrid, drawing on aspects of the British Westminster system, and the presidential system of the United States of America. To date, one of the endearing aspects of our nascent democracy has been that it has supported a seamless transfer of political power from one government (the NDC) to another (NPP). However, it is fundamentally a party-political system with some of the inherent inadequacies I have described above.A government of national unity for Ghana

It is time for Ghana to be bold, and not be a slave to political systems that in our present circumstances, may not offer maximum opportunity to use all of our available human resources and talents for the benefit of the country. I am therefore suggesting a system of government which preserves the best aspects of the multi-party system, but also requires the party in power to draw on Ghana’s available skills and talents into the machinery of government, where the main criteria for the appointment of individuals as ministers of state will be proven integrity, track record of performance and success, and the specific skills and experience the individuals bring to the machinery of executive government, rather than their political or tribal affiliation. Under the system I am advocating, four yearly elections will continue as they occur presently. The party with the majority of members of parliament will form government and control the legislative process i.e. formulation of laws. However, the appointment of ministers of state will not be controlled solely by the ruling party. An independent body of eminent citizens, the membership of which will be agreed by the parliament (both government and opposition members), will identify and select individuals who will be considered for ministerial appointment. The individuals to be considered for ministerial appointment can be drawn from industry (private sector), the public sector, academia and civil society, but will exclude members of parliament. They will go through the parliamentary vetting system for designated ministers, as occurs under the existing system.Each confirmed minister will have clearly defined outcomes that he or she will be expected to achieve in their portfolio. Their on-going appointment as a minister will depend on annual performance assessment undertaken collectively by the legislature (members of the ruling party and the opposition party sitting together as the national parliament) based on the key performance indicators (KPIs) for the agreed portfolio outcomes. Ministers can be reshuffled from one portfolio to the other, but persistent lack of performance, as well as proven cases of corruption and/or misconduct, will constitute the immutable basis for dismissal.

I believe that the system I am proposing, if it can be made to work, will usher Ghana into a new era of true accountability in government, where the party political system can no longer be used to protect and shield corrupt and incompetent ministers, as has happened over the past 50 years.

Separating the executive arm of government from the legislature, in the manner I am suggesting, will enable elected members of parliament to focus on their core responsibilities i.e. law-making and serving the needs of their constituencies. We should not forget that members of parliament are elected by their constituents, primarily to represent their interests. Some may argue that members of parliament who become ministers are better able to serve the interests of their constituents because of the influence they may wield within the ruling party. While this may be true, it often leads to pork barreling and an unfair distribution of national development projects. Assignment of national development projects must be based on “needs” rather than “political influence”.

A government of national unity as I have proposed in this article is not inconsistent with the principles of democracy. Ghana’s present constitution, as I understand it, allows for a limited number of non-elected individuals to be appointed as ministers of state, and in government, both the NDC and NPP have appointed one or two non-elected individuals as ministers. I am arguing for this practice to be expanded and fully entrenched as part of our system of government, so that as a nation, we can genuinely draw on the large pool of talent available both within and outside Ghana to manage the nation’s affairs. I believe that there are several well qualified and committed Ghanaians with great integrity, who may want to make a contribution to the nation through public office, but are deterred by the strictures of the current political party system.

Corruption in Ghana

Successive governments in Ghana have been ineffectual in addressing corruption and mismanagement among some ministers and party functionaries, partly out of blind loyalty to the individuals concerned, because of their party affiliations. Taking a firm action will not only be seen by party members as bringing disrepute to the party in the eyes of the public, but it may also be seen by party apparatchiks as disloyalty on the part of the leader. It may also be seen by party loyalists as undermining discipline, solidarity and cohesion within the party.Tribal politics

One of the unambiguous results of the party-political system in recent years in Ghana has been the re-emergence of tribal politics. In addition to helping to address corruption in government, a government of national unity, as described in this article, can assist in tackling tribal politics which is fully entrenched now in Ghana. The system I am advocating will require the government of the day to put the national interest first rather than the current situation where individual’s pursuit of wealth and appeasement of one’s tribal members is the order of the day.In Ghana’s political history, it can be argued that Kwame Nkrumah’s government was the only one which came close to forging some sort of a national unity in Ghana. His charisma and initial strong leadership encouraged a sense of national unity, where most citizens, I believe, considered themselves as Ghanaians first, and their tribal affiliations camesecond. Certainly, the tribal politics, which has been evident in Ghana since 1966, was less evident during Nkrumah’s regime. It could be argued that the one party political system he introduced helped during the early political history of Ghana, but through arbitrary detention and wanton stifling of legitimate opposition, he undermined the usefulness of a system which could have continued to foster national cohesiveness in Ghana.

Democracy and socio-economic development

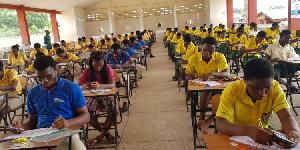

What is democracy? In my view, democracy is not only the freedom to choose the government of the day every four years, as it occurs presently in Ghana. I believe that it is about the freedom from abject poverty and economic deprivation. Democracy is also about systems of government that enable countries to continually achieve incremental socio-economic development. Fourteen years of democracy have done little to improve the socio-economic circumstances of the average Ghanaian.Some Ghanaians may disagree with me but the political maxim I subscribe to is: “give me first the economic kingdom and all others shall be added unto it.” It is undeniable that under the Kuffuor Government, Ghanaians have experienced more freedom of speech, and respect for human rights has increased much more than under the NDC government. But has this been enough? How about the socio-economic circumstances of the average Ghanaian? Have freedom of speech and enhanced respect for human rights been enough to stem the brain drain in Ghana? Many Ghanaians today are looking for opportunities to join the ranks of the ever increasing Diaspora, purely to improve their economic circumstances and that of their families, and not because of lack of freedom of speech, threats to their human rights, or concerns for their personal safety. And who can blame them? As human beings, we all aspire to certain basic minimum requirements for ourselves and our families. These are: adequate food, shelter, education for ourselves and our families, access to health facilities when we are ill, and the ability to provide the basic socio-economic needs of our families. After 50 years of independence, how many Ghanaians have truly achieved this within the country?

Take Singapore as an example, compared with more than 30 years ago; there is a lot more freedom of speech now. This has come about because, with a first world economy now, the government is not the only provider of jobs or “economic sustenance” for its people. When the government of a country is not the sole provider of jobs in an economy, it is no longer able to coerce its citizens or stifle opposing views. China and Vietnam, two of the economic power houses of Asia, still officially have communist governments. However, strong and continual economic development is leading to political changes, albeit at a slower pace than western governments expect, but it will surely come.

The status quo or a new governance paradigm?

It is totally unacceptable that, after 50 years of self-government, Ghana, with its suitable soils and climate for productive agriculture, abundant natural resources, entrepreneurs and human resources with a wide range of skills and experience, many of them excelling in international circles, cannot even feed its own people. Self-sufficiency in food production should be the first priority of any government that is committed to the socio-economic development of its people.Many things have not worked well for Ghana over the past 50 years. We have neglected basic infrastructure: roads, education, health, food production etc. We have misused our foreign reserves through corruption. Members of Parliament, including ministers and party functionaries, have ruled for themselves and the benefit of their immediate families and clans, rather than for the whole nation. We have become international beggars and still depend on the magnanimity of other countries, which through better management of their economies, are able to throw us crumbs in the form of foreign aid. We have squandered our heritage and that of future generations. Are we prepared to travel the same road for the next 50 years, or we are now prepared to hold our elected leaders truly accountable?

One option is to demand that a government of national unity, which traverses party political loyalties, and truly draws on the talents and skills of our citizens, no matter their party or ethnic affiliations, be established in 2008 to open a new page for Ghana.

I am the first to admit that the system I am advocating may not be perfect. However, we have very brilliant constitutional lawyers and political scientists in Ghana. Let us put their brilliant minds to work on a model of government that can draw on the ideas expressed through this article. In other words, let us truly start an international conversation, drawing on the Diaspora and our brothers and sisters in Ghana, on developing a new system of Government which will deliver the outcomes we expect, and which we can call our own: democracy, the Ghanaian way.