One essence of ecotourism is to preserve heritage while making sustainable income for host communities. The kente cloth is one traditional item worth preserving and Adanwomase is an important community whose livelihood revolves round the kente heritage.

I know some might be wondering: ‘Bonwire we know, but Adanwo..what?’ Adanwomase is one of two villages in the Ashanti Region that are home to historical weaving lineages appointed to weave for the Ashantehene. Adanwomase is about 17 miles from Kumasi. The other town, of course, is Bonwire.

According to oral tradition, an Ashantehene of a bygone era sent men from four villages (Bonwire, Adanwomase, Nsuta and Asotwe) to Bondoukou in present-day Cote d’Ivoire to learn how to weave. They came back and established the weaving tradition in their home communities. However, the traditional textile died out in two of the weaving communities, leaving Bonwire and Adanwomase.

Even in this equation, Adanwomase had been left out as the lesser known. To put it positively, Adanwomase is a well kept secret in today’s world of Asante kente. The town did not experience the tourist boom of recent decades enjoyed by its larger neighbour. Another reason is the influence of popular folklore. Remember the line in Ephraim Amu’s little song? Asante Bonwire kente me die menhunu be da o (My eyes have never beheld a wonder such as Asante Bonwire Kente).

Bonwire’s fame notwithstanding, kente produced by Adanwomase weavers remains of high quality as both traditional and modern designs are harnessed. Indeed, products from here maintain a more historical and cultural integrity. It must be noted that the Asantehene still commissions some cloths from Adanwomase,

Before one gets to this ecotourism destination one may stop at Ntonso, the homeland of adinkra cloth. Only about 12 miles from Kumasi, Ntoso is where all the necessary inputs for the traditional type of adinkra cloths are locally manufactured. This tourist destination is the biggest producer of adinkra in Ghana.

For those interested in adinkra designs, Ntonso has a new visitor centre and offers official guided tours. The walking tour allows visitors to see all aspects of adinkra production at close quarters. One can also try using hand ink stamps like the local craftsmen. If there is time, a quick stop at the Bobiri Forest & Butterfly Sanctuary nearby is not a bad bargain.

Adanwomase town itself is currently caught up in an interesting moment in history- suspended between its historical past and an imminent future of commercial expansion and tourism boom. The town has reason to be hopeful. You can feel it in the air as folks greet you: ‘akwaaba oo.’

But how this opportunity is used depends on how the fascinating textile history is researched and communicated. It also depends on how carefully the touristic expansion is handled. At present the Nature Conservation and Research Centre, an Accra based NGO is undertaking a study in the kente story.

While Bonwire has seven weaving families with a royal mandate to weave coloured kente for the Asantehene, Adanwomase has six, with the mandate to weave black and white kente (Mfufutoma) for the Asantehene.

The desire to learn more led to one of the last members of these lineages that grew up steeped in the old tradition. Nana Opanin Kwame Nsiah is a retired Mfufutomahene, the title for the chief weaver of the Asantehene’s black and white kente cloths.

Nana Nsiah estimates his age around 95 years. He grew up at a time when his family still received regular commissions from the Asantehene. Opanin Nsiah is so tradition-conscious that he would not even use the term ‘kente’ but calls the cloth by its original Akan name, Nwentoma which simply means ‘woven cloth.’

It was fascinating talking to the traditional textile aficionado. Nana Nsiah himself is from the Asene Abusua of the six lineages. Each of these families owns or used to own unique, royal collections of weaving samples known as sesia

The sesia baskets are crammed full of tiny cloth cuttings- kente samples that have been added to by successive generations of royal master weavers. In the past these designs were reserved exclusively for the Asantehene and the weaving of his cloths was shrouded in secrecy. Weavers working on the king’s cloths were only allowed to weave indoors.

It is unfashionable to have someone wear the same design as the king at a function. Nana Nsiah recounted how in 1961, one royal weaver of Adanwomase sold someone a cloth with a royal design (Fodua – ‘Tail of the colobus monkey’). The weaver was arrested at the durbar grounds where the person wore the design. The Asantehene thereafter refused to wear that design.

Today, many royal weaving lineages do not even have their ‘sesia’ collections anymore. With modernisation and the erosion of tradition, they are no longer valued: “When the old people die and the young ones take over, they don’t see the importance. They throw them away.” Nana Nsiah believes his family’s sesia basket to be the only one still intact in Adanwomase. He says his forefathers kept it in the same place as their family gods and thus the tiny antique of several years is still in perfect condition and full of kente samples.

It was fascinating hearing Nana Nsiah talk about the old royal weaving traditions: “In the old days when there was a commission, the king would provide lining cloth, pomade (body cream) and candles along with the order.” The lining cloth was placed underneath the new cloth as it was woven, to prevent it from getting dirty.

Calico is a cloth which is strongly associated with purity and is often worn by fetish priests. Thus this precaution was presumably aimed at protecting the cloth not only from physical soiling but also from contamination by impure spirits.

The pomade provided by the king along with the cloth was, in effect, an exhortation to cleanliness for the weaver. He was supposed to bath and anoint himself with it before sitting at the loom to work on the royal cloth. The candles were for waxing the yarn to make weaving smoother. Royal weavers would also weave a ‘pillowcase’ (a special bag) into which the new royal cloth was packaged before being presented to the king.

Nana Nsiah mentioned a special undergarment woven to be worn underneath the cloth. This garment known as danta was a kind of pair of shorts and was mostly woven with the warped stripe pattern called kyeme. There was an interesting explanation of the origins of this: “When the whites came they brought the undergarment 'danta' in that design. The king saw it and ordered it to be woven in silk. Now they use it as kente.”

There were also spiritual beliefs linked to kente weaving, most of which have died out due to modernity and Christianity - “These days nobody practises these things,” said one weaver. “It’s becoming a business now so there’s no time for that. And I am a pastor so how can I do those things?”

Weavers are expected to observe strict hygiene and cleanliness in and around the loom, in deference to its spiritual sanctity. They are not, for instance, supposed to pick anything out of their tool boxes with their left hand.

As the product of a sacred process, the kente cloth itself is traditionally imbued with sacred qualities. This applies in particular to the cloths woven for traditional leaders. According to one respondent, ‘Some kente cloths contained spirits in the old days but not now. ”

Although many of the old traditions have died out, Nana Nsiah still observes a few of them. His family’s sesia basket is kept in a special room inside a larger calabash that also contains some other relics of kente weaving history.

Nana Nsiah and his family members narrated some fascinating anecdotes in Adanwomase history. One related to the return of the Asantehene, Prempeh I to Ghana in 1924 after 27 years of exile mainly in the Seychelles where he was sent by the colonial British government. The Mfufutomahene at that time was Nana Amankwah, the maternal uncle of Nana Nsiah, who supposedly died in 1934 at a ripe old age.

“In those days sugar didn’t exist, only honey,” said Nana Nsiah, giving a sense of the time.

According to the story, upon his return to Ghana or the Gold Coast as it was then called, Prempeh I made a trip to Adanwomase to see his Mfufutomahene, Nana Amankwah. As a mark of honour, woven blankets were laid upon the ground for the king to walk upon. His visit lasted a few hours during which he commissioned three special cloths to mark his return to his homeland. These were the designs Ohene a foro hyen (The King has boarded a ship), Ekowoo menmu (Deer antlers) and Hyegya (Burning fire).

Another exciting moment in Adanwomase was when Nana Nsiah brought out a cloth that had actually belonged to Prempeh I. It was brought to him (Nana Nsiah) by the former Asantehene, the late Otumfuo Opoku Ware, to be copied. This cloth is called Akuabewu a name associated with the Akuaba fertility dolls carved in the village of Ehwia. The cloth is still in excellent condition though faded.

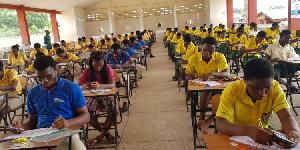

Evidently, kente has a rich history and an equally rich prospect. In a global village where cultures are crossing, the challenge is how Ghana is affecting the world with its brands of kente. At the level of production another issue is how it is being preserved particularly, among young ones. The youth are losing interest in picking up the kente vocation. As older weavers are dying away the implications of this trend become daunting.

Kofi Daniel Gyimah, from a younger generation of Nana Nsiah’s family, is a kente weaver and trader who to some extent, bridges the gap between the old and the new in Adanwomase. Fortunately, he has a good knowledge of the old traditions and of names of kente designs and has already made some efforts to catalogue old designs.

However, it is questionable how much of such knowledge will be passed on further and retained among future generations. To know more, make a trip to Adanwomase.

Entertainment of Thursday, 1 March 2012

Source: Kofi Akpabli