Ghana does not need to reinvent the wheel of development finance; it only needs to remember how the wheel was first greased.

In the 1970s, the National Investment Bank (NIB) made a decision that seemed quiet at the time but proved visionary: it moved beyond being a mere lender and became an owner. By taking an early equity stake in Nestlé Ghana, NIB planted a seed that would eventually save the bank. Decades later, when NIB faced the howling winds of financial instability, it did not collapse. It survived by liquidating a portion of those very shares it had acquired.

That wasn’t a bailout. It was the fruit of patient capital.

Today, the Ghana Export-Import (EXIM) Bank and the Development Bank face a similar crossroads. As the nation pivots toward a 24-Hour Economy, the banks confront a fundamental choice: Will they remain passive spectators collecting interest, or will they become partners in production?

The Debt Trap: Why Loans Alone Aren’t Enough

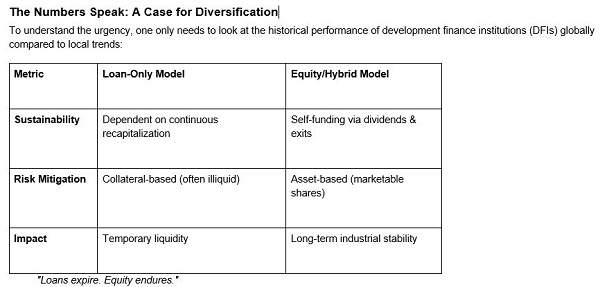

For too long, Ghana’s developmental model has relied on a “loan-only” approach. While credit is vital, it is often a heavy anchor for startup industries.

The Maturity Gap: Manufacturing and agro-processing—the backbones of the 24-hour vision—are capital-intensive. They require years to scale. High-interest debt often chokes these businesses before they ever reach a second shift, let alone a midnight one.

The Risk Mismatch: When a business fails, the bank loses its principal. When it succeeds wildly, the bank only collects interest. The “upside” of national growth remains trapped in private hands, while the “downside” risk stays on the public balance sheet.

The NIB Blueprint: Three Lessons for EXIM and Development Bank

The NIB–Nestlé success worked because it followed a logic modern finance often ignores:

Aligned Incentives: Ownership ties the banks’ success to the factory’s output, not just its ability to meet a monthly repayment deadline.

Institutional Shock Absorbers: Equity is a liquid asset. It builds a “war chest” that allows the bank to survive economic downturns without relying on taxpayer bailouts.

National Wealth Creation: Equity allows the state to retain a share of the value created by its interventions, ensuring that “national champions” remain, at least in part, national.

Fueling the 24-Hour Economy

The “24-Hour Economy” is more than a policy shift; it is an infrastructure challenge. To keep factories humming at 3:00 AM, you need more than a bank statement—you need guaranteed raw material supply chains, optimized logistics, and secured off-take agreements.

By taking strategic minority equity stakes, EXIM Bank and the Development Bank can transform from debt collectors into industrial architects. They can:

Directly fund raw materials: Ensuring processing plants never run out of maize or cocoa.

Exercise operational oversight: Using board representation to promote efficiency and transparency.

Crowd in capital: Signaling to private investors and the diaspora that the project is “de-risked” because the state has “skin in the game.”

Conclusion: From Banker to Builder

Development finance should not just be about recovering money; it should be about creating value that outlasts the person who signed the check.

NIB survived because it invested in real businesses and waited. EXIM Bank and the Development Bank now have the opportunity to do even more. By adopting an equity-led strategy, both banks can move from being lenders of last resort to builders of first-class industries.

A 24-Hour Economy cannot be sustained on short-term funding. Ghana has shown it can build titans before. It’s time to stop lending to the future and start owning it.

Business News of Friday, 13 February 2026

Source: Elikem Desewu, Contributor