Once an underdog in Africa’s quest to promote financial inclusion through digital financial services (DFS), Ghana is proving its doubters wrong and giving the oft-heralded East African markets a run for their money.

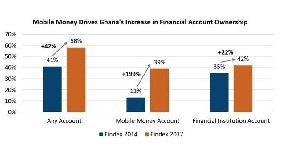

That’s the story that emerges from the 2017 Global Findex data, which show Ghana claiming its spot among the most successful and fastest growing mobile money markets in Sub-Saharan Africa.

In 2014 — the last year that Findex released data — just 13 percent of Ghanaian adults owned a mobile money account.

This figure paled in comparison to those of countries like Kenya (58 percent) and Tanzania (32 percent), leading many to believe that Ghana would never catch up to its peers. But the latest Findex numbers show that 39 percent of Ghanaian adults are now mobile money account owners — a three-fold increase that is prompting observers to wonder how Ghana mounted such a stunning comeback.

Early struggles

Ghana’s first mobile money deployments launched to much fanfare in 2009, but the excitement proved short-lived. After three years, only about 350,000 Ghanaians were actively using mobile money accounts.

To put that in perspective, Tanzania introduced mobile money only a year before Ghana and had about 8 million active accounts by the time Ghana reached 350,000.

Faced with these numbers, Ghana’s providers grew concerned that uptake would never reach the levels found in Kenya and Tanzania, where the introduction of mobile money led to rapid growth in account ownership and use.

As industry leaders and policy makers struggled to determine where they went wrong, they came to focus on the Bank of Ghana’s 2008 Branchless Banking Guidelines. They realized that despite the Bank’s good intentions and desire to promote a more inclusive financial services industry; these guidelines were creating obstacles for mobile money.

The biggest was that it restricted e-money issuance and agent recruitment to consortiums of at least three licensed banks. This resulted in a classic free rider problem, in which banks were discouraged from making investments that would benefit others in the consortium. It also left little incentive for mobile network operators (MNOs) to make crucial investments in launching new products or recruiting agents that were ultimately the property of the banks.

“There were complaints; there were frictions in the market place,” recalls Elly Ohene-Adu, head of banking services and payment systems oversight at the Bank of Ghana from 2010 to 2016, in a recently released CGAP publication that recounts Tanzania and Ghana’s pathways to DFS success.

Revised regulations spur provider investments

Recognizing the need to revisit the 2008 guidelines, Ohene-Adu and her colleagues worked with CGAP to engage the MNOs and banks in a dialogue around regulatory reform.

By 2013, the Bank of Ghana had begun drafting new regulations. After a contentious process that included significant pushback from some of the country’s largest banks, it released new agent and e-money guidelines that permitted MNOs to own and operate mobile money networks under the central bank’s supervision.

“This was what the telcos were waiting for. So, they just spread their wings,” Ohene-Adu explains.

In less than a year, MTN Ghana was aggressively investing in agent recruitment and customer education. This on-going effort has helped MTN amass 75 percent of the country’s active accounts. By 2017, Ghana had over 11 million active mobile money accounts, and an explosion of new use cases had made it possible for Ghanaians to do everything from open a savings account to purchase government treasury bills on their phones.

The regulatory reform process that began in 2013 seems to be largely responsible for the state of DFS in Ghana today because it gave MNOs the confidence to invest in new products and agents.

The future of digital financial services in Ghana

The fact that mobile money growth in Ghana has accelerated even as it has stalled in countries like Tanzania raises important questions about how far a country can get on smart regulations alone. Tanzania is often held up as a model for DFS supervision, owing to its early decision to take a test-and-learn approach to formulating regulations. But account ownership there increased by just 7 percentage points to 39 percent from 2014 to 2017. CGAP compares these two countries’ experiences in a new publication, finding that regulatory approach is just one of many components of DFS success. Other factors include providers’ commitment to investing, a competitive landscape of DFS providers, interconnected services and compelling use cases.

Whether Ghana will be able to replicate its success in the years to come is an open question, but the fundamentals remain promising. In 2015, CGAP argued that Ghana was, in some ways, the most “DFS-ready” country in Africa, with 92 percent of adults holding a form of ID required to open an account, 95 percent having basic numeracy, 91 percent owning a mobile phone and 74 percent already sending and receiving text messages. These statistics bode well for the ongoing adoption of mobile money.

This is especially true considering that the country’s DFS industry now includes not only mobile money providers but banks, FinTechs and others that are leveraging mobile money account ownership to offer customers a range of new use cases.

Of course, the past is not always prologue. The impact of Ghana’s transition to payments interoperability, implemented by the Bank of Ghana in May 2018, remains to be seen. Attempts to diversify customers’ use of DFS beyond person-to-person payments are on-going. AirtelTigo and Vodafone are looking for ways to chip away at MTN’s market share. And the emergence of FinTechs has led some to believe that mobile money may not own the future of DFS in Ghana.

Regardless of what lies ahead, Ghanaians are bullish on their country’s transition to a cash-lite future. And a new generation of innovators and entrepreneurs may hold the key.

“I see a lot of young Ghanaians who are really interested in making these payments work,” says Ohene-Adu. “I can see the passion and the drive there. They are like ‘How can I make this work better? I’m not happy with just sitting there and saying this is how we do things. How can we take this thing a step forward?’ So, the youth give me hope.”

Business News of Monday, 25 June 2018

Source: goldstreetbusiness.com