Opinions of Sunday, 30 December 2012

Columnist: Okoampa-Ahoofe, Kwame

The Road to Kigali – Part 17

By Kwame Okoampa-Ahoofe, Jr., Ph.D.

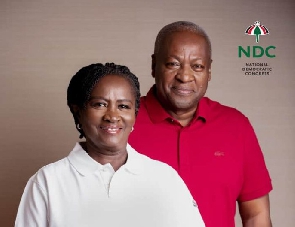

In this segment, I have decided to diverge a bit in order to briefly address the simmering issue of Northern Ghanaian fee-free education policy, on the books since 1957, and an issue that may well explode in the not-too-distant future into a national crisis, particularly in the wake of the “election” of a northern-descended Ghanaian premier who appears to be more ethnically self-interested vis-à-vis this sticky question than anything else. Indeed, in the heat of Campaign 2012, when Mr. John Dramani Mahama appeared to have finally caught on to the idea of a comprehensive national free-education policy, it was to moderately (actually “expediently” is the right adverb) call for the postponement of the implementation of any such policy until 2016, when he will be gunning up for a mandate renewal or reelection.

What I am trying to address here is a rather presumptuous and intemperate rejoinder captioned “Rejoinder: What is Good for Northerners is Equally Good for Southerners – Katakyie,” authored by Anamzoya Dunia and published by Modernghana.com several days ago. I have not bothered to read the original piece to which Mr. Dunia – and I am hereby assuming that the author is a man – has rejoined because I am fairly reasonably familiar with the salient contours of the debate and some general aspects of the national education question.

At any rate, what surprises me vis-à-vis the fee-free national education question is the near-total absence of the name of Dr. Joseph (Kwame Kyeretwie) Boakye-Danquah, the putative Doyen of Gold Coast and Ghanaian politics, and the man who spent a remarkable amount of his distinguished legislative career vehemently advocating for the fair and equitable treatment of the citizens and inhabitants of the erstwhile Northern Territories, as the present-day Northern, Upper-East and Upper-West regions used to be called. I suppose such egregious omission is the thankless price that pioneers have to pay, oftentimes, for being successful at their seminal endeavors. In sum, what I am hereby implying is the fact that Dr. Danquah has become a victim of his own success, a phenomenon which is typically ironic. We need to also quickly point out that as the de-facto founder of Ghana’s flagship academy, the University of Ghana, Dr. Danquah’s influence on the country’s education is without compare.

Now, I want Mr.Anamzoya Dunia to get one thing crystal clear; and it is the inescapable and incontrovertible fact that Western Colonialism was not a charitable enterprise. Consequently, the weird notion that the British Colonialists, on the eve of their auspicious departure, out of the profuse goodness of their hearts, earmarked a humongous educational funding resource for the exclusive benefit of northern Ghanaians, at the altruistic expense of Britain’s national coffers, is absolutely nothing short of the chimerical and outright preposterous. And so, perhaps, it bears teasing out, however briefly, the sociology of the political economy of Western colonial imperialism.

First of all, the endgame of British Colonialism was not to present a generous welfare check to the victims of such extortionate enterprise. Rather, the primary colonial objective was to immitigably exploit the subject of such ungodly enterprise to the maximum extent possible and fill both the private and national coffers of the home country, or the Crown, to the maximum extent possible. We must also highlight the fact that at its peak – or apogee – Ghana was the West-African breadbasket for the British colonial regime.

What the preceding means is that the British colonial enterprise in West Africa was for most of the first-half of the twentieth century funded by “economic surpluses” garnered almost exclusively from British economic activities in the former Gold Coast Colony, including the erstwhile Asante Federation and present-day Brong-Ahafo Region, which was an integral part of the Asante Federation. What the latter means is that such wealth was almost exclusively generated from Southern Ghana, or what is today the Akan-dominated five regions of Ghana, including the Greater-Accra Region which was an integral part of the present-day Eastern Region.

Interestingly, recently, while during a conversation with a 43-year-old Ghanaian woman from Accra, I pointed out that part of the reason for the present economic impoverishment of the Eastern Region was due to the fact of Accra having been the capital of the Eastern Region, in addition to being Ghana’s capital until 1967 – and officially until 1981 or thereabouts – Naa Akwele, aformer prison officer, pouted in utter disbelief.

At any rate, the idea that the wealth of Southern Ghana was either overwhelmingly or exclusively generated with the paid labor of Northern Ghanaians is unduly exaggerated. And even as I write, it is simply not the case. Likewise, Mr. Dunia grossly overstates the factual reality when he exuberantly claims that the massive drifting of educated southerners towards clerical jobs, both during the colonial era and in the postcolonial era, created a huge vacuum in the primary economic sector, largely in farming and mining, which was generously and predominantly filled by northerners.

We know the preceding to be patently false because even by 1957, when the country reasserted its sovereignty from England, the literacy rate for the entire country hovered well below 30-percent. Even in the Greater-Accra and Central regions, the most highly literate parts of the entire country, the literacy rate could not have been upwards of 30-percent. And so the notion that the predominant occupation of Southern Ghanaians, in the colonial era, was clerical or in the civil service does not gibe with documentary evidence. By 1966, I have been reliably informed, Nkrumah’s fee-free educational policy and all, the literacy rate for the entire country was a modest 43-percent.

What we know for a fact is that the greater percentage of cocoa-farm labor and mining labor came from outside of Ghana, largely from the Eastern and Northern parts of the West African sub-region. What I am unabashedly saying here is that the money allegedly deposited by the British colonial administration into the so-called Ghana Education Trust Fund for the exclusive benefit of northerners was primarily generated right here in Ghana – from Akwatia, Obuasi, Konongo, Tarkwa and other parts of the entire “Akanaland,” if you will, especially where the extractive production of cocoa and timber are concerned. In essence, what I am saying here is that the truth ought to be told without rancor or bitterness. And I would rather leave the immortalized Prof. Adu A. Boahen out of this debate, his remarkable and recognized contribution to this important subject notwithstanding.

*Kwame Okoampa-Ahoofe, Jr., Ph.D.

Department of English

Nassau Community College of SUNY

Garden City, New York

Dec. 26, 2012

###