Opinions of Saturday, 27 October 2012

Columnist: Gem, Richy

Rawlings’ Cross-Party Games or Lessons for Democracy?

Irrespective of what it is, the slightest move by Jerry Rawlings ricochets into a ripple effect. The controversy, of late, surrounding his cross-party manoeuvring is typical. ‘At best, it’s a succinct reminder that good women or men aren’t honoured in their own country’. But love him or not, as a statesman, the former president is ticking the right boxes. This time, hopefully, much of the intended good would be preserved for the programme of re-education that Ghana must undergo to make its democracy more meaningful to its citizens. But as this article submits, vilifying the messenger rather than the message, in Rawlings’ case, does not help.

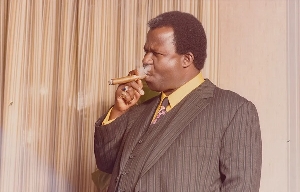

The settlement that Ghana now enjoys as a model for African democracy took great sacrifices. By the late 1970s, the consequences of colluding with distracters to unseat Kwame Nkrumah were all too evident. Such was the state of affairs that it called for something extraordinary. Rawlings rose to the challenge and in doing so infused the term ‘Junior Jesus’ into Ghana’s day-to-day language. Elsewhere, it restored hope in the Black Struggle after the euphoria that greeted the founding fathers’ declaration of independence entered those infamous dark days in the country. From thereon, the name ‘Rawlings’ ensconced itself onto Ghana’s political stage.

With two terms under his belt, Rawlings’ elevation to that of a statesman was deserved, inevitable and merited. And with this, if one cares to look, the shift to a more strategic posture. Rawlings, ardently, has been consistent with his views on governance, leadership and democracy. In wider circles, these stand out in the category of ‘must-read’ when it comes to Africa. The fact that he campaigned hard for National Democratic Congress (NDC) in 2008 is not denied. On account of the injustices meted out to this point, Ghana could not afford the descent onto the road of ‘dirty and divisive politics’. The result was Atta Mills’ alternative maxim of being a ‘president for all’.

Aspects of Ghana’s democracy, without knocking the great strides, are still underdeveloped. The ‘winner-takes-all, all-die-be-die’ and abusive claptrap, for example, is an affront to the country’s potential. More important, talk of peaceful elections is mere words without people to lead the ‘walk’. This means a break from convention in order to exert influence on all sides of the fence. ‘Surely, Ghanaians haven’t forgotten the collaboration and co-operation pledged by all sides on Mills’ passing? Likewise, it must be remembered that Ghana’s democracy does not just sit in an abstract vacuum when it comes to resolving Africa’s problems.

Rawlings, as a statesman, has shown that the cycle can be broken. His reference to the NDC as a ‘sister party’, for example, before the rank and file of the National Democratic Party (NDP) stood out despite what made it onto the headlines. Rawlings, by testing the waters, is insistent that all parties, not just those mentioned, owe it to the populous to exact probity, accountability and transparency. It is mischief-making to interpret these as anything else or games when differences and constructive criticism are integral to the resolve of political organisation. Democracy and truth-telling, just like freedom and justice do not leave margins for error when it comes to wrongdoing.

As things stand, Rawlings’ invectives of ‘greedy bastards’, ‘babies with sharp teeth’ and so forth lend themselves as a universal message to invigorate Ghana’s political landscape with a better agenda for all in mind. ‘Again in criticising Mills under the pretext that he wasn’t prepared to stand by whilst a good man’s led astray, he differentiates between the wisdom in a statesman’s craft and that of a die-hard partisan. Democracy, being a people-centred edifice, challenges Ghanaians to consider these metaphors carefully as a yardstick for lessons to deepen the process so that it works more for them.

About the Writer

The writer is an educationalist, development strategist and consultant, particularly known for his work in the areas of community development. Richmond, an advocator of racial justice, has operated at all levels. He is an accomplished and published writer, with articles in the Voice, Pride Magazine and The Northern Journal, notwithstanding his contribution in the book Black Families in Britain as the Site of Struggle, published by Manchester University Press. In June 2005 Richmond, assisted by a group of friends won a landmark ‘race’ discrimination case against Serco. He sports post-graduate qualifications in management and teaching including an MBA from the Bradford School of Management and also enjoys a successful career in the music business.