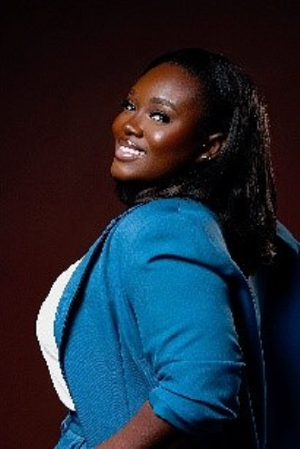

Monique Maddy tried and failed to launch a telephone service in Africa. She's moving on. Africa isn't.

Three short years ago, Monique Maddy was boasting that her company was going to "change people's lives" and "revolutionize things." Adesemi, the wireless pay-phone company she founded in 1993, had raised $37 million dollars, built a network in Tanzania, and moved into Ghana, and was planning to expand its service to the Ivory Coast. Maddy was the new face of African business. A Wall Street Journal article in September 1998 even proclaimed, "If the disenfranchised of Africa ever join the global economy, it won't be diplomats, politicians, or church people leading the way. It will be entrepreneurs like Monique Maddy."

It hasn't turned out that way. Maddy walked away from her company in disgust in the fall of '99. Her story is a familiar one, full of the government corruption that has become an African clichi, but the 39-year-old Maddy doesn't blame her company's demise on the bribery requests or Kafkaesque red tape. For the Liberian native, who's writing a book about third-world entrepreneurship to be published by HarperCollins next year, the real reason for Adesemi's failure and Africa's continental mire can be traced to the international development agencies that are designed to help the region. "Africa is worse off today -- in many countries -- than it was at independence, even though billions and billions have been spent," says Maddy, who herself served for five years as a United Nations Development Program officer. "As long as you have these kinds of institutions, you won't have any change."

Take Maddy's experience getting a pay-phone license. In mid-1995, a year after the Tanzanian national phone company granted Adesemi the license (and Adesemi had spent $1.5 million on its network), the phone company president said that it was no good because Adesemi's pay phones were wireless. Only after an acquaintance at the Harvard Business School, her alma mater, put her in touch with World Bank president James Wolfensohn did the matter get settled. The World Bank pushed the government just so far, however. The phone company insisted on charging Adesemi inflated rates to use its infrastructure. "When we asked the World Bank to do something about the rates, they said they couldn't tell the government what to do -- but they could lend them millions of dollars," says Maddy, referring to a $75 million interest-free loan the World Bank made to the national phone company. "They had a conflict of interest," she says.

Still, Adesemi kept at it, eventually building its network up to 600 pay phones and a pager service with 5,000 customers. The sell was easy, Maddy says, because Adesemi's phones actually functioned (the street nickname for the system was "the phones that work," she says).

When an Adesemi backer, CDC Capital Partners, refused to invest more money for the company's expansion into what Maddy argued were more profitable markets -- it wanted to see profitability in Tanzania first, despite the stacked odds -- she finally gave up. Maddy, who now lives in Boston, hasn't been to Tanzania since; her investors are selling off the network.

Not surprisingly, Maddy says her book will call for a radical departure from a system based on an international aid bureaucracy. "You basically have bureaucrats trying to develop countries," she says. "How many bureaucrats started Microsoft?"

Business News of Monday, 1 October 2001

Source: Ian Mount