- Home - News

- TWI News | TV

- Polls

- Year In Review

- News Archive

- Crime & Punishment

- Politics

- Regional

- Editorial

- Health

- Ghanaians Abroad

- Tabloid

- Africa

- Religion

- Election 2020

- Coronavirus

- News Videos | TV

- Photo Archives

- News Headlines

- Press Release

Business News of Saturday, 25 April 2009

Source: — Guardian News & Media

What Wall Street did to Ghana

In the leafy shade of the tree at the heart of Mangoase village, 50 women sat fanning themselves with their pass books, feeding babies, waiting their turn. Each approached the table to add the equivalent of a dollar or two to their savings or to pay back a small loan that had launched life-changing businesses.

One woman had borrowed to buy fish to smoke and sell on, one had bought beans and cassava to sell by the road side, another was building a small bar, a few breeze blocks at a time. This credit union deals in micro-sums for micro-businesses, but enough to send a child to school, buy a school uniform or exercise books.

In the next village, credit union money was kept in a green tin with three keys held by the women trained to run the accounts. Trust was their true key: these unions never had a loan default. This is banking, but not as the disgraced former boss of the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), Sir Fred Goodwin, knows it. The day that the British minister, Harriet Harman, was visiting these women’s credit unions, set up by Plan UK, Goldman Sachs bankers were thumbing their nose at the world by paying themselves 33% pay increases, as if their bonus culture had never brought down global banking. Their crash reaches right here, hitting these women too in soaring prices and threatened social cuts.

This is a good place to survey what Wall Street and the City of London did to the world. Ghana, which has met its millennium goals on children in primary education and cutting poverty, has been an economic and political success story, with high growth. A centre-left government has just taken over after hard-fought but peaceful elections. It is better protected than some, the prices of its gold and cocoa holding up in the recession. Offshore oil will flow in a few years.

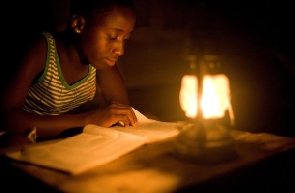

But last year world food and oil prices soared. China’s slashed demand for raw materials is harming much of Africa. Global warming caused a drought that drained the dam powering Ghana’s electricity, requiring crippling oil imports. The last government borrowed to cover these unexpected costs, the currency dropped in value, inflation rose to 20% and credit has dried up.

Economists at the NGO Oxfam point out that this was not caused by profligacy, but by external events last year. A further source of bitterness: if rich countries had kept their 2005 Gleneagles promises, as Britain did, Ghana would have received $1bn, with no need to borrow at all.

Where should Ghana turn? To the IMF, of course, now the G20 has swelled its treasury. But there is deep political and public resistance after previous bad experience. Remember how humiliated Britain felt going cap in hand to the fund in 1976. Ghanaians know how World Bank and IMF largesse came with neoliberal quack remedies.

Cutting public services, making the poor poorer, putting cash crops and trade before welfare was the old IMF way. It was the IMF that insisted on meters for Ghana’s water supply, demanding full cash recovery for the service, steeply raising costs for the poorest. The World Bank insisted on a private insurance model for Ghana’s health service that has been administratively expensive and wasteful. The new government rejects it, promising free healthcare for children. The IMF wants subsidies for electricity removed, again hitting the poorest hardest. A market policy of making individuals pay full cost for vital services instead of general taxation has made the IMF hated; Ghana has now voted for more social democratic solutions. Freedom from the IMF feels like a second freedom from colonialism to many countries.

No wonder the new government hesitates to apply for a loan, even though advisers warn them to hurry while the money lasts: big bids are in already from Mexico, Ukraine and others. Not much of the new cash is earmarked to protect developing countries from the global storm. Most will go to countries, like those of eastern Europe, that are seen as a threat to the global economy, to prevent more bank crises.

“The old Washington consensus is over,” Gordon Brown announced at the end of the G20. But that ideological battle is still to be fought out over developing countries’ economic policies. Surely what’s good for us is good for them? Economists wait to see if the IMF and the World Bank really represent “the new world order”. Joseph Stiglitz is not the only one to doubt a transformation in these old free-market tigers. Just watch them at the moment, forcing 40% spending cuts on Latvia and others.

The IMF protests that it has changed: it no longer prescribes or monitors so oppressively, and countries seeking loans can set their own goals. A British cabinet minister was quoted on G20 day as saying that it should be no more stigmatising than “going to a spa to recuperate”. Arnold Mcintyre, the IMF’s representative in Ghana, insists that it would be entirely up to the government to propose its own measures. This is, to put it politely, disingenuous.

Every government knows what it has to do to get credit, so Ghana has already said it will lower its deficit from 15% to 9.5% of GDP in one year, steeply cutting public sector costs. “They can do it through efficiency savings, with no damage to services,” says Mcintyre breezily. The government grits its teeth and says it can, and will: IMF economic thought often enters the soul of finance ministers. IMF power makes it the sole credit-rating agency for all other donors and lenders - an IMF thumbs-down means money from everywhere is cut off.

Oxfam’s senior policy adviser and economist, Max Lawson, doubts such cuts are needed, just a loan to tide Ghana over. “The IMF is too brutal ... demanding balanced books within one or two years. The only way to make such a deep cut is in social spending: teachers’ salaries are the main item.”

It’s a strange irony that Barack Obama and Gordon Brown embrace a Keynesian fiscal stimulus and in its name pour out global largesse to the IMF to distribute. But loan recipients risk a Friedmanite tourniquet, cutting off their economic lifeblood. Will Obama and Brown see how their policy is translated on the ground?

In Mangoase Harriet Harman looked at what can be done with small sums, especially in the hands of women using them for their children. She talked of how social progress is economic progress. Even minute social security payments advance local economies. That green bank box with its three keys is a greater multiplier of real growth than anything RBS or Goldman Sachs did.