- Home - News

- TWI News | TV

- Polls

- Year In Review

- News Archive

- Crime & Punishment

- Politics

- Regional

- Editorial

- Health

- Ghanaians Abroad

- Tabloid

- Africa

- Religion

- Election 2020

- Coronavirus

- News Videos | TV

- Photo Archives

- News Headlines

- Press Release

Opinions of Wednesday, 27 August 2008

Columnist: Doyle, Alister

Ghana elephants show U.N. deforestation headache

By Alister Doyle, Environment Correspondent

AFIASO, Ghana, Aug 26 (Reuters) - Rising elephant numbers in a protected forest park in Ghana are angering farmers whose crops are being raided in an unwanted side-effect of a plan to slow deforestation.

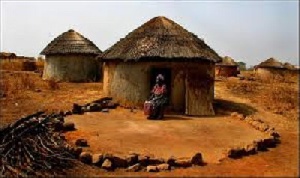

Locals in Afiaso, a village of 620 people in southern Ghana with no electricity nor running water, grumble that they are seeing limited benefits from agreeing to cooperate in protecting Kakum National Park forest, which starts 2 km (1 mile) away.

"We used to cut down a lot of trees to plant cocoa. Cutting down trees used to be normal," chief Nana Opare Ababio, 47, told reporters sitting with the village elders as children danced and banged drums alongside. On racks, cocoa beans dried in the sun.

Now, he said, villagers were respecting the park boundary.

"Money has not flowed to the village," he said, despite cooperation in helping protect the forest and a 2006 law meant to give local communities a share of park income such as from limited logging that does not damage the forest.

Finding new ways to slow the felling of the world's forests is a focus of 160-nation U.N. climate talks being held in Accra, about 200 km (125 miles) to the east. Deforestation accounts for almost 20 percent of greenhouse gas emissions.

But Afiaso may show some of the difficulties -- such as ensuring that money reaches poor local communities who are the ones slowing deforestation and dependent on farming maize, cocoa, plantains and cassava.

And in Afiaso there are the elephants.

"Elephants come to raid our crops. Then we have to buy food elsewhere," complained one man at a village meeting.

ELEPHANT RAIDS

Protected in the park, elephant numbers in Kakum rose to 206 in the last census in 2006 from 189 in 2000, according to Daniel Ewur, the park manager. The animals break out of their forest stronghold and eat crops.

Still, cooperation with the park has brought jobs for some people in the village and locals believe re-growth of forests in the protected area in recent years has helped stabilise once unpredictable rains and benefited crops, Ababio said.

And local children will grow up seeing animals that might otherwise have been driven to extinction, even though some complain the deal has cut hunting rights. The forest is home to rare species including the Diana monkey and the bongo antelope.

This shows the complexity of working out how to slow deforestation, said Emily Brickell, forests campaigner for the WWF environmental group after visiting Afiaso.

A new global deal to safeguard forests could cost between $20 and $30 billion a year, she said. In Afiaso, villagers said their priorities for any cash were a bungalow for a teacher or a new clinic.

"There seemed to be a lot of will and support for the idea that the communities should be receiving benefits," Brickell said of talks between park officials and villagers in Afiaso.

At the U.N. meeting, cash to slow deforestation is seen as a way to get many developing nations to do more to slow climate change that could aggravate water and food shortages through heatwaves, droughts, floods and rising sea levels.

Worldwide, the annual net loss of forest area between 2000 and 2005 was 7.3 million hectares a year -- an area about the size of Sierra Leone or Panama -- according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization.

Trees soak up carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas, as they grow and release it when they burn or rot. Slowing slash and burn policies by many farmers to clear land for crops would protect the climate.

AMAZON

At the talks in Accra, many delegations have stressed that local communities and indigenous peoples should benefit, from the Amazon to the Congo.

"There is an overall understanding that (aiding local people) is an important part of what we should do," said Luiz Figueiredo Machado, a Brazilian diplomat who chairs a group at the talks looking at ways to fight deforestation.

And in Afiaso, part of the answer may be pepper.

"We learnt from experts in Zambia that elephants don't like pepper," said park manager Ewur.Farmers were now mixing pepper with grease and then smearing it on rags that are hung from nylon ropes around fields with crops.

"Elephants have a very good sense of smell and stay away from the pepper. I've tried it myself -- it was 100 percent successful," he said. (Editing by Giles Elgood)